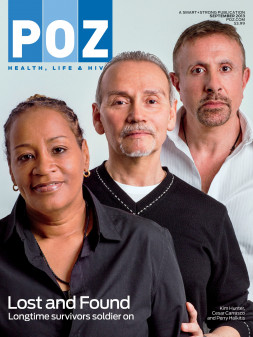

The life story of Cesar Carrasco, a 58-year-old Chilean-born New Yorker, tracks the larger story of living long-term with HIV/AIDS. Carrasco was an undocumented newcomer to the United States in 1984, working as a handyman, when he got HIV. Like many in that early era, he turned to the newly formed Gay Men’s Health Crisis for support, soon pitching in as a volunteer. He also got his green card and went to college.

A few years later, he recalls, “I felt that being a nice and pleasant homosexual who helps others die in peace just didn’t cut it anymore.” So, like many in that late-’80s moment, he joined the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) ?becoming a member of its Latino caucus. “That helped me channel my frustration and rage at the government,” he says. “We were a close group, always getting arrested. For several years, we enjoyed good health.”

Between then and 1993, Carrasco watched his CD4 count plummet to 20, and yet he outlived some of his closest ACT UP friends. By that time, the once-mighty New York chapter of ACT UP, which had powered so many effective demonstrations, had quieted down. Still healthy, Carrasco took a gamble on his future and went back to school for his social work degree. He earned it in 1996, the very year that new drugs called protease inhibitors emerged and began saving lives.

Carrasco took the meds—and got sicker than ever from the side effects. “Kidney problems, fatigue, insomnia, nausea,” he recalls. “I was a basket case.” So much so that he had to take a sick leave from his new job. He didn’t return to work until a med change in 2002 made it possible.

He’s been working ever since as a hospital social worker, and his health and finances are largely solvent. But something isn’t quite right. It’s not that Carrasco has ever fallen into the kind of crippling depression or drug use that has earned headlines in the past decade for some of his fellow activist alumni. It’s just that, for someone who cheated death, Carrasco isn’t very happy.

He’s been working ever since as a hospital social worker, and his health and finances are largely solvent. But something isn’t quite right. It’s not that Carrasco has ever fallen into the kind of crippling depression or drug use that has earned headlines in the past decade for some of his fellow activist alumni. It’s just that, for someone who cheated death, Carrasco isn’t very happy.

“My personal life sucks,” he says. “I can’t manage having to disclose my HIV status in a gay community where everybody is supposed to be negative. I’m not sure that I really care about or am capable of sustaining a relationship. I haven’t been able to build a satisfactory social life. I’m getting older. I feel like a Martian on the planet Earth, but nobody knows I’m from Mars.

“Professionally,” he continues, “I feel very fulfilled, but I feel shell-shocked or in a cocoon in a deep, receded way. It’s not something that manifests in outbursts of anger or drinking too much.”Carrasco sighs, searching for the right words. Finally he says, “I’m just kind of nowhere.”

He isn’t alone. In an era when HIV is often treated with one pill a day and much of the gay community, and the country, has turned its attention from AIDS to marriage equality, Carrasco and his fellow long-term survivors have effectively become part of a shadow population.

Having lived with HIV/AIDS for 25 years or more, they went through the very worst years of the U.S. epidemic, often outliving multiple loved ones and awaiting their own demise. Now that they’re miraculously middle age, they find that in a post-protease culture both their tremendous losses and their hard-won victories have been (often willfully) forgotten.

They’re called “The AIDS Generation” by Perry Halkitis, PhD, MPH, a 50-year-old New York University psychologist. He’s also the author of a book by the same name that contains in-depth interviews with 15 gay men in this peer group. Halkitis, diagnosed with the virus in 1988 but by his own calculation HIV positive since 1981, is a member himself of this generation. He estimates the group, which not only includes gay men, but also women, straight men and transgender people, is only about 50,000 people nationwide—just 5 percent of the million-plus Americans living with HIV.

“We’re grappling with memories while trying to move forward,” Halkitis says. “For anyone entering middle age, you’re trying to make sense of your life and figure out your legacy. But for us it’s more complicated because of the unnatural deaths we experienced at an early age, the feelings of hopelessness for our own lives. And a lot of us now feel hugely isolated, unnoticed and unheard.”

Halkitis is echoed by Peter Staley, 52. The founder of AIDSmeds was diagnosed with HIV in 1985 when he was a 24-year-old New York stockbroker, but he soon became one of the leading members in ACT UP and the Treatment Action Group (TAG). After his activist heyday died down in the late ’90s, he fell into career despair and crystal-meth addiction before entering recovery and reemerging as an advocate for gay male survivors of the AIDS crisis.

