|

| Avram Finkelstein |

Even in the earliest moments of AIDS, and from deep within its swirling vortex, the outlines of its cultural meaning were detectable. Playing out as it did in the public sphere, it was impossible to overlook. So assumptions about it formed quickly in our shared spaces, and almost as immediately, they began to crystallize into canon.

All these years later, a new canon is rising. After decades of shell-shocked contemplation, those who were there are finally able to speak about it. A growing number of documentaries and gallery exhibitions have already been devoted to the topic, and these are just the first to the gate. There are major projects in the pipeline.

Why now? In cultural terms, we’ve been told it’s because of two corresponding anniversaries, the 30th anniversary of AIDS and the 25th anniversary of the AIDS activist coalition, ACT UP, the resistance movement that helped foreground the crisis in the American mind. But what does it mean that the 30th anniversary is a marker of the first New York Times article about AIDS, not the New York Native story that preceded it, or a 25th anniversary that overlooks the fact that ACT UP came well after the Denver Principles were forged?

It means that history is a process of generalization, an elevator pitch, and we privilege the stories that are easier to tell. In the public sphere, complexities are frequently slipped under the shadows of our zeitgeists, and well-worn media tropes supplant more disorderly truths.

How To Survive a Plague tells a tidy and heroic story of a group of treatment activists who came out of ACT UP and went on to help redirect the course of AIDS research. It’s a tale of empowerment, but it’s a telling which is incomplete, if not myopic. Slowly but surely, as their critiques became institutionalized, these activists were given a seat at the table. As to who profited more from the alliance, you will have to decide for yourself. Plague evades the intricacies of this particular contingency.

The stage for this eventuality was set by the ferociousness of ACT UP, which strategically wielded its might as outsiders. United in Anger takes a stab at this larger, messier and more diverse story, one that resists corralling. As films go, it has moments of aptness on this account, but its sprawl is at times impenetrable, and it is decidedly unpretty.

To be sure, telling the story of the community’s response to AIDS is challenging in ninety minutes. Still, How To Survive a Plague is a concise juggernaut, which appears to be barreling its way to the Oscars, and United in Anger has a foothold in academia, a community with an appetite for complexity. Combined, they might be a useful beginning towards constructing a history of this moment, one of the most compelling social movements of the late-twentieth century. But what about those who will only see one of them, or are being exposed to this material for the first time?

As an object lesson in what happens when historiography goes awry, consider the inaccuracies in the canon that have been allowed to ossify surrounding the image most cited when encapsulating the cultural production that came out of New York at that time, the shot heard around the world, the Silence = Death poster.

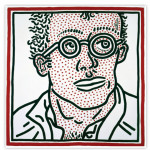

You’re likely to have heard of Gran Fury, one of the art collectives to come out of ACT UP. Within academic circles the work of this collective is an established part of our cultural history. It has been included in most of the major exhibitions and books on the topic and is in the permanent collections of MoMA, the New Museum and the Whitney.

You’re probably less familiar with The Silence = Death Project, a small collective that predated Gran Fury. In fact, it predated ACT UP. This is the collective that designed the Silence = Death poster. The work is generally misattributed to Gran Fury, even though this image was produced in 1986, over a year before Gran Fury formed as a spin-off of an ACT UP installation in the New Museum window. Considering this image is commonly used as a symbol of agency within academia, conflation of authorship can only be attributed to poor research or generality.

Other than siding with veracity, why would this distinction matter? If the study of social history is to be useful, there is at least one simple reason. Silence = Death was designed by six individuals who felt alone, but raised their voices anyway and discovered they were surrounded by a community. Gran Fury came out of this community and was anointed spokesperson by an institutional framework hungering for a voice on this issue. Future generations might find it helpful to know that while communal responses have exceptional potency, power also resides with individuals.

It might also be constructive to understand that what is freely referred to as the ACT UP logo, Silence = Death, was not actually designed for, or by ACT UP, and was never intended as a logo. It was a consciousness-raising project devised by a tiny political collective before the fact. But that is a tough pitch to an editor. So this image was framed as a logo by the major media outlets, compacting the fuller dimensions of the story. This gesture also folded ACT UP into the institutional framework it was critiquing, set up the defanging of its dissent and tacitly attributed ACT UP’s efficacy to branding, which is certainly untrue. In the case of AIDS, agency existed without any marketing at all. People were dying.

Additionally, the word logo also intones ownership. The Silence = Death collective set up their work product to be open source. Having been advised by an attorney to copyright the image before someone else did, potentially barring ACT UP from using it, they did, but never prevented any use of it, not even by an anti-abortion group that appropriated it. The collective adhered to the institutional parameters of intellectual property so that they might stand outside of it. They copyrighted it in order to give it away.

From its inception, the AIDS activist movement triggered public conversations that were the preamble to its own historicization. In spite of the imprecision, the cannon surrounding the cultural production of The Silence = Death Project and Gran Fury has fully gelled. It remains to be seen how United and Plague will stack up historically. Still, it’s likely we’re now witnessing the solidification of the history of AIDS. It would be bad if it were an incomplete one.

History matters. In fact, it’s all we have. So the canon we construct around AIDS in America is a generational responsibility, to say the least. Which raises the following question about these two documentaries as each hovers around institutionalization. After those who were there are gone, what is the story we will hear about them?

Avram Finkelstein is a member of the Gran Fury collective and The Silence = Death Project. This article was originally published on Artwrit.

1 Comment

1 Comment