HIV plays a prominent role in Somebody to Love: The Life, Death and Legacy of Freddie Mercury, a new biography of the rock icon and Queen front man. How prominent? The first chapter doesn’t start with the childhood of Mercury—who was born Farrokh Bulsara—but instead takes place in 1908 in Africa, when a simian version of HIV jumps to humans, kicking off the global AIDS epidemic. Fans of Queen and Mercury will have plenty to love in this rock biography, penned by Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne and chock-full of details about their hits—“Bohemian Rhapsody,” “Another One Bites the Dust,” “We Are the Champions,” the band’s show-stealing Live Aid performance in 1985 and much, much more. Mercury had sexual and romantic relationships with both women and men, and the book offers a fascinating glimpse at Mercury’s secret gay life, such as his nights at the Mineshaft, a legendary gay club in New York.

POZ emailed Langhorne to talk further about the book’s HIV angle. In fact, Somebody to Love is released this week to coincide with the 25th anniversary of Mercury’s death from AIDS-related illness on November 24, 1991, at age 45. Mercury would have been 70 this year, and the man continues to rock us.

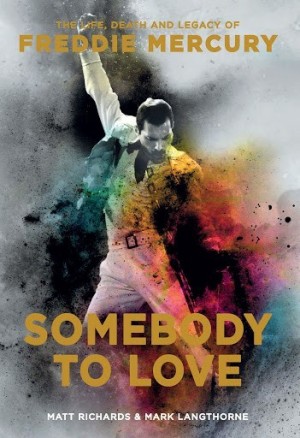

Weldon Owen

Your book reads almost like two parallel bios—one of Freddie and another of the HIV epidemic. Why structure the book this way?

Being a fan of Freddie Mercury, and a gay man who lived through the ’70s and ’80s, it seemed an opportunity to take both subjects and combine them in a unique way. There was also the challenge that we wanted Queen fans to pick the book up and learn something about the times, the individual and his personal struggle. If the book were an HIV/AIDS book, it would never gain access to the mainstream audience.

Freddie Mercury has been the subject of other bios and documentaries. What does your book bring to the discussion?

We focus on the journey not only of Freddie but also of the disease itself from its origins and follow a strand across the 20th century to when he himself was infected. All other biographies deal principally with the artist, Freddie, but we try to look deeper than that. It needed to be a story about much more than Freddie, one that many people can relate to.

You make the claim that in death Freddie has done more to battle HIV and the related stigma than he did in life. Can you elaborate?

In truth he has. It was important, and Jim Beach his manager realized this, that Freddie tell the world he had AIDS, though it was only a short time before his death. It made the disease real for many ordinary people whose lives he had touched through the music and performance—people who would never have known a person with AIDS. Therefore, it becomes something tangible, that they too had lost something and felt it.

(continued below)

Freddie Mercury backstage during the video shoot for the Queen single “Breakthru,” at Nene Valley, U.K., 1989©Richard Young

My impression from reading the book was that Freddie was rather private in general. He never publicly acknowledged he had sex with other men, and in terms of HIV, he didn’t even tell the band members or many of his closest friends until it was impossible not to. He did release a press statement saying he had AIDS, but he died the next day, November 24, 1991. Today, some folks consider that silence to be cowardly. How would you respond to such accusations?

In the book, we try to understand how Freddie became who he was, his background and upbringing, the times, the homophobia, the vile British press [that tried to out him as gay and living with HIV], the members of Queen and the pressures not just on him but for all those people around him who relied on the industry that Queen had become. It was never a case of Freddie coming out as gay and telling the world he was HIV positive and then getting on with his life. It was never going to happen. The times he lived through were corrosive and bitter.

We judge the past from a different present. Maybe we judge ourselves at the same time: what if, if only and maybe.

You pinpoint a moment when Freddie was likely exhibiting signs of acute HIV infection, which refers to the few months directly after contracting the virus. It was Queen’s 1982 performance on “Saturday Night Live,” singing “Under Pressure” and “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” He had flu-like symptoms, etc. It’s fascinating sleuth work, but I wonder, what is your purpose in figuring that out?

The purpose of discovering that was an odd realization—that he would have been HIV positive for almost a decade, which was half of his life as a star. It helps us understand why he did what he did and made creative and personal decisions and how he viewed the world postinfection. It also gives us insight into the times, and I suppose a clearer snapshot of his life. He claimed he was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 1987, but when you later learn that in fact he was likely infected five years earlier, you see a different person than the one you thought you saw. You see a person fighting.

(continued below)

Freddie Mercury backstage in Barcelona, 1988©Richard Young

Let’s talk about Gaëtan Dugas a.k.a. Patient Zero. He plays an unexpected recurring role in this book. The two met a few times and shared a common lover, plus many other parallel experiences in life and death. I admit that at first I worried where you were going with the Dugas storyline because it treaded on the fear and stigma surrounding the initial reports about Patient Zero. But then of course, you set the record straight. What were you trying to say by including so much about Dugas?

