By Reed Vreeland (Intern, POZ)

I’ve always systematically avoided the AIDS Walk. I avoided it growing up because in school it’s the one occasion when HIV/AIDS comes up in conversation, and that made me uncomfortable. I didn’t want to be associated with HIV. I didn’t want people asking me about it. And I absolutely didn’t want to be defined as the “kid with HIV” in hushed conversation, even though all of my classmates were aware of my diagnosis. Plus, for me wouldn’t walking be the equivalent of asking for money for myself?

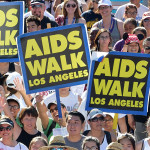

On May 15th I finally participated in my first AIDS Walk, New York’s 26th annual. It’s been a long time coming--I’m 25 and have lived with HIV for 25 years--but going into the walk I was most curious about what was motivating 45,000 other people to walk. How many of my fellow walkers’ lives have been directly touched by AIDS?

Watch video from AIDS Walk:

The Inception moment that inspired my decision to walk happened several years ago, when I was on the subway and overheard two sporty high school girls chatting about the AIDS Walk. They absolutely dreaded going again. They made it clear that they were grudgingly walking, purely out of obligation--HIV/AIDS didn’t seem to be a reality for them. As I left the subway I realized that for these two girls the AIDS Walk could be substituted for any “good cause.” Yet there I stood: these two girls were walking and I wasn’t. How could I be critical of what they said if I wasn’t walking myself?

This year I finally put my thoughts into action and my fiancée, Anna, was walking by my side and helped spur me out the door on time. When we emerged from the Q train onto the southeast corner of Central Park, there was an antic flutter of energy in the air and the sidewalks were brimming over: people were standing inertly, clothed in ready-to-walk outfits, holding hand-made signs, walkers were weaving through bodies, some shouted out to friends and engaged in the kind of pre-game banter you hear before sports games.

For an individual the AIDS Walk can have deep symbolic resonance: some people walk in memory of someone taken by AIDS; some walk because of a positive diagnosis. Walking can mean remembering. Walking can represent coming out about being HIV positive. Walking can be a step toward self-empowerment and confronting the virus. Or walking can be for school credit, for frat or sorority community service, or the call to walk can come from some greater sense of obligation, because it’s the “right thing to do.”

When I looked at the many individuals that surrounded me (all merging into cells that together formed one great, moving mass) I was trying to imagine what the resonance the walk held for the people around me. I found myself unable to even guess.

The remainder of the POZ group was made up of two of my new, intrepid coworkers from POZ, Jennifer and Giovanni. Anna and I finally spotted them after the opening ceremony--Jennifer was dynamic and full of documentarian zeal, hurrying to capture choice shots with her camera and flip phone. Giovanni was prepared for the rain and set a steady pace as an AIDS Walk veteran, having soldiered through eleven consecutive AIDS Walks, not counting two in Los Angeles. Giovanni was also the man behind POZ’s AIDS Walk fund-raiser, Love Out Loud. My coworkers have been at POZ for a collective 13 years, and I just started as an intern in April.

Our newly minted group followed the pull of the crowd and set off on the 6.2-mile route around the park. As we walked, Jennifer told us about the celebrities she’d interviewed for the magazine. At one point we passed a group of rowdy high school kids--my rough estimate puts a safe majority of walkers under 30. “These little ones have never known a world without AIDS,” Giovanni said. I reminded him that I, being 25, haven’t either. He told us about when he first heard about AIDS. “I remember when there was no AIDS,” he said. The jolt of his statement, the fact that he needed to say it, spoke to how much it had shaken his life.

Giovanni also explained how the walk has changed over the years. “You don’t see much of the Old Guard anymore,” he said almost wistfully at one point. He gestured toward a man ahead of us who wore a cardboard Star Walker crown over graying hair. When we were crossing a major avenue he singled out two tan, chiseled men in twin sleeveless red t-shirts, one with a well-groomed mohawk. "It used to be like that,“ he said. Looking at them I could summon an image of the legions of gay men who championed the AIDS Walk in its formative years. The ”Old Guard" had a mystical ring to it coming from Gio.

Later Giovanni described what it was like to participate in the candlelight vigil during the AIDS Quilt Walk in Washington, DC. “That walk had more gravitas,” he said. “It was when people were still falling.” Giovanni saw too many friends die in those years. He remembers traveling to Philadelphia to view sections of the AIDS Memorial Quilt. "I saw a patch for Timothy Scott, from the original cast of the musical Cats,“ he told me. ”Until then I didn’t know that Tim was dead."

The loss that Giovanni felt was still raw as he talked. I could feel his pain in my chest along with my own. For me the pain was coming to the surface as we walked side by side, with Anna and Jennifer next to us. The route was long enough to give us plenty of time to think. But the more I walked, the more mental energy I dedicated to keeping up momentum. Eventually I got separated from the group and started walking alone.

It was when I was walking alone that I started to notice that there was almost no interaction between different groups. I felt completely anonymous. The barriers between cliques only ossified as the walk continued and people became more exhausted and single-mindedly set on finishing.

It was also plain that the Old Guard was now only a token force. People of color had become the AIDS Walk vanguard, African Americans and Latinos were dominant in numbers. Youngsters were ubiquitous, but a lot of the kids I saw lacked discipline. After we were handed granola bars at Riverside Drive’s Checkpoint 2, I could see wrappers littering the street for miles. If these kids weren’t able direct garbage into trashcans, would they have the discipline to practice safe sex? Being wedged between two high school groups felt like being part of a giant class field trip.

Eventually I sidled up to two young ladies handing out bright-blue American Eagle t-shirts, still wondering if the majority of young people walking were like the two girls on the subway. “Why are you guys walking?” I asked. "I’m walking for my grandfather--he died of AIDS two years ago. Why are you walking?" The American Eagle scout’s reply was a one-two punch that caught me off guard.

I didn’t expect the weight of her question or the pained quickness of it. I didn’t expect either of them to have a connection to walking--they seemed too young, too carefree.

"I’m here with POZ magazine,“ I said. ”Trying to ask why people are walking." My reply felt cold and unsatisfactory. I didn’t tell her that I have HIV or that my mother died of AIDS also, so I guess I’m walking for her. I didn’t say any of that. I just choked on my own words, eventually losing them in the crowd.

A mile later I was able to redeem myself when speaking with a recent college grad walking with her friend. Her mother died of AIDS in 1999. “I’m walking for my Mom, too. She died in ’96.” These were the words that had been so hard to say before. I hadn’t been prepared to say them because I wasn’t prepared for the question or for shedding my anonymity.

By the end of the walk I understood how those two girls on the subway could go through an entire AIDS Walk without a greater understanding of the cause. If I were a young walker with only a schoolbook understanding of HIV/AIDS, would I feel comfortable approaching a person in a different group? Growing up, hadn’t I always snapped at the kids in my class who approached me about HIV? Or if I didn’t snap, hadn’t I made talking about HIV uncomfortable, maybe as a subconscious defense mechanism? In my experience it takes effort and hard work to openly talk about HIV, and based on my recent AIDS Walk experience, I think a lot of us have along way to go.

Let’s start with the questions:

Why did you walk?

Why did you not walk?

Will you talk to the people around you next time?

7 Comments

7 Comments