It is an appropriate show for an unseasonably warm fall day in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. A wall-sized grid of 155 black wire leaves absorbs the brilliant sunlight in the gallery, each work a tender tour de force, a portrait-tribute to a friend of artist Eric Rhein who has died of AIDS. Every slight steel leaf is encased in a shadow box, making it a mini-shrine. The effect is oddly comforting: There’s “Terry With the Healing Hands” and “Orsini the Sky Painter,” playfully titled works that must conjure up a flood of recollections for Rhein, and likely for other viewers as well. Leaf Portraits is his memory bank, an elegy that—until recently—we might have considered an old man’s art form.

Rhein, though, isn’t old: He is 37. The elegiac quality of his work is instead a sign that the Lazarus effect—the return to health so many people with AIDS have experienced in recent years—is now being felt in the art world. Rhein conceived the show in 1996 after starting a successful course of treatment with protease inhibitors. “I was at an artists’ colony in New England, which I wouldn’t have been healthy enough to attend even a year earlier,” he recalls. “And I had what I can only call a mystical experience. I was walking on the grounds in autumn leaves, and I felt like the spirits of those who’d died were supporting me, teaching me to walk again.” As Rhein picked up leaves that reminded him of the appearance or personality of particular friends, the project was born. It continues to grow, with Rhein adding new works. Still, he reserves the right to remake any piece that is sold so that this personal archive will remain intact.

Leaf Portraits is a perfect emblem of the new ways AIDS is affecting the art world today. Bearing little resemblance to the challenging and outward-looking works that characterized the activist heyday of AIDS art, works by artists with HIV now often reflect on the body or, like Rhein’s, the memory—if they are about AIDS at all. Few works about the epidemic appear in galleries today. Many collectives have dispersed, and many artists have moved on to create different, unrelated work. And, of course, too many artists with AIDS have died.

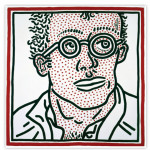

Only a handful of years ago, you didn’t have to travel to galleries in SoHo or Los Angeles to know about AIDS art. It found you. For several years beginning in the mid-1980s, it regularly appeared on front pages and TV screens. While some artists, such as Ross Bleckner, Keith Haring and Nan Goldin, were embraced by the museum world, the most remarkable artistic innovations of those years were public projects and actions, including the Names Project Quilt, “Silence = Death” and the Red Ribbon Project. No schmaltzy Elton John song or sappy Jonathan Demme film ever gave the syndrome a human face or inspired activism. Instead, it was visual artists who took up the task of creating the emblems and community artworks that would not only crack open the art-world closet, but redefine AIDS.

“Silence = Death” and the Names Project Quilt burst onto the scene in 1986—a time when Ronald Reagan had yet to utter the word AIDS in public, and the biggest AIDS news stories to date were unsavory accounts of Rock Hudson’s death. In 1989, Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, a show of funky AIDS-themed art, nearly brought down the National Endowment for the Arts when it opened at Artists Space in New York City. Too AIDS- and sex-positive for the Beltway crowd, it came just six months after the right-wing assault on “Piss Christ”–maker Andres Serrano (too sacrilegious), five months after the cancellation of Robert Mapplethorpe’s exhibit at the Corcoran in Washington, DC (too queer), and one month before the first Day Without Art.

Gran Fury, the hell-raising collective that arose from an ACT UP project at New York City’s New Museum, also emerged at this time. Not only did the collective nearly get itself indicted for obscenity for exhibiting its stunning “Pope Piece,” which skewered the Pope for his lethal anti-safe-sex beliefs at the 1990 Venice Biennale, but it raised hackles in this country in 1989 and 1990 for its street-spanning banner for a New York City Day Without Art exhibition at the Henry Street Settlement that read “All People With AIDS Are Innocent” and for its famous Benetton ad–inspired image of three interracial homo- and heterosexual couples kissing above the caption “Kissing doesn’t kill. Greed and indifference do.” When it appeared on the sides of buses as part of Art Against AIDS’ Art on the Road project, it prompted a Chicago alderman to call the work “an incitement to homosexuality.” Who knows? Without AIDS, the culture wars might still be a bush-league skirmish in the Bible Belt.

