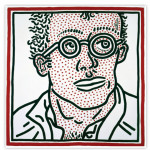

Roger Montoya’s life has everything to do with passion. Currently an artist and an active member of Española Helps, an AIDS task force in northern New Mexico, Montoya has taken an unusual route to his destination.

A childhood devoted to competitive gymnastics landed him a scholarship to California State University at Long Beach. When an injury there ended his competitive career, Montoya quickly channeled his love of movement into dance.

In the 80s Montoya would become a member of several prestigious modern dance companies, including those of Paul Taylor, David Parson and Mary Jane Eisenberg. But as Montoya’s dance career was developing, so was the AIDS pandemic. In 1984 after two years of nursing his first lover through the disease, the two of them left Los Angeles to build a house near Montoya’s family home in New Mexico. After his lover’s death later that year, Montoya moved to New York City. He tested positive for HIV antibodies but continued to dance; as the disease’s toll mounted all around him -- with friends, fellow dancers and new lovers all lost -- Montoya felt as if he were just waiting for the virus to catch up with him. His life was busy, but he made no plans.

Then, in 1990, Montoya got tired of waiting. He made a decision to make a difference and began living what he has since boldy called an “HIV-enhanced life.” Montoya moved back to New Mexico, resumed building his house and returned with new vigor to a passion of his that pre-dated even gymnastics -- painting. Building on skills he had developed as a child and then neglected, Montoya slowly began to relearn painting by focusing on the New Mexico landscape -- a resonant subject for him. Montoya describes himself as being of the earth and devotes a huge amount of time to his garden. He notes that, even under adverse conditions, he has always maintained a connection with nature. “In New York [City], my fire escape was gorgeous. I rigged mirrors above it to bring in more light.”

His painting career was jump-started a couple of years ago when a local author saw his landscapes at a crafts festival and asked him to submit some figurative paintings to illustrate a children’s book she had written about an Indian girl. Given a short deadline, Montoya worked around the clock to complete 11 paintings in 16 days, an experience he compares to completing art school in two weeks.

Despite his commitment to art and his garden, Montoya has never forsaken his love of movement. In 1990, Montoya got a grant from the University of New Mexico to teach gymnastics to local children. Montoya has already taught gymnastics to more than 1,000 children ages 4 to 14 in northern New Mexico. But, while living an HIV-enhanced life in New Mexico, Montoya had not yet fulfilled his promise to make a difference. It was with his students that he felt this need most clearly. The vast majority of his students are Latino or Native American. Montoya believes neither culture deals with disease particularly well. “It’s a gigantic problem. There’s just silence and, underneath, it’s festering. Indians hide disease, period.”

Early this year he began to come out as a gay man and as HIV positive in order to raise the topic with his neighbors. The difficult part would be telling his students. “I’ve always worked with children,” he says. “They keep me alive. For the last four years, in the back of mind has been: What do I tell the children?”

This past spring Montoya sent out a flyer inviting students and their parents to a special meeting. At first he couldn’t speak, but after tears and struggle he was finally able to tell his story. He spoke candidly about his condition and about how difficult it is to transmit HIV and assured his audience that he wouldn’t be teaching if he had any fear at all that he might be endangering his students. Montoya spoke for about 25 minutes. To absolute silence.

When Montoya was finished, the father of one student accused Montoya of infecting his family and took his child and stormed out. Several other students have dropped out of Montoya’s class since then, but most have stayed and Montoya says the classes remain energetic and focused. And the kids have been clamoring for AIDS education.

In response, this pas Memorial Day, Española Helps organized a weekend full of activities to increase AIDS awareness, featuring an exhibition of Montoya’s art, AIDS awareness messages delivered in churches throughout the Espanola Valley, and performances by local singers, dancers and Montoya’s gymnastics students. Montoya was the driving force behind the celebration which devoted the whole day to youth. “We have to start as early as possible,” he says. “By being so honest, the kids really get it. You can see it in their faces.”

Montoya strongly believes in the honesty of the body. He remembers how AZT made him feel. “If you don’t want to eat, that can’t be healthy.” His treatment for HIV since discontinuing AZT has included his own organically-grown produce, vitamins, massage, Chinese herbs, colonic therapy and acupuncture. It bothers him that although considerable money is available to help people purchase AZT and other conventional treatments, “none is available for those who choose natural alternatives.” In response, Montoya has officially proposed that New Mexico AIDS Services set up a voucher system for client access to alternative treatments. Through generous donations of his art, he has personally begun raising money to set up the funds behind the voucher system. “I’m dedicating the rest of my life to alternative therapies,” says Montoya. Familiar now with this tireless gymnast/dancer/painter/teacher, we are left with only one question: The rest of which life, exactly?

Tumbling Run

Artist Roger Montoya takes the long road home

Comments

Comments