I don’t know how many people walking into Madison Square Garden to see Madonna expected to cry, but I suspected I would—and I did.

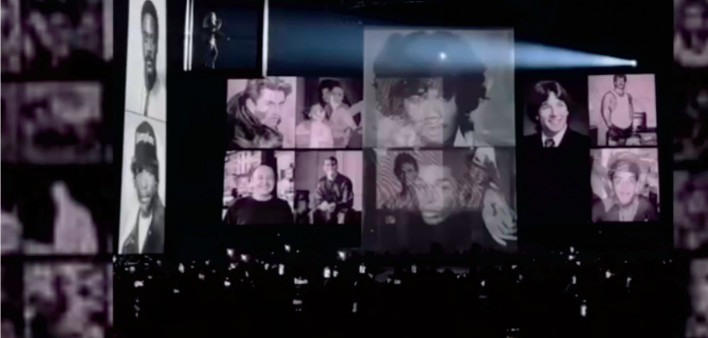

Prior to seeing the Material Girl on a New York stop of her Celebration tour on a chilly evening in January—postponed from sweaty August 2023 because the superstar fell ill and was hospitalized with a bacterial infection last summer—I read that she dedicated a portion of her performance to a sort of living AIDS memorial, where as she sang “Live to Tell” she flashed pictures of people she knew, such as her dance teacher Christopher Flynn and artist Keith Haring, who died of AIDS-related illnesses.

I walked up the many stairs and escalators to my nosebleed seat expecting to be moved by the tribute. When it came along, heralded by a background dancer falling to the floor and breaking what had been up to that point the joyous mood brought about by her early hits, including “Holiday,” “Everybody” and “Burning Up,” I did, of course, think of my father, who lived with HIV and passed in 2011. I thought about what it would be like to see his face plastered up on a screen alongside so many others. And I thought about what it meant that I conjured up his face in my own heart and about whom other people in the stadium might be thinking of at that moment.

Photos projected at the Madonna concert@theaidsmemorial/instagram

But that wasn’t the only AIDS-related moment of the night, nor was it the one that affected me the most. Later in the evening, during the dedicated time when the superstar, sporting a cowboy hat and a guitar over her shoulder, spoke directly to the hushed, rapt audience, she talked about her time in New York City during the early days of the AIDS crisis.

She pointed to two people in the audience she knew, nurses Ellen Matzer and Valery Hughes, who wrote the book Nurses on the Inside: Stories of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic, which was published in 2019, just months before the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world would once again be reminded of the importance of nurses.

“I’m here to give thanks to them for being at the front line of the AIDS crisis so many years ago,” Madonna told the crowd. “Thank you for your bravery and courage.”

She then talked about visiting the AIDS ward at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York’s Greenwich Village and how the ward was empty of people—no visitors—save the nurses caring for the sick at a time when nobody wanted to touch people with AIDS. Madonna thanked these women—whom she called angels and heroes—for doing their work. She also shared a story about seeing a young man in the AIDS ward, near death and no longer lucid, who believed that the woman visiting him was not Madonna but his own mother. She lay in bed next to him, and he said, “Mother, thank you for coming.”

Madonna spoke at length about nurses on another night during her New York stint, sharing that she had recently spent time in the hospital fearing for her own life and that the presence of nurses had kept her in good spirits as she faced her own mortality. The idea of Madonna and death in the same sentence feels anathema, since her four-decade-plus career in an industry that denigrates and discards female artists, especially those who make pop or dance music, has made her seem near-invincible. Her longevity has ossified into mythology, the way some people say that after the apocalypse, the only two things around will be cockroaches and Cher.

Madonna concert@theaidsmemorial/instagram

Madonna has spoken about her time in the hospital at other concerts. Many fellow concertgoers I spoke to considered her music career in the context of loss: the losses that marked the AIDS epidemic as well as the loss of her own mother, which she addressed at length in the documentary Truth or Dare and is the subject of several songs, including American Life’s “Mother and Father.”

Hearing Madonna speak about the power of nursing, I began to see her oeuvre as a dedication to mutual care and community. How much of her early music, including “Holiday,” are anthems about the power of a beat felt on the dance floor and the bodies and souls moving in rhythm with one another? Madonna’s discography can be viewed through a lens of loss, but what shifts when you choose to view it as a call to care for one another, to nurse one another?

Later in the evening, she sang “Mother and Father,” a song casual Madonna fans may not know. It’s the penultimate track on one of the singer’s least popular albums. When she sang it, images of her mother and her adopted son David’s mother, who died of AIDS-related illness, were projected above the stage.

At a time when we are revisiting the way tabloid magazines lampooned female pop stars in the 2000s, Madonna was using the stage to fight back against the narrative that her adoption of children from Malawi was motivated by paternalism and suggesting that perhaps it was more of a response to her own trauma related to the AIDS crisis, which Mary Gabriel describes in her Madonna biography, Madonna: A Rebel Life. Gabriel writes that Madonna’s visit to Malawi felt like “history repeating itself” and that she was moved to adopt children from the area because the visit reminded her of living in New York City in the early days of AIDS.

At the concert, I learned that Madonna held in equal regard the need to mourn the dead and the need to applaud those who care for the living. Although plans for a potential Madonna biopic have stalled, as I sat in Madison Square Garden, I thought maybe the milieu of the arena stage—in which Madonna is so at home—wasn’t cinematic enough.

Madonna had reminded the crowd that AIDS is bigger, more global, more diverse, more varied, more devastating, more personal, more all-encompassing than what many credit it for, something both universal and insular. When I walked out onto the sidewalk at 31st Street and Eighth Avenue, people were dancing to “Like a Prayer,” and I felt as though people had grasped the message; they were feeling together. We had, finally, gotten into the groove.

Comments

Comments