Growth is directional—upward, outward, inward. In plants, growth can be as visible as a fuchsia necklace of Dicentra bleeding-heart flowers, or the humbling altitude of Sequoia sempervirens redwood trees. Plant growth can also be imperceptible to us people, like the hidden deep peg roots that combine with a filigree of fine roots to anchor the kauri tree, or the life span of water lotus seeds that can germinate after hundreds of years.

In July 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic continues, but in New York City (where Visual AIDS is based), in-person connectivity is flowering, nourished by warm weather, vaccination access, and continued precautions at gatherings and among friends amidst reopening. Across the nation and the globe, however, nations and communities are facing resurgences and continuations of the necessary physical safety regulations, and the unnecessary and imbalanced loss of life precipitated by hypercapitalism, racism, and vaccine apartheid.

This Florece / Flourish web gallery takes a cue from the phenomenal movements of plants, to create a metaphor for a moment where in-person communal life is unfolding in some places, and adjusting inward in others. And no matter the conditions that surround us, it is important to acknowledge that expansion is one way to grow, but shrinking, stopping, turning inward or turning away are also growth, and life-giving. In plants, tropic movements—coming from the Greek “a turning”—are outward movement in response to stimuli, such as turning towards the sun or oxygen. Nastic movements-- coming from the Greek “pressed” or “the condition of being pressed upon”— include shrinkage or swelling, or the closing or opening brought on by night.

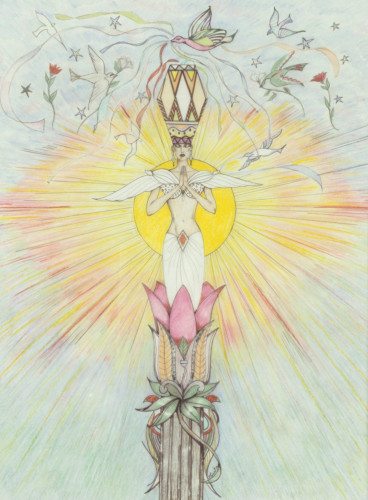

Lucretia Crichlow, Title unknown , c. 1990-94 work on paperCourtesy of Visual AIDS

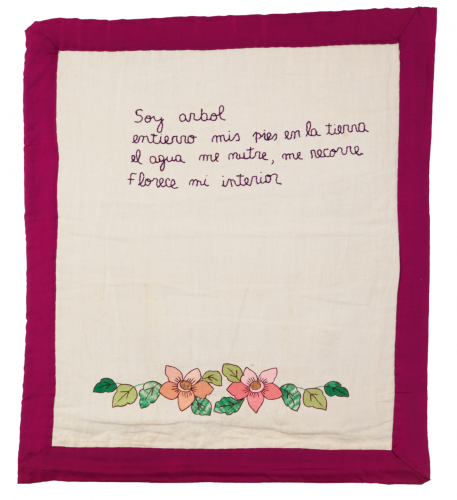

Exploring the accessible, online Artist+ Registry—which has provided a virtual platform for visibility for artists with HIV and AIDS since 2000— through the lens of this theme was a joy. A radiant work on paper by Lucretia Crichlow shows a femme emerging from parted petals, bedecked with ribbons and roses by swirling birds, setting a tone of emergence and warmth. In three works by Feliciano Centurion, germination, watering, and flowers are embroidered evocations of internal flourishing (“florece mi interior”) and survival as affirmation (“estoy vivo!”). Flourishing is also invoked in the performance Mi Florecimiento by Juan de la Mar, combining flowers-as-adornment with a sense of militancy, and a sweet kiss, as well as in a large-scale collaged and embroidered textile by South African artist Pippa Hetherington in collaboration with the Keiskamma Art Project, where a portrait of a Black Eastern Cape Xhosa woman elder is ensconced amidst plant life, dyed with the same clay that nourishes growth.

In works by Leomar and Tony Feher, floral growth is made sculptural, both mournful and celebratory. Remembering Ms. Colombia’s floral style, a joyful image of her taking center stage at the 2013 Coney Island Mermaid Parade includes stylized daisy details of the amusement park architecture. Several artists offer flowers in gestures of care and acknowledgement—Shirlene Cooper’s LOVE YOU Valentine, IMH’s “symbolic gesture” of A rose for them and the fruits of her garden care, Orlando Ferrand’s tantalizing Honey for the Boy, and Dee Stoicescu’s pressed flowers adorning microscopic virus images. Finally, Veritee Red Hall and Kissa Millar give an expanded sense of how sun, seasons, and environment nourish all this growth.

Feliciano Centurión, Florece (Flourishes) , 1995 Embroidery with inclusion on blanketCourtesy of Visual AIDS

Interspersed with all of the flowers is the reality of the challenges in this moment of flowering for some, and the “condition of being pressed upon” that can close up petals but keep growth flowing within. Liliana Maresca’s ETA represents a transition piece, an alchemical sculpture that solidifies the reaching roots of a branch into bronze hold, fixed. In works by Michael Colgan, Shan Kelley, and Eric Tenorio, windows act as portals, connecting interior and outside spaces—and isolation and physical connection— with feelings of trepidation, love, and self-reflection, respectively. Chloe Dzubilo’s Untitled (I Ask Myself) shows the artist’s body wrapped in hearts, and the caption reveals the incredible struggle to move, to even get out of bed, through daily pain. In Sunil Gupta’s Shroud/Pleasuredrome, the artist lays in bed, shrouded, juxtaposed with the memory or the motivation of the sauna space. Out in the world, the subjects of Carlos Sanchez’s work—the everyday people of Venezuela in 2017—are denied medicines due to scarcity, reminding us of the treatment imbalances of an inequitable world.

Out in that world, in Garland Eliason-French’s Graduation Day, a doubled figure seems to emerge amidst shells and nature—but is surrounded by a menacing crowd of grimacing faces. Jessica Whitbread’s humorous yet on-point collaboration with Morgan M Page/Odofemi, Space Date, shows outerworldly protection as a reference to HIV criminalization, but takes on a new resonance in regards to reopening and safety procedures. Finally, in Nicolas Moufarrege’s historic work First Steps into the Pyramid, a figure leaves a sepia-toned plane, taking a firm step forward into a shimmering pyramid of color and light, as resplendent as the flowers offered by this web gallery.

Click here to view the entire gallery on the Visual AIDS website.

Carmen Hermo is the Associate Curator for the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. She curated “Roots of The Dinner Party: History in the Making (2017),” “Kameelah Janan Rasheed: Are We Reading Closely? (2020),” “Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive” (2021, forthcoming)," formed part of the “Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall (2019)” curatorial collective, and co-organized “Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection” (2018) and the Brooklyn presentation of “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” (2018) among other exhibitions. Previously, Carmen was Assistant Curator for Collections at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and worked with the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art. Carmen received her B.A. in Art History and English from the University of Richmond and her M.A. in Art History from Hunter College.

Comments

Comments