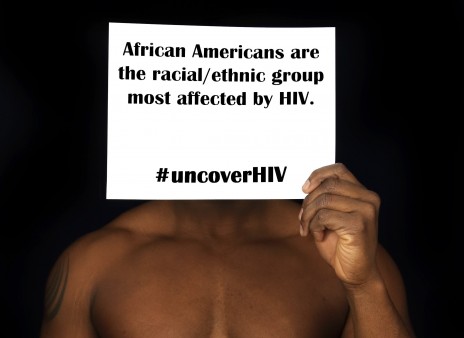

POZ readers likely know that “it can take years for HIV to develop symptoms,” but did you know that “8 of the 10 most vulnerable counties in the US for an HIV outbreak are in Kentucky” and that “African Americans are the racial/ethnic group most affected by HIV”? Residents of Lexington, Kentucky, are learning these and other HIV-related facts thanks to the testing and awareness campaign “#uncoverHIV.”

Central to the eye-catching campaign are photographs (collected in a gallery at the end of this article) of shirtless African Americans holding posters in front of their faces; on the posters are HIV facts like those mentioned above. The models are all locals—some living with HIV, others not—who reflect the target audience: people of color, notably heterosexual women, as well as men who have sex with men (MSM).

Images appear in online testing ads, on UncoverHIV.org, fliers and posters and, most prominent of all, on a billboard Lexington. They’ll also be displayed during the AIDS Walk in April and at local businesses such as salons for ethnic hair.

(continued below)

A billboard for the #uncoverHIV campaign in Lexington, KY. Courtesy of AVOL

The campaign has been received “extremely well” and is already getting results, says Pablo Archila, an HIV prevention specialist at AVOL (AIDS Volunteers Inc.), the local AIDS organization that launched the project with the help of nonprofit Bluegrass Black Pride and the HIV/AIDS branch of the Kentucky Department of Health.

“We’re sparking interest,” Archila tells POZ. “Since the campaign came out, we’ve been using those images and text in social media, and we’ve been getting so many more emails from people wanting information about testing and HIV—more than we got when we put out generic ads.”

It’s important work because many Kentuckians are at unusually high risk of HIV. Remember that HIV and hepatitis C outbreak two years ago in rural Indiana, the one linked to injection drug use? Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a list of 220 counties most vulnerable to a similar outbreak. It turns out that eight of the top 10 counties are in Kentucky, and Wolfe County, about an hour from Lexington, is in the No. 1 spot.

Kentuckians might not be aware of their HIV risks, Archila says, because many townspeople still think of the epidemic in terms of the 1980s and ’90s, when it was more common for gay men to leave the rural state for gay-affirming cities, only to return home to die of AIDS-related illness. “But that narrative is beginning to shift,” Archila explains, “as we see drugs like crystal meth and heroin in rural parts of the country, and we’re seeing more people infected with HIV.”

At the same time, he notes, HIV care has become more accessible, which makes outreach and testing more viable. “You can live in any part of Kentucky and get to a Ryan White clinic within an hour or two,” he says, referring to the government-funded AIDS program. “Before, that would have been impossible.”

In addition to raising awareness, the #uncoverHIV campaign has raised some eyebrows. While some folks deem the shirtless and bra-clad torsos too risqué for public display, Archila points out that the campaign is a play on words and that in real life, people will often undress and get in bed with someone without discussing sexual health and HIV risk.

“You can’t hide behind this campaign and these facts,” Archila says. “It’s staring you in the face.”

1 Comment

1 Comment