In 2001, Kory Montoya, now 42, quit his job without giving notice. He walked out of the Seattle clinic where he worked with the developmentally disabled, packed his bags and bought a one-way train ticket—heading for the Jicarilla Apache reservation in desolate northern New Mexico, where he grew up. Montoya, who is Native American, had lost touch with his mother and five siblings. His mom severed all ties with him after he came out as gay in a letter he sent her in the early ’90s—and as HIV positive in another letter, which he sent in 2000, nearly a decade after his diagnosis. Still, Montoya was determined to reconnect with his family. “I decided that I missed [them],” he says. “When I was up in Seattle, I met people who were positive, and their families accepted them and were there for them.”

Having finally arrived back home at the reservation, he walked up to his childhood porch. His mother answered the door—and, Montoya says, shut it in his face. He lugged his bags back out to the remote highway and hitchhiked to Albuquerque, three and a half hours away.

Montoya knew almost no one there, so he made his way to an HIV prevention meeting for Native Americans. “That’s where it all started,” he says. “I kept doing my homework and finding out the statistics of Native Americans living with the disease and finding that nothing is being done. There was no voice. So I decided to go out there and stand up.”

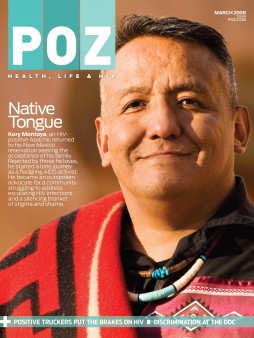

Today, seven years later, Montoya, who is 5’10" and has short-cropped black hair flecked with gray, travels the state visiting reservations, schools and substance-abuse centers to tell his story. He also sits on the Community Advisory Council of the National Native American AIDS Prevention Center; was appointed by New Mexico governor Bill Richardson to his HIV and AIDS Policy Commission; is a member of the New Mexico Community Planning and Action Group; and, this past spring, took the position of interim executive director at a New Mexico AIDS service organization. “Kory is totally devoted,” says Steve Garrett, also an Apache and Montoya’s predecessor at the organization, who was diagnosed in 1982. He helped mentor Montoya in AIDS advocacy. “In the past year,” Garrett says, “he’s really evolved and now totally gets [activism].”

The Native American AIDS community needs Kory Montoya. HIV rates in American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian communities are estimated at 11.5 per 100,000, 40 percent higher than the Caucasian equivalent. Indeed, amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, reports that Native Americans have the third-highest HIV-infection rate in the United States, after African Americans and Latinos. The rate may be even higher: Native Americans are often defined as “other” in surveys and did not get their current, most accurate U.S. census category until 2000, making any stat involving them hard to tabulate. “We are wary of letting people onto Native lands to take a head count,” Garrett says. “It goes back to when Europeans first entered this country. I mean, do you trust the U.S. government?”

Stigma and lack of HIV education deter testing among Native Americans (as they do among many other marginalized racial communities), and many Native people are not diagnosed until they have progressed to AIDS. The majority of Native peoples depend on Indian Health Services (IHS) for care, but the IHS budget meets only 50 percent of estimated need, and Native Americans get 40 percent fewer federal health funds per capita than any other group, including prison inmates. According to Charlton Wilson, MD, associate director of the IHS-funded Indian Medical Center in Phoenix, “HIV is near a tipping point in Native communities.”

Montoya’s journey with HIV began in 1984, when he enlisted in the U.S. Army, at the age of 18. After a three-year stint as a clerk in Germany, he was dishonorably discharged because of his sexual orientation; he left the service without even pausing to set up his veterans’ benefits. After spending the next three years wandering around the American West, he settled in Seattle in 1991. “I liked Seattle,” Montoya says. “I didn’t feel like living on a reservation. And I don’t think that I would have been accepted there [as a gay man].” Shortly after his arrival, he tested positive for HIV.

