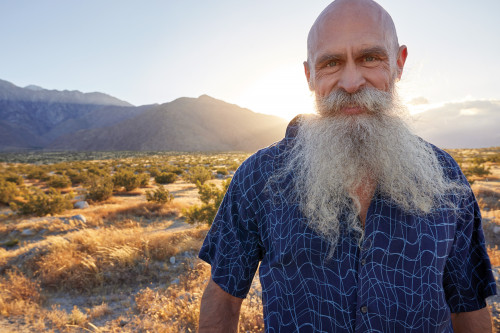

The alarm goes off at 5:30 a.m. Jeff Taylor, 57, rolls over to turn it off and finds himself staring into the face of Ivan, his rescue greyhound. Taylor realizes he has just enough time to feed Ivan and sip some green tea before his first conference call. As a full-time treatment advocate living in Palm Springs, California, Taylor has served over three decades as a community liaison for numerous research organizations and the Food and Drug Administration, HIV/AIDS groups, scientists, doctors and people living with the virus. In other words, he brings together diverse stakeholders so they can better tackle the latest HIV challenges.

Now that there’s effective treatment—at least for those who can access health care—what concerns do people with HIV face today, and how can a bunch of early morning conference calls possibly address them?

“Everyone is starting to recognize that we have what I call a ‘silver tsunami’ of aging HIVers who are going to overwhelm our care and service systems as the first generation to survive AIDS enters their 50s, 60s and beyond,” Taylor says. Indeed, as of 2015, nearly half of people with diagnosed HIV in the United States are 50 or older. By next year, the figure is projected to be more than 70%.

“But there’s very little in place to deal with this,” Taylor warns, noting that most services for seniors don’t kick in until age 65 but that people growing older with HIV are experiencing age-related health issues about a decade earlier than their HIV-negative counterparts. “We don’t have the infrastructure in place to address this,” Taylor says. “Most HIV research studies arbitrarily exclude anyone over 65—a relic from the old days when nobody was expected to live that long—so there’s a lot of catching up to do. We don’t know what happens as people age with HIV. It’s a huge unanswered question.”

And who better to answer this question than long-term survivors themselves? Since research often doubles as an incubator for policy, it remains critical that people aging with HIV are at the table to offer advice from the get-go.

At the prodding of advocates like Taylor, the research community is stepping up. For example, the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) recently launched an HIV and aging working group to explore the needs of this population, and Gilead Sciences, which manufactures several blockbuster HIV meds, funded a whole portfolio of related services.

But much more data are needed, and that means researchers need to be connected to older people with HIV. That’s where Palm Springs comes in. Members of the LGBT community, like Taylor, have been resettling and retiring in the area for decades. What’s more, thanks to a number of HIV clinics—including Desert AIDS Project’s medical clinic—the city offers a full array of HIV-related services. No wonder Palm Springs now boasts a concentration of older HIV-positive residents, many of whom participated in clinical trials in the early days of the epidemic as a way to access treatment and stay alive. (For a glimpse at this cohort, check out the 2015 documentary Desert Migration, which follows a day in the life of several gay long-term survivors.) This aging population knows firsthand the benefits of participating in HIV research—just ask Palm Springs resident and advocate Timothy Ray Brown, aka the Berlin patient, the first and only person to be cured of HIV.

Data from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program show that more than 10,000 people in Riverside County—home to Palm Springs—are living with HIV, mostly in Coachella Valley and the eastern part of the county. Of note, 78% of all people living with HIV in Palm Springs and the surrounding cities are over 50 years old, 40% are over 60, 10% are over 70 and 1% are over 80; a number of individuals are in their 90s.

For scientists and advocates like Taylor, this represents a chance not just to research the needs of long-term survivors but also to offer them care, treatment and social networks. The primary way to tap this amazing resource is the HIV+Aging Research Project—Palm Springs (HARP-PS). Launched in 2015, the project describes itself as “a community-based, community-supported coalition of health care providers, people living with HIV, their advocates, their families and friends. Our overarching objective is to enable long-term survivors to live well despite their chronic HIV infection.” Taylor serves as the project’s executive director. HARP-PS also spearheads the popular Positive Life Series, monthly evening seminars about HIV-related topics that include a free meal and American Sign Language interpretation. [Editorial disclosure: POZ’s Jennifer Morton recently joined the board of HARP-PS.]

“This coalition, spearheaded by Jeff, has been instrumental in bringing together health care providers, people living with HIV and advocates to develop community-based research that will improve the quality of life for long-term survivors,” notes Jill Gover, PhD, the director of the Scott Hines Mental Health Clinic at the LGBT Community Center of the Desert.

Over the years, treatment activists have worked diligently and with little fanfare to make a collaboration like HARP-PS possible and to ensure that long-term survivors remain a crucial and vocal element of the research process.

