In 1991, as the United States was battling the AIDS epidemic, the country was fighting another enemy abroad. Many front-yard trees were decorated with yellow ribbons in recognition of U.S. military members deployed in Iraq during the Gulf War. Struck by the sight of so many ribbons while driving in upstate New York with his partner Harvey Weiss and artist Frank Moore, costume designer Marc Happel wondered whether a ribbon could be used as a symbol to acknowledge the HIV epidemic.

That night, Happel, Weiss and Moore attended a meeting of the Visual AIDS Artists’ Caucus—a group of artists who’d come together to raise AIDS awareness—and pitched the ribbon idea. The caucus had wanted to create a meaningful symbol to show support and compassion for those living with and affected by HIV and AIDS. They settled on a simple red ribbon that could be folded and pinned onto a lapel or neckline. The group chose the color red to symbolize not only blood but also passion—both anger and love. A local ribbon supplier donated spools of red ribbon, and the artists hosted “ribbon bees” to fold and pin thousands of ribbons to a small informational pamphlet for distribution.

A Visual AIDS red ribbon bee. From left: Dieter Hall, Ira McCrudden, Joanna Thornton, Marc Happel, Toby Bochan, James Morrow, Allen FrameCourtesy of Visual AIDS

In mid-May, the group collaborated with Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS on an ambitious idea: to get actors to wear the red ribbon onstage at the upcoming Tony Awards. After all, the theater community had been hard hit by. With only a few weeks to do so, the groups used their myriad theater world contacts to get the ribbons into the hands of those who would be dressing the stars that night.

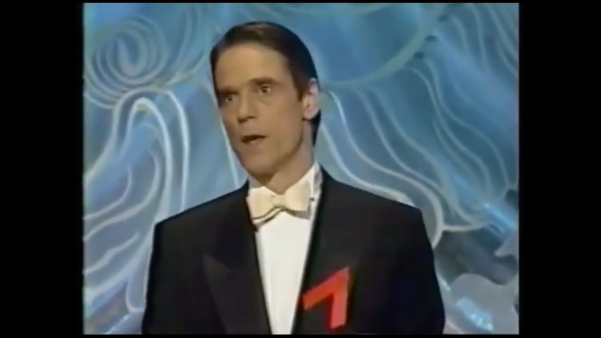

On June 2, the night of the 45th Annual Tony Awards, the Visual AIDS artists watched the Tony telecast in suspense. Would anyone be wearing the ribbon? The answer turned out to be a resounding yes. Host Jeremy Irons was the first person onstage wearing it, and he was followed by many other presenters and winners throughout the evening, including Daisy Eagan, Tyne Daly, Kevin Spacey, Joel Grey and Penn & Teller. But no one onstage explained its meaning, which gave rise to a media frenzy the next day.

Suddenly, the red ribbon was a thing. It was soon seen at all the major Hollywood award shows, worn by everyone from Jamie Lee Curtis and Whoopi Goldberg to Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Pryor. The ribbon became a way for folks to show their support for people living with HIV and AIDS and to advocate for resources to end the epidemic, and it was the perfect conversation starter.

In a May 1992 New York Times article titled “The Year of the Ribbon,” Mark Carson, a magazine editor living with AIDS wrote: “People come up to me and ask me how to get one. I laugh and say, ‘Go to Woolworth’s.’ But I’m glad they ask. At the deli two months ago, this woman said: ‘Why do you wear that?’ And I was able to explain. It feels good to say the word AIDS out loud, not in a shameful way, not in a hushed tone, but as something we all think about and share with the rest of the world.”

But some activists disparaged the ribbon as a shallow way of signaling AIDS solidarity without having to do any real work. In the same article, ACT UP member Ann Northrop said of the ribbon: “I wouldn’t be surprised to see [President George H.W.] Bush himself wear one someday—that’s how banal it’s become. The element that is missing in the ribbons is anger. People can be sympathetic from here to sunset but that won’t stop a quarantine.” (In 1992, politician Mike Huckabee had suggested that people with AIDS be quarantined.)

Over the coming decade, the red ribbon would become ubiquitous. Visual AIDS chose not to copyright the red ribbon because it wanted it to be widely used.

“What we wanted to do,” Happel said in an article on The Body.com, “was create something that a mother in Michigan could wear on the lapel of her blouse, and you know maybe her son was living in New York and living with AIDS, and she wanted to do something. I think it was just, it was also a symbol that we created that, that somebody could wear, and somebody might go up to them and say, ‘What is that? Why are you wearing that red ribbon?’ And hopefully that person would say, ‘Here’s why.’”

For a time in the’90s, the red ribbon reigned supreme on the red carpet. In 1993, the United States Postal Service even issued a 29-cent red ribbon stamp.

iStock

Said Patrick O’Connell, who served as the Visual AIDS director at the time, “People want to say something, not necessarily with anger and confrontation all the time. This allows them. And even if it is only an easy first step, that’s great with me. It won’t be their last.”

In subsequent decades, as the advent of effective treatment contributed to the evolution of HIV from a death sentence to a chronic manageable illness, the visibility of the ribbon waned. But its significance as an international symbol in the fight against AIDS has not diminished, and it continues to be used by HIV organizations around the world to raise awareness and spark conversations about the virus. In 2015, the red ribbon was added to the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

1 Comment

1 Comment