While HIV remains a contemporary scourge, the history of the disease has increasingly been the focus of journalists, scholars and curators, among others. Fusing text and images, HIV and AIDS posters have urged people for decades to protect themselves, protect others and to question—and even change—their own behaviors. Employing innovative graphic design, HIV and AIDS posters have also inspired protest and forged a sense of shared identity among activists. Three recent art exhibitions emphasize the pivotal role played by HIV and AIDS posters since the virus emerged in the early ’80s. Donald Albrecht drew from the poster collection of the University of Rochester’s River Campus Libraries’ Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation to curate Up Against the Wall: Art, Activism, and the AIDS Poster, which was presented at the University’s Memorial Art Gallery. Andy Campbell worked with the ONE Archives and ONE Archives Foundation to curate Days of Rage, a multimedia online exhibition featuring activists and designers discussing their work. Theodore (ted) Kerr organized the online exhibition AIDS, Posters & Stories of Public Health: A People’s History of a Pandemic for the National Library of Medicine (NLM). Below is an edited conversation between the three curators on the role of HIV and AIDS posters.

From left: Donald Albrecht, Andy Campbell and Theodore (ted) KerrAlbrecht (Courtesy of Donald Albrecht); Campbell (Courtesy of Paige Schilt); Kerr (Courtesy of Issue Project Room/Cameron Kelly)

Kerr: Let’s start with the elevator pitch for each of our exhibitions and go from there.

Albrecht: The first large-scale exhibition and book devoted to one of the world’s largest collections of HIV/AIDS posters.

Kerr: An online and physical touring exhibition that uses the National Library of Medicine’s digital collection to showcase people’s response to HIV.

Campbell: A digital-born exhibition about graphic design and activism that seeks to bring design back to the body—it includes things like memory, touch and historical reflection—all that good stuff.

Kerr: Andy, it sounds like you were influenced by an exhibition you told me about a few years ago.

Campbell: Yes! There was a show called Protest in Place at SoLA Contemporary, a community-run gallery in View Park–Windsor Hills in Los Angeles. It was a show of posters made during the recent Black Lives Matter uprisings. It was still relatively early in the COVID pandemic, and the gallery was not open. You could only see the exhibition from the window. The curator, Peggy Sivert, hung the posters from the ceiling in a layered way, with an audio component from the protests. It provided a sense of what it was like to be in a protest action, to be in the middle of a crowd, but it also relied upon a sense of physical space beyond the usual modernist hang of a graphic design exhibition. This idea was important to me, although I don’t quote it directly in the show. Part of my exhibition focuses on a top-down camera view of people accessing the posters. This was related to something I started doing during COVID for lectures and presentations. I was using an overhead projector to physically manipulate images. I was feeling very disconnected from the physical space because everything was on Zoom. So the exhibition combines that seed planted by the SoLA exhibition and my own digital teaching strategies.

Kerr: My starting point was an invitation from the NLM to curate an exhibition as a follow-up to their earlier exhibition Surviving and Thriving: AIDS, Politics, and Culture. Within this scaffolding, I looked for posters that remind us that at the foundation of our work are communities making sense of bodies, desire, illness and care.

Albrecht: My experience also began with an invitation. The University of Rochester had come up with the idea of a collaboration between the library and the museum. I was hired to shape an exhibition. This was a large task. The poster collection was created by Dr. Edward Atwater and is among the largest in the world. With this in mind, I chose to make the exhibition as broad-based as possible. There have been exhibitions of Dr. Atwater’s collection before, but none at this scale and none at such a prestigious site in Rochester. I thought it would be wise to reflect the collection first, and then in the future people can pull out specific themes.

Campbell: Donald, what kinds of decisions did you have to make to give an accurate representation of that collection?

Albrecht: I took notes and noticed aesthetically that you have some very slick Madison Avenue advertising type posters and you’ve got simple line drawings; you’ve got posters for purely sharing information, and you’ve got posters that are providing information and correcting myths; and you’ve got posters that are urging action. I’d done enough research into AIDS and other poster shows to see what had been done before. For instance, there’s one exhibition that was organized by country, so I didn’t see a point to doing that. I decided to organize my show by message because that’s what the posters are ultimately about. I mean, while the aesthetics are important, it’s the messaging that’s significant. We were tied to a particular size of space of 5,000 square feet. There’s only so many posters you can put in there without getting museum fatigue. I think we ended up with about 165.