Activists were not only producing their own art, they were challenging the art world as well. The 1988 exhibition of Nicholas Nixon’s unsentimentalized photos of people ill with AIDS catalyzed an ACT UP demonstration at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art demanding images of PWAs “who are vibrant, angry, loving, sexy, acting up and fighting back.” (Today, in an ironic reversal, many of us are appalled to see so many healthy-looking people with AIDS smiling at us from pharmaceutical ads, as if they weren’t ill at all.) The same year, gay opponents torpedoed San Francisco artist Rudy Lemcke’s Zen-inspired AIDS memorial garden because they objected to $250,000 being raised privately for art, rather than for research or treatment. Most broad-based was Day Without Art, an annual “international day of mourning and action in response to the AIDS crisis” that I helped launch in 1989, which forced the art world to confront the effects of the epidemic within its own institutions.

That fewer emerging artists are creating works about AIDS today—or trying to politicize the art world around AIDS—isn’t surprising. The symbiotic relationship among art, activism and the media no longer holds, now that an increasingly conservative media has stopped regarding AIDS in the United States—not to mention art censorship—as news. Perhaps more important, AIDS is no longer generally experienced as a crisis. As prevention theorist Michael Wright pointed out at the National Lesbian and Gay Health Conference in Atlanta in 1997, the issue is psychological as well as statistical: “I still see campaigns for ASOs [AIDS service organizations] that characterize AIDS as an emergency situation. In the beginning AIDS was an emergency, but no emergency lasts 17 years.” He and many others believe it’s time to jettison the military metaphors of a national security–style emergency and adhere to the more sober view that, while daunting public health, education and civil rights dilemmas remain, for some Americans, at least, there has been progress.

Just as the character of AIDS art has changed, so, too, has the nature of art-world initiatives to support artists with HIV. Last December marked the 10th anniversary of Day Without Art. Is it a sign of the times that in 1998, a decade after this event debuted in a moment of dire urgency, the day showcased the premiere of an art archive? A project of the Estate Project for Artists With AIDS, the Virtual Collection is an expanding database of 3,000 digitized images of artworks created by 150 artists either lost to AIDS or living with HIV. To compile the data, the Estate Project’s director Patrick Moore worked with archives across the country, from Visual AIDS in New York City to the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center.

Now this material has been shaped into a scholarly and curatorial resource to be housed in museums and universities. It is also available online, for anyone with Internet Explorer 4.0+, at www.artistswithaids.org, although at lower resolution and without some of the innovative software developed for museums. The website offers images by artists from around the country fleshed out with biographical information; the museum version includes a variety of bells and whistles, such as searches by medium or geography and the ability to collate images for virtual exhibitions onscreen.

The Estate Project’s venture seems to indicate that AIDS-art activists, who at one time put pressure on the institutionalized art world, are now collaborating with the cultural institutions they once critiqued. Moore himself is quick to point out that the Virtual Collection is not an activist project. But his characterization may be off the mark. He is busily ensuring the preservation of activist videotapes by the likes of James Wentzy, Catherine Gund Saalfield and Gregg Bordowitz. Their documentary tapes are being remastered and will be available at the New York Public Library, and eventually online. The tapes will offer an intimate look at activist history to a generation that was still in high school when ACT UP stormed the stock exchange.

