Since 2007, the Through Positive Eyes workshops have put cameras in the hands of people living with HIV and taught them to express their lives and fight stigma through photography. This World AIDS Day, December 1, sees the publication of images and paired stories by 130 workshop participants in a book by Aperture. A related exhibition, which includes live performances, is up through February 16 at the Fowler Museum at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Both of the projects are titled Through Positive Eyes, and both of them predominantly feature self-portraits, taken selfie-style or with a tripod and self-timer.

Launched by UCLA’s Art & Global Health Center and helmed by photographer Gideon Mendel and David Gere, PhD, professor of AIDS/arts activism and world arts and cultures, the project has included a total of 10 workshops in cities spanning the globe. You can view images and learn much more at ThroughPositiveEyes.org. POZ emailed Gere to discuss the project. His answers are below, followed by sample photos and stories from the project.

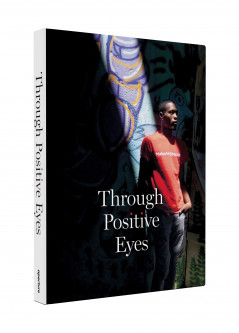

“Through Positive Eyes” is available World AIDS Day, December 1Courtesy of Apeture

How have the workshops and photography affected the participants?

So many of the participants—we call them “artivists,” part artist, part activist—report that photography has created a crucial outlet for their thoughts and emotions. Lynnea, from Los Angeles, wants to make a book of photographs about strong women living with HIV. She has the talent to do it.

What themes and narratives have surfaced through the project?

Stigma and its effects are everywhere in these images. Wilder, from Port-au-Prince [Haiti], made a photo of his hand encircled by razor wire and another with his head hidden behind a strip of paper that says, in Creole, “excommunicated.” Along the same lines, Gordon, from London, photographed his “bag of shame,” a clear plastic bag literally stuffed with all the nasty words he has been called. The heart of the project is a photo by Priya, in Mumbai. She is lying on a mat on the floor, snuggling her pet goat. She tells us that all her closest relatives have rejected her, but Julie, the goat, loves her unconditionally.

On the other side are delightful and humorous photos: Isaac in London with his underpants in his mouth—“I say pants-in-the-mouth to stigma”—and Maureen, originally from Zimbabwe, now British and living in London, posing regally beside a neighborhood sign that says “Nile.” There she is, Queen of the Nile.

We’ve noticed that stigma is particularly visible in communities where access to [antiretrovirals] is spotty or difficult. Humor, pleasure and joy come more easily to those in the [developed world], where, on account of better treatment, it’s possible to forget about HIV for long spans of time.

Workshops have taken place in Mexico City, Mexico; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Durban and Johannesburg, South Africa; Los Angeles (more than once); Washington, DC; Mumbai, India; Bangkok, Thailand; Port-au-Prince, Haiti; and London, United Kingdom. Are images in the exhibit taken from all the workshops, plus works by Gideon Mendel?

The images come from all 10 workshops, 2008 to the present. Present-day Los Angeles is represented by the members of the Los Angeles Through Positive Eyes Collective, who share their stories and photos live in the gallery.

The featured photos are all self-portraits, generally taken with tripod and self-timer, or sometimes selfie-style. At the beginning of the project, Gideon Mendel made a commitment to shoot his own portraits of each photo-storyteller. These images are beautiful and brightly colored, taken in people’s homes. Eventually, though, Gideon and I realized that the photos taken by people living with HIV were even more intimate and profound. Little by little, his portraits shrank down to become identifying thumbnails. They are now collected in a single composite quilt of images, depicting all 130 photo-storytellers. That’s how the exhibition begins, and it is also featured on the back cover of the book.

How have viewers and communities responded to the exhibitions?

I just received an email from a colleague in Los Angeles, who had brought along an “up-and-coming queer artist” friend to the opening at the Fowler Museum. [The colleague wrote that] “despite normally having an air of sangfroid he was moved to tears.” Emotions—not just tears, but relief and pleasure—run especially high in response to the live storytelling that is embedded in the exhibition. That’s where stigma and self-stigma start to fall away.

How does art like these photos tackle stigma?

The culmination of the exhibition is the Banishing Stigma room, where the artivists speak and share their photos. If stigma is what keeps so many of us from getting tested and treated, banishing stigma opens up the possibility of radical self-care. I see that happening in the exhibition.

Will the workshops and the Through Positive Eyes program continue?

Yes. Next stop: Seattle, at the Gates Discovery Center, in 2020. And we’ll see where the project takes us after that. We would like to tour the project for the next three years.

For a POZ interview with artivist D’Angelo Morrison, read “From Homeless With HIV to an Artist-Advocate With Hope.”

Priya, Mumbai, India, 2013

Priya, Mumbai, India, 2013

When I told my husband that I am HIV positive, he said, “How have you contracted HIV? Who have you been with?” And with these words, he left me. As soon as my parents heard about my illness, they abandoned me. I have four children, and they left me as well. People used to call me names. “She is diseased. Don’t go near her.” It was then that a lady came to me wanting to sell her goat, and I bought it for 2,000 rupees [less than $30]. I decided I would look after animals. The lady who sold me the goat didn’t realize it was pregnant, and six months later, it had a kid. Now I have three animals with me: Julie, Mariye and Shera. The four of us, we live as a family. My animals are my human beings. My family, my husband, my children have all betrayed me, but these animals have not. I was very nervous about taking photographs. I had never held a camera in my life. I remembered what they told me about the self-timer, so I thought I’d give it a go. I set up the tripod, attached the camera and set up the 10-minute timer. I went to lay my head on the pillow. Julie came to me, nudging me, and fell asleep in my arms. I held her. She pushed her head up, and the timer went off.

Christian, Washington, DC, 2012

Christian, Washington, DC, 2012

Soon after I was diagnosed, my mom told me she and my stepdad had been diagnosed HIV positive three months before. She just didn’t know how to tell anybody. We became really good friends and just went through it together, until she passed. I wish we had bonded earlier in life, but it was so good to have that family relationship at that time.

Gugu, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010

Gugu, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010

At school one day, the teachers [gave] the children an assignment, “Who is your hero?” When I was checking my daughter’s books, I saw that she had written about me, not Nelson Mandela. That’s why I love her so much. Sometimes I tell my daughter, “I will not die until you finish your school and your university.” In the meantime, I will stay strong. I’m not the dying type.

Ilsa, Mexico City, Mexico, 2008

Ilsa, Mexico City, Mexico, 2008

The first time I dressed as a woman, I felt I was another person. My gestures no longer provoked laughter. I don’t care any longer about the way others react. I am a person who matters.

Isaac, London, United Kingdom, 2015

I became HIV positive by having great condomless sex with somebody who was positive. Nothing more, nothing less. I just want to say to everybody out there, “If you have preconceived ideas about positive people, just forget them.” We are sexual beings with rights. I choose not to be stigmatized. I say pants-in-the-mouth to stigma.

1 Comment

1 Comment