“We’re in middle age now, with physical issues,” Staley says. “At the same time, we’re often haunted by the past. We’re the generation that fought hard for our lives, and now we’re the walking wounded. We’ve faded into the woodwork and watched the world move past us. Some of us have found our way again, but many of us feel pretty lost.”

“We’re in middle age now, with physical issues,” Staley says. “At the same time, we’re often haunted by the past. We’re the generation that fought hard for our lives, and now we’re the walking wounded. We’ve faded into the woodwork and watched the world move past us. Some of us have found our way again, but many of us feel pretty lost.”

A survey of nearly 1,000 New Yorkers age 50 and older living with HIV for an average of 13 years, done by the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America (ACRIA), found that two-thirds called themselves moderately or severely depressed—more than five times the rate of depression in that age group in the general population. “We saw very high lifetime and current rates of substance use, particularly alcohol use,” says Mark Brennan-Ing, PhD, a study leader, “as well as very high levels of loneliness, social isolation and stigma.”

The good news? Recent events suggest that, after 15 years of relative silence both from and about the epidemic’s oldest survivors, a public reckoning of sorts is taking place—one that’s both processing the events of the past and asking what the crisis’s longest survivors needs are going forward.

Recent documentaries have looked back on AIDS and AIDS activism in the 1980s, including Vito (about the late activist and author Vito Russo) and We Were Here (about patients and caregivers in San Francisco). United in Anger, by Jim Hubbard, and the Oscar-nominated How to Survive a Plague, by David France, both mined reams of archival video to weave together powerful stories of the rise, triumphs and eventual decline of ACT UP New York.

“It’s like the Vietnam War,” says Staley, who is heavily featured in France’s film. “It was too painful to immediately revisit, and it took about 15 years before there was a wave of looking back.”

Sadly, it was the 2012 death of Spencer Cox, 44, another HIV-positive activist centrally featured in Plague, that has spurred much recent action around the lives and needs of longtime AIDS survivors. Like Staley, Cox contracted the virus and entered ACT UP young, then also lost his way and began using crystal meth after the protease era. In the mid-2000s, he founded the Medius Institute to research the needs of gay men in middle age, but a lack of funding kept him from getting far with it. After an extended period not taking his HIV meds, he died of AIDS-related causes.

“I feel Spencer was a kind of victim of the epidemic’s aftermath,” says Carrasco, echoing a sentiment that exploded online after Cox’s death. That virtual grief funneled its way into a live evening forum in New York City in May that brought together hundreds of people, including representatives from more than a dozen HIV/AIDS and LGBT groups, for three charged hours of discussion by, for and about epidemic survivors.

It was organized by the Medius Institute, which Staley and other friends of Cox have revived in his memory. “We’re going to be following up,” Staley says. “We’ve gone from a time when there was a tremendous sense of community to one now where there’s a stunning lack.”

Meanwhile, at Columbia University, longtime HIV-specializing psychology professor Judith Rabkin, PhD, MPH, is organizing a study along with TAG comparing aftermaths of people who were involved in ACT UP in the ’80s with people who were not. “Many have crashed and burned, but many have survived and thrived,” Rabkin says. She hopes the study can yield insight into both the benefits and challenges of engaging in activism versus not.

Would she call what some AIDS veterans have experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? She ticks off a number of clinical criteria for PTSD that have been observed in military veterans—exposure to death or the threat of death, with reactions including fear, helplessness or horror—but then concludes: “I think it’s more chronic stress that people were exposed to because of AIDS,” she says. “The question is: Are there lingering effects?”

Focusing only on the beating the AIDS Generation has taken would, of course, be telling just half of the story. The other half involves the tremendous resourcefulness and strength that many people in this group have manifested over the years—the ability to continue on and even flourish amid overwhelming loss and anxiety. It’s called “resilience” in clinical terms, and only recently has it become a hot topic among researchers.

“A lot of these people were told they were going to die a painful, terrible, stigmatizing death—and soon,” says Ron Stall, PhD, MPH, a University of Pittsburgh professor who has turned the focus of his work with middle-age gay men, many of them HIV positive, from cataloging their vulnerabilities to pinpointing their sources of strength. “There were no legal protections, and people like [former U.S. Senator] Jesse Helms went out of their way to kick them when they were down. But gay men never ran. They took care of their sick and fought for their rights.

