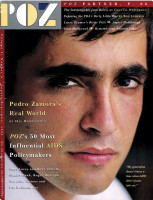

Pedro Zamora on the cover of POZ

Pedro Zamora was already an AIDS activist before he joined the cast of the third season of MTV’s The Real World. The reality TV show famously showed Pedro as he advocated for people living with HIV and struggled with his declining health. Pedro died of AIDS-related illness in November 1994 at age 22 just hours after the final episode aired.

Not only did the show depict one of the first openly gay men with AIDS in popular media, but The Real World also provided a platform for Pedro to share his romantic relationship with fellow HIV-positive activist Sean Sasser, who appeared on his own POZ cover in 1997. The Real World aired their same-sex commitment ceremony, considered the first such event ever televised. Sasser died at age 44 in 2013.

Titled “Pedro Leaves Us Breathless,” the cover story from the August/September 1994 issue of POZ—our third—was a Q&A with Pedro by renowned writer and pop culture columnist Hal Rubenstein. The interview explores how a Cuban-American boy from the suburbs of Miami became an AIDS activist. Below is an edited excerpt.

What made you want to be on The Real World?

I thought it would be a great way to educate people. One of the problems I face as an educator is that I can get up and tell my story about not feeling well or having fun, about getting sick or going out dancing, but people can’t really see it, and I thought being on the series would be a great way to show how a young person actually deals with HIV and AIDS. And I also thought, It’s four or five months in San Francisco—how bad could it be?

Did MTV express any reservations?

No. During the interview process, they voiced some concerns, but they were related to me and to my welfare. They told me it was going to be a very stressful situation, and they were worried about the toll it might take on my health. And we discussed that my six roommates should know that they are living with an HIV-positive person. But that was about it.

Why were you willing to risk the stress?

I thought about it, knowing that just being away from my family would be hard for me. But part of the changes I started feeling when I was diagnosed was my increased willingness to take risks. That may sound kind of odd, but I acquired this desire to experience things I hadn’t before. And it’s been very stressful at points. And during the filming, my T cells have dropped. And I got PCP [Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia].

How did your roommates treat you?

They knew one person in the group was HIV positive, but they didn’t know who. I told them the first night, and they asked a lot of questions; but there were questions about me, not the disease: “How did I feel when I found out?” “What did my family say?” Instead of “Can I get it from picking up a glass?” I was ready to answer that, but I didn’t have to, and that was very nice. They were pretty educated.

How do you handle having HIV?

Without a doubt, the hardest part of being HIV positive, of having this life-threatening virus, is that you can’t feel anything. You don’t feel sick. You don’t feel there is anything you shouldn’t be doing. Yet you’re supposed to plan your life around it. And think about life. The reality is, I’ll probably be dead in five years, but I try not to think about dying. But I do know the one thing I don’t want is a Cuban funeral.

Latinos, especially Cubans, will lay you out for two or three days, then have open house for 24 hours a day. It’s three in the morning and you’re surrounded by these 80-year-old ladies who haven’t seen you since you were 7, sitting around making jokes, amid all those ugly flowers, thousands and thousands and thousands of the tackiest flowers you’ll ever see.

A few months ago, I was at a CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] press conference, and they wanted to know why Latinos haven’t gotten it together. Why haven’t they heard the message? And I got annoyed.

I said that the reason we haven’t heard the message is that up until now we haven’t been called. The message had never been said in a way that we could understand or relate to, in a language we could make sense out of. None of it seems to be about us.

Take the simplest problem. It took us, what, 10 years to realize that you couldn’t find a pamphlet that wasn’t written for a white middle-class sensibility? Almost nothing was in Spanish and given out in communities of color. My reality as a young gay Latino man is very different than the reality of white America. That’s not necessarily bad or good. Just different.

How did you come out in Miami?

As far back as when I was 7, I can remember experimenting with guys my own age. I knew there was a difference. But it wasn’t until I was 11 that it clicked in my mind, “Yeah, I might be gay.” A close family member, I think it was my brother, was watching some guy on TV and blurted out the word faggot, and I connected it to what I was feeling. So I knew right away that it might not be accepted.

But I never went through the guilty feelings or the sense of being dirty that so many gays talk about. Somehow, I knew this is the way it was, and it was natural to me. I never dealt with it publicly until my mother died. I never told her, though I’m sure she suspected it, but I thought I would protect her. Now I go back and hear stories and realize that she wouldn’t have had a problem with it.

I was 14 when she died, and after that I didn’t care who found out. I told my father a few months later. I had met this guy who was 18 and we started spending a lot of time together. My father sensed something was odd, so I told him that I was gay. We talked for hours. He went back and forth between telling me it was a phase and then reciting a list of all the people in history whom he knew were gay.

It was like he was processing everything and was thinking it out loud, but it was pretty much the same when he found out I was HIV positive. He said, “You’re my son, I love you and nothing is going to change that.”

Tell us about Sean Sasser.

We met at the March on Washington [for LGBT rights]. I had given a keynote address at a conference that he attended, and he came up afterward and told me how much he liked it. He was an AIDS educator too.

Sean is the first HIV-positive person I’ve dated. And one of the things I loved was that when I first started talking to him, talking about my feelings, the changes in my body, how I react to the education, I could tell in his eyes, in his mouth, he knew exactly what I meant.

It’s harder because now I’m not only dealing with my disease, I’m dealing with his. I have this person whom I adore, and I now have to spend time thinking that he can get sick. Before, all the focus was on me.

I’m now in an intense environment, which makes everything in my life that much more important. I don’t have time to deal with bullshit, with games. I have to cut through things faster than other people. So does he. I’m not being cocky. I’m being efficient.

You credit this efficiency to having HIV?

Without a doubt. HIV has given me a lot of freedom.

[If you] say this is not acceptable in my life, I don’t want it, I don’t have room for it—if that’s what you’re bringing to the table—[then] I don’t have room for you either. It has given me the freedom to take more risks.

My life is being threatened every day. I’m dealing with AIDS, so I know I can deal with anything.

Comments

Comments