A golden afternoon in lower Manhattan is seen a few stories above the street. A thin white woman clings for her life to the side of a skyscraper. A light breeze catches her hair. Traffic moves below. There is no one or nothing to catch her if she falls.

This image, played on loop, is seen by visitors of “AIDS: Based on a True Story,” an exhibition curated by Vladimir Čajkovac for the German Hygiene Museum. I was in residence at the museum for the exhibition, which closed last month in Dresden; it will be remounted elsewhere in Europe later next year.

“AIDS: Based on a True Story” is an overall view of the ongoing global pandemic via contemporary art, AIDS posters and historical artifacts. At a cultural moment rich with exploration of early responses to HIV/AIDS, the exhibition upends expectations—and challenges both viewers and institutions to question what an art exhibition can and should do.

“The Horizon,” the video scene describe above, was created by artist Maja Cule. She did not make it with HIV/AIDS in mind. Rather, she was inspired by a classic film trope: a woman in peril.

But of course, context is everything.

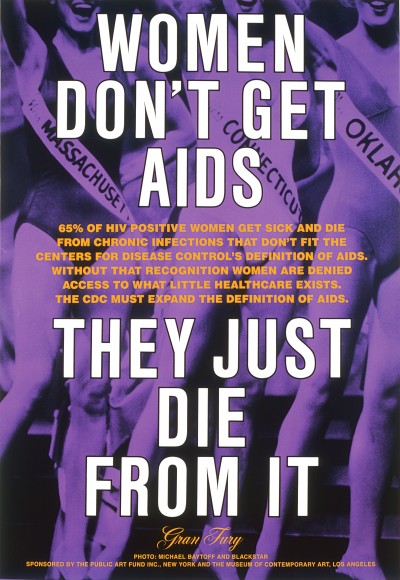

Looking up from the video, the viewer’s field of vision is directed upon the canonical “Silence = Death” image created in 1986 by the political collective of the same name. The Gran Fury poster, “Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die from It,” (1991) hung in the next room. This triangulation of art, iconography and urgent messaging exemplified the framework of the exhibition: a commitment to holding the tension of the social, physical and scientific aspects of the ongoing crisis. Čajkovac not only addressed the Hygiene Museum’s mission to present exhibitions on “cultural, social and scientific revolutions taking place in our society,” he created an experience that mirrors the often complex, interconnecting stories and strategies that make up the ongoing AIDS crisis and our various responses.

Women Don’t Get AIDS, They Just Die From It, 1990Gran Fury

The Cule video and two AIDS posters provided an entryway to a myriad of questions and conversations about the epidemic. What is the role of images, symbols and text that are deployed within AIDS activism? How do we reckon with the premature deaths of many HIV-positive women early in the crisis because the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s narrow definition of AIDS meant women were unable to get the care and support they needed? (This is the original impetus of the Gran Fury poster.) In what ways have women impacted the HIV crisis, including as activists who ensured there was a safety net to catch those living with HIV? From these questions, an argument can emerge: the silence around HIV and women is historic and ongoing. It impacts the survival of women living with HIV, and it too easily dismisses the contribution of women in the ongoing response. And this is just one conversation amid many that are formed within “AIDS: Based on a True Story.”

The exhibition was made up of five rooms, each designated by an idea: The Illness of Others, Breaking Silence (in which the video and the posters appear), AIDS As A Media Event, The Virus, and Living Together. In addition, the museum’s theater screened 40 recent AIDS-related public service announcements from 20 different countries, including United Arab Emirates, Germany and South Africa. The exhibition also included a gallery in which 140 of the museum’s collection of 10,000 AIDS posters from around the world were arranged by key words such as: war, medicines, syringe, sexuality and contact.

Čajkovac’s fascination with classification and key words is a cornerstone of his larger commentary. Science and media—not as disparate as one may think—come together to create, circulate and maintain narratives about illness, wellness and behavior. Čajkovac quotes theorist Paula A. Treichler in the catalog, “AIDS is not merely an invented label, provided to us by science and scientific naming practices…rather, the very nature of AIDS is constructed though language.”

This method of sorting and understanding the virus moved beyond the structure of the exhibition and was exemplified by several works that played with the idea of categorizing a virus. One example was a selection of clothes by designer Silvio Vujičić, which were created by a weaving loom he had infected with a computer virus, resulting in modifications in each garment. Another was “Forkbomb” by Denis Roio aka Jaromil. Forkbomb is a line of computer code that if entered into a Unix system computer would cause it crash. The code commands the computer to make multiple copies of it, which overwhelms the computer’s resources (like HIV overwhelms our body’s immune system). Both of these works served as a provocation, begging the question that scientists (and Čajkovac) wrestle with: Is a virus a living thing or a packet of circulating information?

The exhibition also used many popular AIDS narratives to illustrate the ways in which we have incorporated them into our lived experience, and to provide the space to not only understand the function of these narratives but also to then question them.

Throughout “AIDS Based on a true Story,” a spectrum of the ‘AIDS Famous’—a term to denote the specific fame that comes from being associated with HIV—popped up in surprising places. In the AIDS as Media Event room, a video of Elton John singing at Ryan White’s funeral played just out of earshot of a poster of activist Linda Carole Jordan and her children. (Jordan was one of the first African-American women to appear on AIDS prevention posters.) Screening in between Elton and Linda was the MTV movie about “Real World” star Pedro Zamora.

Upon leaving the Media Event room, visitors encountered a large print from Christa Naher’s photo collage series “Engelordnungen,” in which she cut out the familial faces in her personal photographs and replaced them with images of Freddie Mercury. The title of the series means “angel arrangements” and the artworks were Naher’s way of dealing with HIV in the family.

