Weeks before Darrel Ellis was born in 1958, his father, a Black portrait photographer in the Bronx, was beaten to death by police. His father’s absence and artwork would profoundly influence Ellis, who grew up to become a mixed-media painter and photographer.

Ellis died of AIDS-related illness in 1992 at age 33, but the openly gay artist and his work were already being recognized—Ellis was photographed by Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe, and he died just months before an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York that included his work. Luckily, his friend Allen Frame, a writer and photographer, archived Ellis’s art, notebooks and other personal items, and he and Ellis’s family helped preserve his legacy.

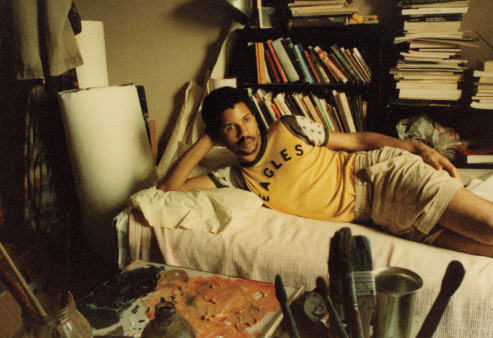

For a time, Ellis worked as a security guard at MoMA, a job that he ultimately found demeaning but afforded him the chance to study contemporary works; during his later career, he lived in a studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

In recent years, Ellis’s artwork—mostly reworkings of portraits his father made of his own family in the 1940s and ’50s—have gained popularity. Last spring, he was the subject of solo shows at Candice Madey, a gallery in New York City, as well as at a gallery in Switzerland. And now we have the publication of Darrel Ellis, a monograph by Visual AIDS, an organization that uses art to raise HIV awareness and preserves the work of HIV-positive artists (scroll through the nonprofit’s amazing digital collection, including over 100 works by Ellis, at VisualAIDS.org).

Cover of the Darrel Ellis monographCourtesy of Visual AIDS

In addition to featuring a rich variety of Ellis’s work, the book includes essays by Derek Conrad Murray, Steven G. Fullwood and Tiana Reid; a 1991 interview with Ellis by David Hirsh; and a 2000 discussion of Ellis’s work moderated by Ariel Goldberg with Black artists Sadie Barnette, Alanna Fields, S*an D. Henry-Smith and Paul Mpagi Sepuya.

Ellis worked primarily in photography, pencil, ink, watercolor and gouache (a thicker, more opaque type of watercolor). The foundation of his work is a vast collection of negatives from his father’s photography as well as from portraits of Ellis (often self-portraits). Careful never to alter the negatives, Ellis transformed and deconstructed the photos. He projected images on varying surfaces, repeated elements, blocked out faces and painted over details, mostly in grays and browns. He described his work as ephemeral and light, cerebral but soulful.

Ellis didn’t address issues like AIDS, racism and queerness directly in his work, gallery director Candice Madey told POZ last spring. “However, in his journal, he was thinking deeply about them. He questioned the Eurocentric history of art that was handed down to him and explored how to exert a Black identity that was true to himself. He presented us with beautiful, personal, intimate moments of a family—something that everyone can understand and relate to.”

“These images, like memories themselves, are warped, distorted, and obscured by the artist, as if to say, ‘You can look, but you cannot know,’’ writes Derek Conrad Murray, a Black art historian and theorist, in the Visual AIDS book. “This struggle between transparency and opacity is at the heart of Darrel Ellis’s work.”

Comments

Comments