The work of the iconic artist Keith Haring was featured in more than 100 solo and group exhibitions worldwide before he died of AIDS-related complications on February 16, 1990. Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, a new biography by Brad Gooch, traces Haring’s path from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, to New York City, where his graffiti-inspired art made him a darling of the downtown art scene and catapulted him to global fame. In the following excerpt, Haring, who often used his art to advocate for social change, agrees to go public as a person living with HIV in a fundraising letter for the AIDS activist group ACT UP. Please go here in this issue for a Q & A with Gooch.

Returning to New York City by the late summer of 1989, and feeling frustrated with the lack of response to any of his medical treatments, Keith had found his way to Dr. Paul Bellman, an internist affiliated with St. Vincent’s Hospital. Just a year older than Haring, and with many artists and writers among his patients, Dr. Bellman was considered, within the gay community, one of the more sympathetic, open-minded, and knowledgeable physicians with a large AIDS practice. His office manner was calm and cool, and he shared the latest scientific research while operating from a core belief that “HIV/AIDS was a race for survival rather than a death sentence.”

“Radiant, The Life and Line of Keith Haring”Courtesy of Keith Haring Foundation

“Shortly after Keith finally came to me, his T cells dwindled to less than twenty, which was very low, and he was getting new KS [Kaposi sarcoma] lesions,” Dr. Bellman says. “He had already been given a course of AZT that was not doing much and was making him anemic. That was no one’s fault. It was the reality of the situation. Monotherapy—with one agent—created resistance within four or five months, and you had the added toxicity of the drug.”

They resolved to cut Haring’s AZT dosage in half, and Keith began taking the experimental antiviral drug ddI, or didanosine, as part of a special program to fast-track drugs of promise to AIDS patients prior to FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approval. In September, he was injecting himself daily with alpha interferon, though, says Bellman, “the drug didn’t particularly work for him.” More successful was a treatment with Bactrim, to ward off pneumocystis pneumonia, also identified as “wasting syndrome.” The waiting rooms of AIDS doctors were packed during those years, and Keith was regularly at Dr. Bellman’s office in the West Village.

“Keith had an incredibly positive attitude relative to most of my patients,” Bellman says. “He was realistic. He wasn’t in the clouds about it. He wanted whatever medical treatment was available that could help him. But he somehow had a resilience that enabled him to do his art, and his life, and to have that kind of radiant energy, for want of a better word, which he uniquely possessed. He would come into the waiting room, and it wasn’t because he was Keith Haring, the famous artist, it was just his energy that affected everyone.”

top: “Silence = Death”, 1988; bottom: “Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death,” 1989Courtesy of Keith Haring Foundation

Haring was also, slowly, and with some hesitation, beginning to put his fame, body, art, and money at the service of ACT UP, a militant commitment that focused his activist energies and fired his public art for the rest of the year and into 1990. ACT UP had come to life in March 1987, when Nora Ephron asked Larry Kramer to take her place when she needed to cancel a talk at the Gay and Lesbian Community Center. In his speech that night, Kramer channeled all the prophet’s fury that had inspired the founding of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in his apartment in 1982 and his alarming siren of an article in the New York Native, “1,112 and Counting.” A woman in the audience that night was said to have stood up and shouted, “Act up! Fight back! Fight AIDS!” Two nights later, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power was officially formed to bring the battle for affordable treatments and a cure to targeted government agencies and pharmaceutical companies.

The only way to deal with something negative is to change it, turn it into positive action.

–Keith Haring

In its first action, ACT UP protestors blocked traffic on Wall Street and hung in effigy at Trinity Church the director of the Food and Drug Administration. By 1989, ACT UP’s weekly three- or four-hour Monday evening meetings at the Center had become fully realized, strident gatherings of hundreds of young men and women, loosely held together by Robert’s Rules of Order and by meeting moderators, each with their distinctive style. The revolutionary, “out” energy could be sexy and cruise-y, and though the meetings and demonstrations were far more diverse, young men in their twenties, in T-shirts, jeans, and Doc Martens, were, Kramer said, the “face of ACT UP”—all of them bound up by grief, anger, and a struggle to survive.

In the months following his diagnosis, Keith had continued not telling anyone except Gil [Vazquez], Juan Rivera, and Julia [Gruen]. He knew that once the news went beyond gossip, the already steadily mounting prices for his art would double and triple, a phenomenon he found ghoulish and disturbing. He was also sifting through choices for the right forum to make the private public.

Meanwhile, he kept abreast of all the goings-on at ACT UP, mostly through Swen Swenson, a Broadway song-and-dance man in his late fifties, once nominated for a Tony for his performance in Little Me. Keith had met Swen when he began looking for a new home. Haring wished to leave behind the Sixth Avenue flat he was sharing with Juan Rivera, and he entered a contract on Swen’s town house on nearby Minetta Lane. After he was diagnosed with AIDS, though, he did not feel up to the extensive renovations required. Withdrawing from the agreement, he confided his diagnosis to Swen, who told him that he, too, had AIDS. He became an important confidant for Keith and a source of information about experimental medicines and about ACT UP.