“But now,” he continues, “some of those survivors are getting older and having a hard time keeping up that extraordinary fight, which makes sense.” At the same time, he notes, “there’s also a group that’s thriving and doing well.” Stall awaits funding to continue studying what factors nurture resilience. He says so far it seems clear that connection to community, family ties (either biological or, as has long been the case among LGBT people, created) and, often, continued activism or volunteerism confer strong protection on HIV-positive long-term survivors.

These factors certainly aren’t limited to gay men. For instance, take Kim Hunter, 51, of New Jersey. A former heroin addict, Hunter was doing prison time for robbery when she learned she was HIV positive in 1988. “There was a period during my incarceration when people were dying of AIDS and not acknowledging the disease,” she recalls. “They were getting sick and passing away, and it was just everywhere. I thought I’d die because everyone else was. Eventually I had to ask myself, ‘Why am I still here?’”

These factors certainly aren’t limited to gay men. For instance, take Kim Hunter, 51, of New Jersey. A former heroin addict, Hunter was doing prison time for robbery when she learned she was HIV positive in 1988. “There was a period during my incarceration when people were dying of AIDS and not acknowledging the disease,” she recalls. “They were getting sick and passing away, and it was just everywhere. I thought I’d die because everyone else was. Eventually I had to ask myself, ‘Why am I still here?’”

When she was paroled in 1998, she decided to help other women in her shoes. She got her GED, a BA in human services and eventually became a Certified Alcohol and Drug Counselor at New Jersey’s Hyacinth AIDS Foundation, where she remains today. For her, resilience has come through daily acceptance of things as they are, or what she calls “life on life’s terms.”

She adds, “I try to stay motivated and focused. Having some day-to-day normalcy has worked for me—getting up and going to work, family support. Years ago people never depended on me for anything, but over the years I’ve become the go-to person in the family and with my clients and friends.”

One of her goals is a support group for longtime HIV-positive women because they have specific needs. “When I talk to my new clients about how the epidemic was, they’re clueless.”

Resilience, which can include constant openness to new forms of help, is also key to the survival of Phyllis Marks, 70, who lives in New York City’s East Village. A retired social worker, Marks got clean from heroin addiction in the rooms of various 12-step programs in 1980, but then learned she was positive in 1986. By 1990, she had zero CD4 cells and was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, an AIDS-related cancer, which she beat with chemotherapy.

Among fellow recovering addicts and in support groups at the Center for Living, where people with AIDS flocked in the 1980s for nutritional and spiritual support, death was all around her. “Three of my friends would die in a week, and there I was,” she says. “I didn’t know how to deal with the grief.”

Instead, Marks tried every source of survival she could get her hands on. “Acupuncture, all kinds of holistic stuff, lecithin ice cubes, urine therapy, B12 shots, every form of meditation possible,” she recalls. Marks made it to the protease era, but there was an emotional toll. “For a long time I didn’t get close to people because I was afraid I was going to lose them. These are things I don’t really talk about now.”

She recently lost one of her few remaining friends from the Center for Living era. “There are three of us left now out of 200.”

Today, says Marks, resilience still comes in the form of her morning 12-step meeting, where she has a longtime crowd of friends, positive and negative, who know her whole story. Sustenance also comes from remembering the intense camaraderie of the crisis years. “We were all on a sinking ship together,” she says. Even amid death, “there was so much healing that went on at that time.”

Can longtime survivors get back to that place where everyone is in it together? In New York, one offshoot of the ACT UP documentaries and Cox’s death is that ACT UP veterans have begun organizing regular reunions—the first one took place in July. (Go to actupnyalumni.org to learn more.) For those who weren’t there the first time or for the less politically inclined, groups like Strength in Numbers, which organizes social events for HIV-positive gay men, have chapters in several cities.

“We need to focus on celebration,” Halkitis says. “We need to be getting awards for what we’ve lived through. We need a place for this generation where we become the elder statesmen of the community, where we are revered. It’s beginning to happen.”

Perhaps it may happen for Cesar Carrasco. Isolated for so long now, he says he’s gone back to therapy. “I was staying home alone, not wanting to talk to anyone. And I said to myself, ‘You’re digging your own grave.’” He may even take painting classes—and hit some of the reunions of ACT UP, the group of fellow travelers that sustained him through his years of greatest loss.

“I’d enjoy joining that,” he says. “Not just for comfort, but for understanding what’s going on with all of us today.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated.

40 Comments

40 Comments