These days, whenever Montoya addresses reservations about his status, hoping to fight stigma and homophobia, he often has Marie Kirk, the HIV coordinator for the Albuquerque Area Indian Health Board, by his side. “I do basic AIDS 101, then he shares his personal story,” she says. “We have 23 tribes in New Mexico, and 19 are not getting [any] HIV prevention education.” She adds that often only a few people show up at their reservation workshops. The reasons, she says, include insufficient prevention funds and an aversion to talking openly about personal issues, such as sex and substance abuse, which often fuel HIV infection. She says Montoya’s experience with his family is far from unique: “They don’t want shame to be brought on the family unit. Instead of being up-front and saying, ‘This is what my kid has,’ they wonder, ‘What will people say?’”

Indeed, in many Native American communities HIV is just another challenge to pile upon an overwhelming litany of social and health problems. Compared with other racial and ethnic groups, Natives have higher rates of poverty and STDs like chlamydia and syphilis. Their life expectancy is six years less than that of other Americans, and they are six times as likely to develop alcohol and drug dependence. “You can’t just say it is his or her problem,” says Kirk. “It’s a community problem. But there is a lot of shame.”

Over the past year, however, awareness efforts in Native American communities have become more pronounced. Embracing Our Traditions, one of the few national conferences to tackle HIV in Native populations, was launched in Anchorage in 2006. What’s more, March 20, 2008, marks National Native HIV Awareness Day, with events from parades to conferences occurring around the country. “I do believe we have made slow, steady progress,” says Wilson. “But the credit goes not to the health system, but to community leaders and advocates out there telling stories and providing a community voice.”

As one of those voices, Montoya is less optimistic: “Nothing gets done,” he says of developing concrete programs and funding. “People come and they want our input from all these committees I sit on. But nothing gets done.”

Soon after arriving in Albuquerque, Montoya developed PCP and visited an IHS clinic to get care. “I could hear the nurse talking to the doctor and saying she didn’t want to wait on me because I had HIV,” he says. Many Native Americans avoid visiting their local clinics because the employees are friends and neighbors who they fear will breach their confidentiality. And their clinics typically lack the funds and knowledge to treat HIV. “We can provide quality care if we have the right partnerships with AIDS service organizations, Ryan White [funds], and Medicaid and Medicare,” says Wilson. “If we are left with the resources we have, well, that can be a barrier.” While such referrals often work in more urban areas—where efforts like the Two Spirit movement are also working to develop a gay Native culture and combat homophobia—many native people live on isolated rural reservations, where the nearest hospital is an hour or two away. “They may have trouble getting transportation and miss their appointment,” says Kirk.

Wilson believes that reaching Natives requires tailoring programs to fit their unique culture, including educating elders and incorporating tribal health techniques. Their biannual Albuquerque Circle of Harmony Conference on HIV, organized by Kirk and facilitated by Montoya, always opens with a traditional sweat lodge and a talking circle. The next one is scheduled for 2009. “People are encouraged to share their experiences about abusing drugs or living with HIV,” says Kirk. “It’s different from most conferences because it comes from the heart, not the head.”

Kirk says that more positive Native Americans must start talking publicly to increase visibility and to get more HIV funds on track to benefit Native people. “Kory is [only] one person,” says Kirk. Montoya, who is on disability and does most of his activism on a volunteer basis, says, “It is difficult to get people with HIV who are Native to the table. They are afraid of the stigma and rejection.” Montoya says of his strained relationship with his own family, “They know where to find me,” adding, “It made me stronger. After my mother closed the door on me, I didn’t care if anyone knew who I was or knew my name.” More and more people are starting to.

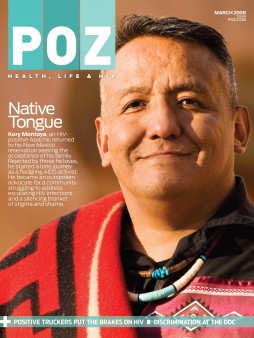

Native Soul

Kory Montoya, a New Mexico Apache, was diagnosed with HIV in 1991. Here he marks National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, March 20, by telling his story of growing up gay on a reservation and entering the army—only to return to his community to speak openly about AIDS and homophobia.

16 Comments

16 Comments