The Virtual Collection, meanwhile, is conducting its own battle on behalf of PWAs—a battle against historical erasure. At the Museum of Modern Art event inaugurating the Collection on December 1, Kinshasha Holman Conwill, director of the Studio Museum of Harlem, noted that “for artists, invisibility is a kind of death.” The corollary is that for most artists, making art is synonymous with being alive. Matisse famously crafted his gorgeous cut-paper works of the ’50s from his bed, even when he was no longer able to paint. In the era of AIDS, many stories resemble that of Tony Greene—a talented young Los Angeles painter who refused to die until his last show was safely hanging on gallery walls. Just before that show opened at New York City’s Feature gallery in late 1990, he told me that completing it had added meaning to what he knew would be his final days. “I’m thrilled knowing it’s done,” he said. “I feel much more resolved.” Serving artists means serving their work—whether they are living or dead.

The art world of the past 25 years has tended to mirror—and often predict—issues bedeviling society at large. It is no less conflicted now about where we are vis-à-vis AIDS than the American public. Consider Visual AIDS’ Day Without Art poster this past December. It features an image of an apple pie and a text that begins: “AIDS. It’s not a problem anymore—right, Mom?” It goes on to enumerate a depressing litany of facts: 25 percent of those who become infected with HIV are under age 20; in 1997, 55 percent of Americans believed they could become infected by sharing a glass of water. (This is 7 percent more, by the way, than subscribed to this idiocy in 1991.) As the poster proclaims, the epidemic and AIDSphobia continue to rage—yet we all know people whose health has improved dramatically.

Can such seemingly contradictory views of the current status of the epidemic be reconciled? Perhaps the challenge is asserting that AIDS is both past and present by advocating a far more nuanced view than is generally held now. And coping with our accumulated mourning even as we celebrate declining death rates. As visual artists helped stoke the rage of early AIDS activism, so too is there a vital place for artists at this moment of reckoning. Art has always played a role in coming to terms with collective tragedy, and the role of the artist has frequently been to bear witness. Surely an art of memory like Eric Rhein’s can help harmonize our views by suggesting that honoring the past is one way to live more fully in the present.

Does the archival impulse behind Rhein’s work and the Virtual Collection signify the belief that the epidemic is past? It is at least a reminder that some AIDS art has already entered history. Many brilliant artists showcased in the Collection’s initial online presentation—photographers Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar and collagist David Wojnarowicz among them—are long dead. Their challenging work now hangs in museums and private collections, and its fate has been entrusted to galleries handling those artists’ estates. In the case of artists who never had careers that ensure the preservation of their work, the Virtual Collection offers a record that, in some instances, may also lead to the work’s physical survival. All of this artwork—known and unknown—is the stuff of history. Happily it is now more available to scholars and curators, who can interpret it and make it accessible. Future art historians will debate its value, but art history is only a record of what survives.

When Patrick Moore concluded his demonstration of the Virtual Collection December 1 with an image of “Silence = Death,” the collective pulse quickened in the Museum of Modern Art’s dimly lit auditorium. The brilliant emblem-cum-artwork has come to symbolize the courageous contributions of AIDS activists who have revolutionized everything from the way people suffering from illness see themselves to the delivery of drugs and health care. There are only a few 20th-century artworks—such as Picasso’s “Guernica”—for which such political claims can be made.

I was struck by this when I received an anonymous AIDS artwork in the mail recently. Attributed only to “Policewoman,” it included a crack-and-peel sticker modeled on the Visa logo and emblazoned only with the acronym AIDS. The accompanying press release, imitating a credit-card offer, announces, “You have been pre-approved to received the enclosed tri-color AIDS banner…. It will cost you nothing to accept and in so doing you will gain the satisfaction of knowing that your display of it will put AIDS back into the public eye.” As public art goes, it’s pretty thin, not more than a one-liner. But whatever one thinks of it, I am certain that a public media artwork cannot be effective without widespread distribution and media involvement. Ironically, the only other person I know who saw the AIDS logo—in or out of the media—was my editor at POZ. Talk about preaching to the converted.

Eric Rhein (B. 1961), “Leaf Portraits,” Wire on Paper (1996) Courtesy of the Estate Project’s Virtual Collection

How to Make Art in an Epidemic

Visual artists turn from street posters to quiet elegies

Comments

Comments