Campbell: I went through a similar process while looking at the more than 4,600 posters that have been digitized by ONE Archives. I found the experience deeply pleasurable because I found things I had never seen before and got new information to integrate and to build on what I already knew. Ted, had you ever seen the posters at the medical library?

Kerr: Not in person, but seeing them online produced a visceral response. I have a long dormant frustration regarding mainstream HIV prevention posters that dominated the gay bars and STD [sexually transmitted disease] clinics of my youth. They seemed like grant deliverables charged with warning me about HIV that failed to even hint at any of the other complex elements of the epidemic. Those kinds of posters upset me back in the day, and that resurfaced upon seeing them as a curator. But I pushed through and sought out proof of the individual hand or grassroots ethos of poster-making that I knew had to exist within the NLM collection. I became focused on the idea that people who cared about similar things to me had made something I could help share and contextualize years later.

Albrecht: I had a focus as well. For my exhibition, the visual quotient had to be high because I was curating for the Memorial Art Gallery. I had a predilection to like the things that were graphically very dramatic. I was also interested in how the AIDS poster builds on the traditional health poster and how it differs.

Kerr: Which you write about in the catalog.

Albrecht: Yes. We also included essays from the scholar Jennifer Brier and graphic designer Matthew Wizinsky, who wrote the cultural and social story; Dr. William Valenti provided a medical and historical perspective of what it was like in the trenches in Rochester in the ’80s; and the curator of the collection Jessica Lacher-Feldman, also contributed an essay. In addition, the catalog has about 25 to 30 deep captions that come from scholars, doctors, activists and others, who selected a poster and wrote about it, including Avram Finkelstein, who also wrote the preface—and you, Ted! It was a way to get lots of other people involved. And interestingly, the structure I set up for the show worked. Everything fit in the buckets, I made sure of it.

Kerr: I also had to consider gallery fatigue. I was lucky that the NLM has a strong team of experts who have a robust history of producing traveling offline and online exhibitions. The process begins with creating a set of six banners that institutions can order for display, so I thought of each banner as a room in a gallery. We used the content of these banners to produce an online experience. At first, I felt restrained, specifically as it applied to the online version. There was so much content I wanted to share, and it seemed online could be a place to really expand. But as I developed my checklist, I began to appreciate boundaries. While the internet might seem infinite, people’s attention is not.

Campbell: If it was just a matter of connecting people to the digital resource, we could have created an interface that displayed the 4,600-plus posters. But attention deficit is exactly the reason me and my cocurators, Tracy Fenix and Austen Villacis, didn’t do that. We created limits around the exhibition and initially invited five people to act as interpretive guides through whichever posters they selected from the collectiot. Each person would only pick five posters. So ideally, it would be a pretty limited and focused show consisting of five people, 25 posters. We wanted to do historical digging with rigor, but we didn’t have infinite time and unlimited capacity. So we created rules and then, of course, gave the participants the flexibility to break those rules. The first time that happened was when Judy Ornelas Sisneros, one of the people that we invited, said, “Oh, I want to do this with someone else who was in the trenches with me.” So Judy invited Jordan Peimer, and they did their segment of the exhibition together. And then another activist Alan Bell chose four poster series rather than five individual posters, so he ended up with 11 posters in total. His whole point in choosing multiples was that one poster could never bear the burden of representation by itself.

Judy Ornelas Sisneros, Jordan Peimer, and Andy Campbell looking at Jordan Peimer and Joshua Wells, AIDSPHOBIA: Protect Yourself from Hollywood, 1991Courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Kerr: I’m curious about what you think an AIDS poster exhibition can do.