Gaëtan was a fascinating person. Characterized by Randy Shilts [author of 1987’s And the Band Played On, a pivotal book on AIDS] as promiscuous and irresponsible, he was widely vilified. In fact, you might say Gaëtan Dugas is one of the most demonized patients in history. When we began writing this book 18 months ago, I felt he was an important character in the narrative I wanted to tell, in the strand of this story about AIDS, and we always believed of course he was not Patient Zero. How could he be? Because after all, someone gave it to him. He was simply one of thousands infected before HIV/AIDS was recognized.

Very recently, he has been exonerated, and that tied in with what we first wrote over a year and a half ago. It was just common sense. No one should be blamed for the spread of a virus that no one even knew about.

At times, I read this section almost as if Freddie himself were a patient zero, with his countless sex partners and his refusal to slow down even once AIDS hit the scene. When asked whether he altered his behavior, Freddie responds, “Darling, fuck it, I’m doing everything with everybody.” What are we to make of this?

Each of us makes our personal choices. What do you want to make of it? So many of us dealt with [the AIDS crisis] in different ways—after all, there was no template then. There was no right or wrong in this. It cannot be a moral judgment. Now we can make fully informed choices [about HIV risks], but that was not the case then. We clung on to how far we had come by the early ’80s socially, politically, sexually; and then suddenly, this thing called AIDS threatened to take it all away, and then it did.

What aspect of Freddie Mercury’s life or personality surprised you as you researched this book?

The difference between the performer and the showman, and the individual and the star. Offstage he seemed somehow diminished. When I met him, I found a shy, self-conscious, awkward man, who required drink and drugs to open up. There was a sadness to him, a kind of defense mechanism, the sort that keeps even the richest man poor.

I had never heard of the theory that “Bohemian Rhapsody” was basically Freddie’s coming out—specifically, about Freddie’s leaving his female lover Mary Austin for men. Can you give us some context on that idea? Has it been well known for a long time?

During his lifetime, Freddie never revealed what “Bohemian Rhapsody” was about. “I think people should just listen to it, think about it and then decide for themselves what it means to them,” he would later say. The other members of Queen who have spoken on the subject have refused to be drawn on the matter. But for decades, people have been speculating about the hidden meaning of the song. While many took it at face value, thinking it was simply about a murderer confessing to his crime, other analysts of the song point to it being an illustration of his emotional mindset during that period. At the time of writing the song, he was already embroiled in an affair with David Minns despite living with Mary Austin. Queen’s manager at the time was John Reid, and in an exclusive interview for the book, he describes his thoughts on the subtext of “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Reid says, “There’s been so much analysis of the song, but I subscribe to the theory—and I never discussed it with him [Freddie]—that it was his coming out song.” Others agree: Lyricist Sir Tim Rice says, “I heard the record very early on, and it struck me that there is a very clear message contained in it. This is Freddie saying, ‘I’m coming out. I’m admitting that I’m gay.’”

In writing this book, we were able to dig deeper into this masterpiece and explore these claims. In doing so, our detailed analysis of the lyrics point to Mercury’s inner turmoil. Even the word bohemian is defined as a socially unconventional person, and it’s possible to create a homosexual subtext to virtually any phrase from the song. For example, “Mama, just killed a man” is not necessarily about the criminal act of murdering someone but more the metaphorical act of killing his old self, the heterosexual man. The phrase to “spare him his life from this monstrosity” is possibly a plea to the Almighty, pointing to a life in denial [of being gay], while the final line of the song suggests a place of acceptance with “any way the wind blows.” Freddie considered “Bohemian Rhapsody” to be his greatest accomplishment. Whether or not it was an autobiographical testimony to his homosexuality, the tragic narrative of the song’s text would take on an even greater meaning after his death.

Talks of a Queen biopic once again are making headlines, this time with “Mr. Robot” star Rami Malek as Freddie. What are your thoughts on this and the role that gay sexuality and HIV should play in the film?

There has been a great deal of conjecture about the movie. I was told that the movie focuses only on his life as a performer and that post–Freddie’s death [which happens midway in the film], the movie continues with the Queen story without him. I understand it will not be dealing in depth with Freddie’s sexuality or his death, which seems to me to be missing the point. After all, he was one of the most famous casualties of AIDS, and his death and life are inextricably linked.

Finally, what are your personal connections and interest in Freddie Mercury and the HIV epidemic? What drew you to write this book?

Personal loss—and the belief that the life and the times should be documented. And Freddie was such an interesting individual, who represents so much of what was part of the thing we had and then lost. So many people full of life who died, and I miss still. I think of this book as a personal memory box, too, and I hope people take something away from it.

Somebody to Love is available now. Below, we’ll leave you with a clip of Queen’s iconic mini-concert at the Live Aid fundraiser in 1985.

24 Comments

24 Comments