Artist Jack Walls, 66, was photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s boyfriend in the 1980s, until Mapplethorpe’s death from AIDS-related illness in 1989.

Since then, Walls has pursued his own art career, which he chronicles on Instagram. You can also see him in HBO’s 2016 Mapplethorpe documentary, Look at the Pictures, and read about him in Patricia Morrisroe’s 1995 biography of Mapplethorpe, which Walls despises.

A 1987 photo of Jack Walls by Robert MapplethorpeCourtesy of Jack Walls/Instagram

Now living in his native Chicago after decades in New York City and upstate New York, Walls recently gave an interview to longtime POZ contributing writer Tim Murphy for his Substack newsletter, “The Caftan Chronicles,” which runs monthly in-depth interviews with notable older gay men. Below is a short version of the long interview.

When did you move back to Chicago?

In 2019. Then came 2020, and the whole world shut down, and I’ve been living at my mom’s ever since.

What were your New York years like?

I first went to New York in 1974, when I was 17. I’d always had this obsession with it. My 7th grade teacher gave me Manchild in the Promised Land [a novel set in Harlem], then I also read Giovanni’s Room and Last Exit to Brooklyn—all before I was 15. The summer of 1977 I spent in Cherry Grove on Fire Island, which was gay heaven. This was pre-AIDS, so everyone was fucking like rabbits.

Was Cherry Grove more racially diverse than the [more posh neighboring gay beach community] the Pines?

No. My friend Peaches and I were two of the few Black guys. I know there’s racism in the gay community, so I took everything with a grain of salt. I was aware of derogatory terms like “dinge queens”—white dudes who were into Black dudes. And then some of these white queens would use the N-word.

In her 1995 biography of Mapplethorpe, Patricia Morrisroe details how much he used the N-word. Did that turn you off?

That book frankly is a piece of shit. When I met her, I detected that she was going to write a hit job. I never heard Robert saying “N this, N that.” Why would I put up with that? Everything he did was performative anyway. Black men—that was an aesthetic of his.

The first time you saw him, you said, “That’s going to be my boyfriend.”

No. When I went to his 1980 Black Males show, I said to my friend, “He’s gonna be my boyfriend.” Robert was not there.

Sorry. But what made you say that?

The photos were big and beautiful. I thought, This guy is fucking with these white art-world people. He’s shoving this shit down their throat.

You didn’t think it was exploitative or fetishistic?

Of course, it was fetishistic. I’m not stupid. That was the point. I’m an artist. I’m sophisticated enough to get it. I didn’t meet Robert until 1981, when we cruised each other on Bleecker Street, and then we kept seeing each other around. Finally, he gave me his card. So I called, and he asked, “Did you eat yet?” “No.” “Wanna meet at The Pink Teacup?” So I walk over, and he’s already sitting there. That was March 1982, and then we ended up together until he died in 1989.

A 2019 drawing by Jack Walls from his first Chicago showCourtesy of Jack Walls/Instagram

What was your relationship like?

Nice. Fun. Robert was working, and I was interested in his work because I was learning stuff about how to be an artist. He was 10 years older than me, and I respected that. Sam [Wagstaff, Mapple-thorpe’s benefactor and lover, who also died of AIDS] was 25 years older than Robert.

Let’s talk about the work you showed at the gallery WHAAM! In New York City recently. These are drawings. Do they resemble your previous work?

That’s like asking someone which of their children is prettier. All my work looks the same to me.

Did you feel freer as an artist after Robert died?

Well, he wasn’t going to be with me if I wasn’t going to be an artist. I’m a quick study. He and Sam liked that I could hold my own in a room.

How did you feel after both Sam and Robert died?

Basically, joy because they didn’t have to suffer anymore.

Are you happy being back in Chicago?

Yep. COVID was a blessing in disguise. People didn’t have anything to spend money on, so a lot of them started buying my art. I had my first one-man show at 50, and I’ve been selling art since then.

What were you like as a kid?

Ambitious. Even when I was in gangs, it’s because I thought I would one day write about it. Same thing with joining the Navy. My life—it’s been magical. Even through my years of junkie-ness. I’m healthy now. I’m not HIV positive.

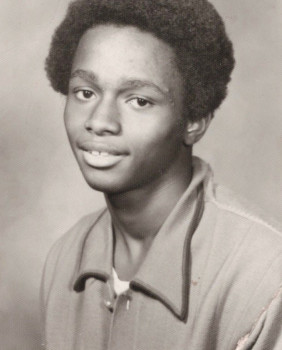

A photo of 14-year-old Jack WallsCourtesy of Jack Walls/Instagram

How did you avoid HIV?

If you were shooting dope, you didn’t share a needle. And [you didn’t have multiple sex partners]. I have to fall in love with someone’s brain first.

Do you miss New York?

There’s nothing to miss. Before, you had to be in New York. I used to go down to the piers. Those kids were wonderful, dancing the Hustle with those big boom boxes—the ones who ended up in Paris Is Burning. Angie Xtravaganza and I would dance salsa together.

What are you most proud of?

[Long pause] Honestly? My relationship with Robert. You wouldn’t be talking to me right now otherwise.

Was Robert in love with you?

I don’t know. You have to ask him.

I can’t.

Well, then, I guess we’ll never know.

Were you in love with him?

What do you think?

Well, he was your boyfriend, right?

Mm-hmm. Yep.

Do you miss him?

Yep. Every day.

What’s your biggest regret in life?

Watching my friends die from AIDS.

What do you want to prioritize for the rest of your life?

I just want to make art.

What about relationships?

I could never be in one. It takes too much work. [Pause] A lot of your questions—I didn’t want to give energy to some of the things you were bringing up [with the biography]. I wasn’t going to sit here and demonize Robert.

I wasn’t demonizing him. I was referencing how Morrisroe describes him.

Well, now you can reference what I said. “Oh, Robert used the N-word....” Nuh-uh, I wasn’t going down that path.

Why not?

I told you. I’m from the South Side of Chicago. I spearheaded [fighting] racism in the gay community. I was discriminated against by white queens. When you walked into gay bars back then, you never saw Black bartenders, so when I did my Boom Boom Room party [in Chicago in the 1990s], I told the bar owners that I wanted all the bartenders to be Black.

Anything I missed?

My mom used to talk to Robert on the phone. They got along great. Now, I overhear her bragging about her son Jack, the famous artist.

That must be a good feeling.

For years, when people would ask my mom “What does Jack do?” it was so nebulous. Once they realized I was making money, that’s all that mattered to them. When Robert was sick, some in the art world thought I would die of heroin or AIDS. Even I didn’t think I was going to make it past 30. But once I hit 35, I thought, I should start paying attention.

Are you proud you survived?

I’m proud that I’m still here and talking to you.

This article was excerpted with permission from The Caftan Chronicles by Tim Murphy.

Comments

Comments