Albrecht: Well, it can provide a general audience with a range of visual and textual expressions about AIDS across the globe. It can also tell the story of AIDS, reminding people of aspects of the disease’s history that may be forgotten. For example, there was a lot of misinformation in the early days around questions like, “How do you get HIV?” In terms of my exhibition, it’s a poster show at an art gallery, so we added a lot of information for context. To make the exhibit more specific to Rochester, the museum interviewed about a dozen local people about their experience of AIDS, which personalized it. What a poster exhibition can’t do is bring back the feeling and the experience of the time it was created. We tried to solve that throughout the show, with photo enlargements of some of the AIDS posters used in street protests, showing how they functioned in the wild.

Kerr: Andy, what do you think an AIDS poster or an AIDS poster exhibition can do?

Campbell: The show I curated was not specifically about AIDS. It’s an activist poster exhibition, but it’s fascinating that it almost functions as an AIDS poster exhibition, because for many of the people looking through these poster collections, AIDS was a primary touchstone. I don’t think we had a single person who didn’t choose something HIV- or AIDS-related. In terms of what an AIDS poster can do, I think I’d agree with Alan Bell, who said one poster by itself has a fairly limited scope. Most posters designed during the ’80s and ’90s were either targeted to specific communities or bound in some way to a message or way of thinking about where the crisis was at the moment. An AIDS poster exhibition can connect some of those points and identify holes in what we know about the entire body of graphic work that was and is still being created in response to the pandemic.

The interesting parts for me were when we would find a poster that had very little research behind it or that hadn’t really been written about in any way. We got the opportunity to do some of that research and present it. It was fun because we got to be a translator or interpreter for these historic documents. I think a poster exhibition can do connective and introductory work about the past and the present.

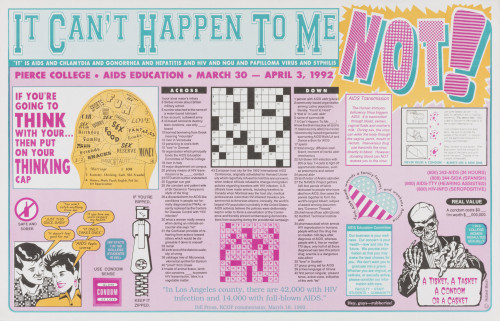

For example, through this exhibition I have come to better know the work of Robert Birch, who worked in Los Angeles under the pseudonym Cardiac Arrest. He made these funny and caustic posters about AIDS as well as for a variety of political causes and issues. What connects them all is a really strong graphic sensibility. He also had an awful and wonderful sense of humor. He was deeply involved in these causes, and he wrote letters to the editor all the time—there’s a paper trail. He was an activist and deeply disappointed by people who talked the talk but didn’t walk the walk. He feels like someone who I can learn a lot more from and who will hopefully make me a braver person in the world. In a way, the exhibition did for me what I hope it does for other people. It tells them about a past they may or may not be familiar with and then helps them imagine a future.

Robert Birch, It Can’t Happen to Me, Not!, 1992Courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Kerr: I used to discount AIDS poster exhibitions because so many of them were terrible. It was as if institutions felt they had to do something about AIDS, but instead of investing in the conversation, they just put up some posters. But two exhibitions changed my mind. The first was Safe Sex Bang: The Buzz Bense Collection of Safe Sex Posters, cocurated by Alex Fialho and Dorian Katz at the Center for Sex and Culture in San Francisco. It dove into the creative and lifesaving force of the posters and showed them as works of art and design and cultural touchstones. The second exhibition was AIDS: Based on a True Story, curated by Vladimir Čajkovac for the German Hygiene Museum. Using contemporary art and a bespoke inventory system, he cataloged the posters in terms of form and content. These exhibitions, like our chat today, helped me get over my cynicism and reminded me that AIDS posters can be many things, including artifacts of rich and complex conversations. They are proof that at some point someone was wrestling with an issue and worked to use text and images to share what was on their mind.

Campbell: There’s also this element for me of being around young designers—especially graphic designers—who are looking at a career trajectory that is often very much disconnected from their own communities. Their narrative is to start engaging in client-based work, maybe join an agency or a firm or to essentially put their skills to use in favor of industry. I think AIDS posters illustrate another way of being possible for formally trained graphic designers. You can see a light going on, and they think, Oh, I can turn what I’m most interested in doing creatively into something that actually matters to me.