Installation of the ’AIDS Worldwide’ roomCourtesy of the Deutsches Hygiene Museum Dresden

In many ways, the AIDS Famous become specters through which we can project, promote and sublimate. It can be easier to deal with celebrities who are living with HIV and dying from AIDS-related causes and raising awareness for the epidemic, than the idea of HIV in our own bodies or in the bodies of those we know intimately. In her infamous essay, “The Uses of the Erotic,” Audre Lorde uses pornography to illustrate what the erotic is not: “pornography is a direct denial of the power of the erotic, for it represents the suppression of true feeling. Pornography emphasizes sensation without feeling.” In other words, pornography is flat, compared to the unknowable chaotic depth of the erotic. And when dealing HIV and the tumult of the lived experience, rendering the world flat is a way to deal and to avoid any feelings about HIV until there is enough support to dive in.

In our culture one experience of HIV that is frequently rendered flat—read: pornographic—is the ubiquitous AIDS poster, a 2D surface often created by committee. The AIDS poster is tasked with the nearly impossible: sharing clear, rational and non-offensive information about a death-causing virus transmitted by sex, drugs and birth. The flatness of the delivery makes nuance and context almost impossible. When it comes to HIV, to borrow from media theorist Marshall McLuhan, the medium of the AIDS poster should not be the message. And yet, it is, and remains, a largely unexamined staple within the AIDS media landscape.

Before he curated “AIDS: Based on a True Story,” Čajkovac worked at the Hygiene Museum as a research fellow where he embarked on “an intercultural comparison of posters and their imagery,” a project sponsored by the German Federal Cultural Institution. In Čajkovac’s hands the AIDS posters went from what scholar Lawrence Lessing would call “Read Only” media files, to “Read/Write” media files: interactive and instructional cultural objects that communicate beyond their obvious content.

Čajkovac explored the genesis of many of the museum’s 10,000 posters—with scientific assistance from Kristina Kramer-Tunçludemir—to find the people involved in creating the work: photographers, illustrators, models and organizers. In the process, many of the posters came alive through personal anecdotes, gossip, cultural context, and sometimes even further mystery about its origin. Čajkovac writes, “The project began at the point of transition where AIDS posters went from being instruments of health education to museum artifacts, thus transforming the AIDS epidemic into a narrative.”

Extending this idea is the heart of the exhibition, the third room, entitled The Virus. It contains more than a dozen posters from around the world in which HIV is depicted in a variety of ways: as bomb, monster, snake, ocean critter, and yes even as a virus. The creativity is credited to artists, graphic designers, community members and scientists. As the wall text points out, even the medical community gets creative, coloring microscopic views of HIV to make it more visible. Science is not immune to needing narrative to make an argument.

Installation of ’The Virus’ room, which included a collection of work by Zephania Tshuma, 1988-1992Courtesy of the Deutsches Hygiene Museum Dresden

To animate the lived experience of HIV, Čajkovac curated a series of sculptures from the Hygiene Museum’s collection of work from former Red Cross District Manager, politician and artist, Zephania Tshuma (1932–2000). With names such as “Checking for AIDS,” and “AIDS Worm,” Tshuma’s sculptures work in an almost inverse fashion to Cule’s video of the lone woman on the building. While her video becomes infused with HIV due to proximity, Tshuma’s work—made with HIV in mind—delivers an awareness of the factors that surround a community living with HIV: relationships among sexual partners, fear, condoms, folklore and witness. Displayed on a multilayered platform, the works become an uncanny reproduction of visitors in the gallery, surrounded by the virus, looking, wondering and indulging in an AIDS related quest for meaning.

First and foremost, HIV is a virus that according to the World Health Organization lives in 36.9 million people world wide, and according to amfAR, is related to the AIDS-related deaths of over 39 million people since we started keeping track. Outside the body the presence of HIV has political, social, spiritual, physical and cultural implications. To make sense of the virus and its ramifications one needs to embrace its assemblage realities, the accumulation of meanings, scientific knowledge, personal experience and everything else. Employing Treichler again, Čajkovac reminds us in the catalog that AIDS —among all of its definitions— is also, “an epidemic of meanings.”

In “Tangled Memories,” theorist Marita Sturken writes about how scenes from films about historical moments come to replace memories of those who lived through the actual experiences being represented. As more time passes between the earliest days of AIDS and the present, the harder it will be to have a discussion about HIV rooted in the stories of long-term survivors and witnesses as the primary resource. “AIDS: Based on a True Story” does not try to stop the movement of time, or the flow of media creation. Rather it works to question how we receive information about the epidemic, giving us speed-bumps along the way to consider what we are taking in, and what we want to do with that information.

Media literacy is one tool those involved in the ongoing response to HIV need to keep sharpening. In “AIDS: Based on a True Story,” Čajkovac helped challenge what we think we know, and gave us the space to consider how narratives around HIV/AIDS are formed and the function they provide in circulation. By questioning knowledge we open up the possibility to learn more, and rid ourselves of unhelpful or outdated information, better enabling a possibility for us to work together to produce narratives for a better future.

AIDS, like life, is based on a true story that we create collectively.

Theodore (ted) Kerr

Theodore (ted) Kerr is a Canadian-born, Brooklyn-based writer and organizer whose work focuses on HIV/AIDS. He was in residence at the German Hygiene Museum for the AIDS: Based on a True Story exhibition. Kerr was the programs manager at Visual AIDS and is currently at Union Theological Seminary researching Christian Ethics and HIV/AIDS.

Comments

Comments