To date, HARP-PS has identified three HIV research priorities for the aging population: cognitive function and memory loss; depression and isolation; and inflammation and related comorbidities. HARP-PS occasionally conducts its own research—mostly psychosocial since it’s not a brick-and-mortar clinical research site—but it primarily collaborates with academic researchers in the region (University of California programs in Los Angeles, San Diego and Riverside, to name a few) and across the nation, connecting researchers with the Palm Springs HIV community.

Last year, for example, HARP-PS teamed up with Michael Plankey, PhD, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, to create a snapshot survey about resilience—examining the attributes that lead some folks to thrive with HIV while others struggle—that was rolled out in the Palm Springs community. (More about those survey results later.)

“We’ll happily partner with anybody anywhere,” says Taylor, adding that “aging with HIV is not just a Palm Springs problem—it’s a national and global phenomenon,” which is why HARP-PS is working to post the survey online so anyone can access it. “The more data we can get,” he notes, “the better.”

Matt Sharp, Jeff Taylor and Gregg CassinJennifer Morton

Jeff Taylor, Erin Doty and Chris ChristensenCourtesy of Jeff Singer

A ONE-MAN STUDY OF RESILIENCE

In many ways, Taylor’s own history with the epidemic and treatment research is typical of many long-term survivors. Originally from Iowa, he headed to the University of Chicago to major in Japanese in the mid-1980s, just as AIDS was devastating Boystown, the heart of Chicago’s gay community.

Although he suspected he was HIV positive at the time, Taylor didn’t get tested right away. “I purposefully waited until there was some therapy or hope,” he says, “and at the time, that was AZT,” referring to the first HIV med, which was approved in 1987. He got tested in 1988.

“The first thing I did after getting my positive diagnosis/death sentence,” he says, “was to research available trials.” He signed up with what’s now called amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, to receive a catalog of clinical trials. “The listing,” he recalls, “came in a plain brown wrapper, like it was porn or something.” He also attended community meetings about HIV therapies that were organized by what later became TPAN. By the end of 1988, Taylor was enrolled in ACTG 019, a randomized, double-blind study of AZT (Retrovir or zidovudine) monotherapy. Turns out, he got the placebo. In retrospect, Taylor says, he was lucky because the original dosing in the trial was toxic.

Nonetheless, he views that period as “a very positive experience,” a time when the gay community helped its own through research and altruism. “There was this galvanizing sense of ‘we’re all in this together’ given the horrific stigma, the genocidal policies of the Regan administration, etc. Certainly, the research community’s attitude and dedication were very inspiring and made me want to do whatever I could to help that effort.”

Adding to the motivation was the fact that they saw results. “The advances,” he says, “were coming fast and furious—at least in terms of preventing opportunistic infections.”

But the brutal Chicago winters took their toll on Taylor’s compromised immune system, leaving him with sinus infections the entire season. (Remember, modern lifesaving HIV treatment didn’t arrive until 1996.) And hitting the books and working full time as a ward clerk in a neonatal intensive care unit at the university hospital didn’t help. He’d get sick pulling all-nighters, and fatigue became constant.

When he came out as gay to his parents, Taylor recalls, “they stopped paying my rent because they ‘wouldn’t support my lifestyle.’” Something had to give. Worried that another winter would kill him and watching his friends die around him, Taylor moved to sunny San Diego in 1989.

He became involved with the ACTG trial site at the University of San Diego under renowned virologist Douglas Richman, MD. Taylor also helped start their local community advisory board (CAB) for HIV research and joined the national CAB, now called the Community Scientific Subcommittee. The experience was critical to his activism. He attended national meetings, learned about the numerous HIV research programs at the National Institutes of Health and had a front-row seat as early AIDS activists fought their way into ACTG meetings.

“They were a fractious group,” Taylor recalls. “I’ll never forget the first meeting I attended where people were screaming at each other, and one stormed out of the room knocking over some chairs on his way out. I asked one of the cochairs—a preternaturally calm mother figure named Allegra Cermak, who is the community coordinator for ACTG to this day—‘Was it always like this?’ She responded, ‘Oh, it’s much better than it was—they used to throw the chairs at each other.”

Taylor’s involvement in research advocacy became more specialized as it grew. He joined the AIDS Treatment Activists Coalition, a national volunteer group that advises the pharmaceutical industry in the United States and Europe on research and clinical trials. And while he served on the national CAB, the issue of body-fat redistribution emerged as a problem for people on HIV treatment, so he helped found the Lipodystrophy Subcommittee to research the issue.

These experiences served him well in the late ’90s when he faced another health crisis: anal cancer. He had been diagnosed with anal herpes years before, but it had resolved once he got on HIV treatment and his immune system recovered. When problems resurfaced, he researched the topic and came across Joel Palefsky, MD, a preeminent expert on diseases related to human papillomavirus (HPV), a common cause of anal, cervical and oral cancers.

At the time, Palefsky recommended that people at risk get anal Pap smears. Taylor asked his own doctor about this and was told the lab wouldn’t process a sample from a man. Instead, Taylor had to endure several biopsies and was eventually diagnosed with Bowen’s disease, a slow-progressing skin cancer typically seen in elderly men. His doctors didn’t want to remove it. Taylor insisted. The docs held firm.