Albrecht: Let’s talk about the posters and their designs. For me, I came into the exhibition thinking that most people, when they think of AIDS posters, think of the Silence = Death graphic or work by Gran Fury. But I found that the further we got away from those, the more interesting the posters became. For example, there’s a poster from China of a family with a smiling baby. It has to do with the theme of protecting the family, a common theme of health posters in general. This poster builds on that tradition. But it’s about the epidemic in a way that does not include any of the in-your-face graphics of the ACT UP work; it’s at the opposite end of the spectrum. In fact, unless you read the tagline, you wouldn’t know what the poster was about. It’s just a drawing of a cherubic child and his parents. The further the work took me, visually, away from what I expected, the more energy I got from it. And this became an important theme for the exhibition because one of the things I want people to walk away with is the global nature of the AIDS posters and Dr. Atwater’s vision.

“Silence = Death,” 1986, New York, New York; Creator: Silence = Death CollectiveCourtesy of the AIDS Education Collection, University of Rochester

Kerr: Fascinating. Growing up, images of ACT UP, Gran Fury, and Silence = Death were not easy for me to find. I primarily saw the type of posters I was complaining about earlier. There is something bittersweet about how once-elusive images of grassroots action are now the dominant images we consider as we curate.

Albrecht: A lot of the Gran Fury posters are very corporate-looking; by design, they are a riff on Madison Avenue advertising.

Kerr: Right. They used that strategy at the time to ape the dominant marketing style and capture the attention of the world. It worked in the era the posters were made and continues decades later. That’s incredible. It also means that part of our job as curators is to fill in the space between infamous activist images and images from the government and large nonprofits.

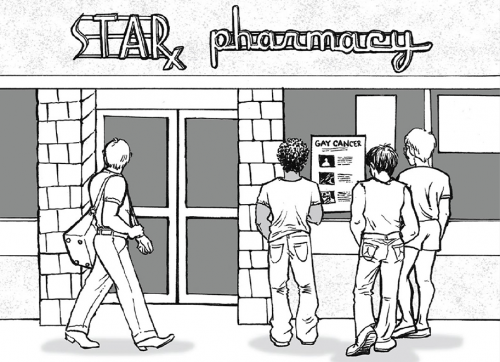

I wanted my exhibition to place the history of AIDS posters in time. The first image is a drawing of a historic photo of people gathered around a Castro pharmacy looking at a piece of paper in the window. That piece of paper is arguably one of the first AIDS posters. It was made by Bobbi Campbell. He was a nurse living in San Francisco, who dubbed himself “the AIDS poster boy.” He put pictures of lesions on his body on a piece of paper and wrote “GAY CANCER” in big letters. He instructed people to go to the doctor if they had similar marks. We were unable to get the rights to the photo for the exhibition, so we got creative.

Nurse Bobbi Campbell, producer HealyKohler Design, 2021Courtesy of National Library of Medicine

Campbell: You commissioned an illustrator to draw the scene! This was a really clever way, to my mind, of dealing with and of talking about lost historical items that we only know through other kinds of representation. I agree that this is where we have to be creative as curators and as people who are trying to tell historical narratives of various sorts.

Kerr: An irony I found doing this work was that it was often easier to find contextual information about a hand-drawn poster by an anonymous artist, for example, than a widely circulated image that came out of an advertising agency.

Campbell: There is an asymmetry in the research potential. The lack of information that you speak of around large organizations, like an ad agency, also extends to smaller ones that may have no archive per se. So it’s really hard to know how something came together. Whereas if one person is the creator, I could either find that person or find someone who knows that person to start figuring it out. It’s funny, because you would think the more atomized personal thing would be harder to locate, but certain kinds of small organizations or groups often don’t exist anymore. And I guess that’s another thing an AIDS poster exhibition can do: provide research and exploration into the work that has come before us and ask questions as a way to leave a trail for the work yet to do!

Comments

Comments