Haring and Sean Lennon, June 27, 1988Courtesy of Keith Haring Foundation

Each Monday night, Swen would take literature distributed at the group’s meetings to Keith’s studio, where he often stayed late into the night while the two talked and Keith painted. “He was weaned into ACT UP by a friend,” said fund-raising committee chair Peter Staley. He was finally drawn decidedly to the group by a poster designed for a proposed action at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, featuring two black-and-white photographic images—on the left, Cardinal O’Connor, wearing his stately miter; and on the right, a used condom the same size and shape as O’Connor, with a big, red headline: “KNOW YOUR SCUMBAGS.”

“Okay, that’s it. I have to check out a meeting!” Keith told Swen. “Do you think I can get some extra copies?”

ACT UP had its share of celebrities turning up. Susan Sarandon and Martin Sheen were at recent meetings, and both wore “Silence = Death” pins on late-night TV talk shows and at awards ceremonies. Yet when Keith Haring showed up at his first Monday night meeting, there was an audible buzz. “He would walk in and stand in the back, definitely trying to blend in,” says George Wittman, who had assisted Haring in painting the mural at the Gay and Lesbian Community Center. “I saw him dozens of times at the Monday meetings and at the actions.” The crowded meetings made Keith feel more comfortable for the first time with his sickness, as he experienced strength in numbers.

Anytime I approached Keith to do something for the epidemic, the answer was always yes.

–Sean Strub

He eventually agreed to become a “public person with AIDS,” coming out as HIV-positive in a fund-raising letter for a large mailing of about two hundred thousand, while also committing to an interview with Rolling Stone magazine, where he would be honest about his status.

“I don’t want to be pitied,” Keith first said when approached by ACT UP. “It’s not because I am sick that I think people should feel terrible about AIDS.” Yet he eventually came around, convinced from a decade of activism that “the only way to deal with something negative is to change it, turn it into positive action.”

Scheduling was difficult, and [POZ founding editor] Sean Strub, active with Staley on ACT UP’s fund-raising committee, finally arranged to meet with Haring in his white-and-gold Louis XV–style suite in Paris, where he was staying with Gil, to talk through the letter.

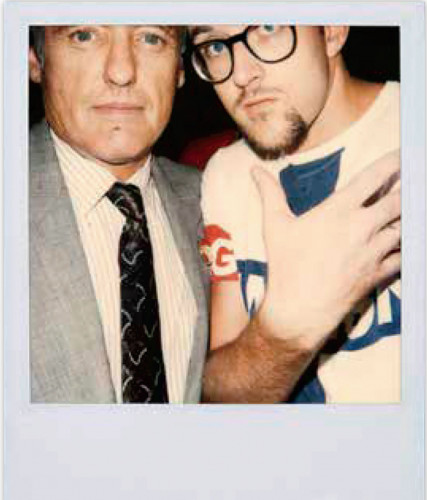

Haring and Dennis Hopper in Düsseldorf, Germany, August 1988Courtesy of Keith Haring Foundation

“It was late morning,” Strub says. “He was still in his pajamas. Gil came out of the bedroom once for a glass of orange juice and then went back in.” Keith showed a surprising interest in discussing the economics of direct mail fund-raising and asked after a mutual friend he had heard was battling KS. “I started explaining KS to him,” Strub says. “He said, ‘I know.’ He leaned over and pulled up his pajama leg, and he had massive necrotic plaques of KS the size of one’s hand on his shins on both legs. I found that moment sobering. I knew he was positive, but seeing that was so intense.”

Haring’s letter, which he opened by describing seeing his first KS spot in Tokyo, was written in laser font in his own handwriting—new technology at the time. It was soon completed, yet ACT UP was short the money needed for the bulk nonprofit postage rate. In such tight spots, Keith often made cash donations. Once, after he told Peter Staley, “I kind of have a cash business these days,” Staley stopped by his New York studio: “He’d grab his knapsack and pull out a wad of hundred-dollar bills, the first time, ten thousand dollars, and I’d carefully walk to the bank and deposit it in the ACT UP account.”

Haring’s direct-mail letter netted the group seventy thousand dollars. He also designed a see no evil/hear no evil/speak no evil–style “Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death” poster and paid for twenty thousand copies of it to be printed in Queens; gave money for buses to take demonstrators to the Montreal AIDS Conference; sponsored a benefit dance at the Sound Factory; and donated artworks for auction. “Over one third of ACT UP’s ’89 receipts,” Staley said, “can be attributed to Keith Haring.” “Anytime I or anyone I knew approached Keith to do something for the epidemic,” Strub says, “the answer was always yes.”

Excerpt from Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring by Brad Gooch. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2024 HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

Comments

Comments