So, armed with the lessons of self-empowerment, Taylor found a surgeon in Los Angeles who, using laser surgery, successfully removed the cancer as well as scar tissue from the botched biopsies.

That ordeal inspired him to become involved with the AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC), a global clinical trials group focused on HIV-related cancers and supported by the National Cancer Institute. Palefsky founded AMC’s HPV Working Group, and Taylor teamed up with him to develop the Anal Cancer/HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) Study.

“Jeff has been a great ally,” Palefsky tells POZ, “a steady and determined supporter of research on prevention of anal cancer and a tremendous advocate for greater education and access to prevention services for the LGBTQ community.”

One of AMC’s goals, Taylor says, is to make anal Pap smears a standard of care for anal cancer prevention just as it is for cervical cancer prevention. As Taylor puts it: “It’s the same virus, the same type of cells infected, just a different location.” But insurers won’t cover anal Pap smears unless they are proved effective in a large, randomized clinical trial—which translates to a 5,000-person five-year trial costing more than $90 million, an endeavor beyond the scope of anything AMC had undertaken. The good news? With Taylor’s and Palefsky’s perseverance, the ANCHOR study is now a reality. The trial is currently under way at more than 20 sites nationwide (to enroll, visit AnchorStudy.org or call 844-HIV-BUTT).

Jeff TaylorAri Michelson

VITAL LONG-TERM SURVIVORS

Taylor now brings his results-oriented research advocacy to long-term HIV survivors living in the Coachella Valley and, ultimately, across the globe.

Taylor began visiting Palm Springs as a tourist. But in the late ’90s and early 2000s, he noticed that the city was transforming from a “burned-out spring break destination under Sonny Bono”—the city’s then mayor and, yes, also Cher’s famous ex—“and becoming an up-and-coming trendy destination renowned for its mid-century architecture.” Smitten, in 2001, Taylor made the city his new home.

“Of course,” he says, “it was gay men priced out of San Francisco and Los Angeles who thought they were going to die or who were leaving stressful careers and cashing out of their San Francisco homes in the tech boom who moved to this sleepy little resort town and started buying and fixing up these houses, and, as we always do, we started a gentrification trend.”

The snapshot resilience survey HARP-PS conducted last year offered a more detailed picture of the local long-term survivors. It found that they had been living with HIV an average of 30 years (with a range between 10 and 40), that 95% reported an undetectable viral load; 70% were college graduates; 50% lived alone; 60% were single; and 65% reported having factors that increased their resilience (these include experiencing less anxiety and depression, enjoying more companionship and having a pet).

An interesting sidenote on research into long-term survivors: The HARP-PS survey was pioneered at the national Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), which was founded in 1984 and to this day follows men who have sex with men who are living with or at risk for HIV. Recently, MACS combined with its female counterpart, the Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS), to form one cohort.

Over the years, so many MACS participants have ended up in the Palm Springs area that MACS’s Los Angeles–based researchers travel to them rather than have the men visit the LA site each month. And Taylor is advocating with researchers to enroll more “old-old” survivors—people in their 70s, 80s and 90s.

Taylor acknowledges, though, that in many ways the HIV population in Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley lacks diversity. “We’re always looking,” he says, “to seek out underserved populations, like people of color, women, the growing trans community and the woefully underserved HIV-positive deaf community.”

That doesn’t mean that Taylor and others collaborating with HARP-PS haven’t made progress in understanding aging and HIV. “What we’ve learned from our focus groups,” Taylor says, “is that it’s the isolation, depression and emotional and mental health issues that keep people from taking care of themselves and just being happy. AIDS Survival Syndrome [ASS, a form of posttraumatic stress disorder] is real, and we need to address it.”

That’s a challenge, he says, because when effective treatment arrived, most HIV-related health programs, like Ryan White, switched their focus from providing quality of life services to simply getting people on meds.

To further its own research—primarily on isolation and depression, “the biggest unmet needs,” in Taylor’s words—the HARP-PS team has applied for several grants from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), a nongovernmental effort that’s part of the Affordable Care Act and funds research to help people make better health care decisions.

Two projects already funded and under way include the Obesity and Healthy Thinking Study, which aims to show whether Egrifta (tesamorelin, a drug that stimulates the release of human growth hormone and is already approved for other uses) may improve brain function, and the ANCHOR study. (To learn more about these and future studies, visit HARP-PS.org.)

“One project on our wish list,” Taylor says, “is to work with existing pet programs for people living with HIV to evaluate how pets improve quality of life. Quantifying this would help justify funding for programs that place pets with people and help subsidize their care, as a vet bill can prevent people on fixed incomes from keeping a pet.”

Once again, more research is needed. The good news is that it’s forthcoming, thanks not only to scientists and advocates like Taylor but also to people aging with HIV who share their own life experiences and voice their concerns.

Decades into the epidemic, resilient long-term survivors continue making vital contributions to the HIV community. They are leaving a legacy of willpower, intellect and guts for future generations to come.

17 Comments

17 Comments