The idea was born in a Washington, DC, jail cell. Charles King, who heads up Housing Works, an AIDS service organization in New York City, was locked up for several hours alongside Treatment Action Group executive director Mark Harrington. The two veteran activists had committed their latest act of civil disobedience, this one before the White House during the International AIDS Conference in July 2012. Killing time, they found themselves lamenting what they saw as the ineffectual nature of the Obama administration’s National AIDS Strategy, which, King believes, “is a strategy to maintain the epidemic, not to end it.”

But what if they could find a way to end the epidemic, at least as a test case on a smaller scale? New York seemed primed for such a possibility. Not only were key epidemiological trends in the state moving in the right direction, but a pending redesign of its Medicaid program would also eventually free up funds that could be spent in new and creative ways. What’s more, the full implementation of the Affordable Care Act stood to open new avenues for the fight against HIV.

Flash forward to June 2014: Governor Andrew Cuomo announced his administration’s audacious “plan to end the AIDS epidemic in New York.” The idea is to “bend the curve” and reduce the number of people living with the virus in the Empire State for the first time through three main efforts: improved HIV diagnosis and linkage into care, improved retention for those in care along with expanded antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and a push to get high-risk New Yorkers on Truvada (tenofovir/emtricitabine) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

King’s leadership had succeeded in bringing numerous parties to the table, including LBGT groups, AIDS service organizations, pharmaceutical companies, the public health sector and of course the state government. By getting on the end-of-AIDS bandwagon, these groups fell in lockstep with forces working on an even grander scale toward that ambitious goal. This includes the Obama administration, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria. In recent years, all of these entities have pledged to strive for a not-too-distant end to the epidemic and have committed to the goal with a fervor and optimism not seen since the introduction of combination HIV therapy in the mid-1990s.

This is enthusiasm that some eye warily, if not with outright hostility. Skeptics worry that such lofty promises will fall flat, leaving once-excited donors and other stakeholders disillusioned to the point of closing their pocketbooks and turning their eyes to other concerns.

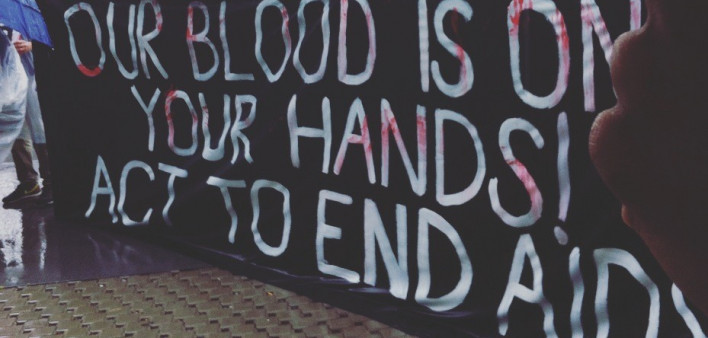

In a screed he blasted to various email listservs on the eve of July’s International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, ACT UP alumnus Gregg Gonsalves lambasted end-of-AIDS rhetoric as “a strange strain of utopianism” and “a mirage leading us astray” from the all-too-real difficulties of dealing with the global AIDS crisis in the present.

Wafaa M. El-Sadr, MD, MPH, director of the global health organization ICAP at Columbia University, led a three-person group that published an editorial in the journal Science on July 11 titled “End of AIDS: Hype Versus Hope.” The piece argues that campaigns promising “imminent success” in the battle against AIDS “may be perceived as minimizing the challenges that remain, resulting in the withdrawal of resources and a consequent resurgence of the presumed ‘controlled’ disease.”

Old tools, a new finding, renewed hope

Campaigns to end the epidemic were on the upswing in the late aughts. The movement received a major scientific boost in May 2011, when the findings of the famed HPTN 052 trial were announced. To the great excitement of the international AIDS community, the study showed that ARVs cut the risk of transmission in mixed-HIV-status heterosexual couples by 96 percent. Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, wrote an editorial in Science that ran in July of that year in which he enthused, “We finally have scientifically validated prevention modalities that clearly work, suggesting that ending the pandemic is feasible.” Treatment as prevention, or TasP, had become a beacon of hope.

By November 2011, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton gave a speech announcing a new push for an “AIDS-free generation,” which has remained the cornerstone of the Obama administration’s global AIDS strategy. The fuel behind this effort are three of Fauci’s “prevention modalities,” each of which has been scientifically proved to reduce the risk of HIV transmission: expanded HIV treatment, voluntary medical male circumcision (which cuts female-to-male HIV transmission risk by 60 percent), and the treatment of HIV-positive mothers to prevent mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of the virus. In addition, there are the age-old strategies of HIV testing and counseling and condom distribution.

On December 1, 2011, World AIDS Day, both President Barack Obama and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon also made specific calls for an end to AIDS.

The lingo trickled down. Adopting such language in their public relations strategies were groups such as amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research, which frequently speaks of an eventual end to AIDS in its fundraising pitches. Then there’s Whitman-Walker Health, the Washington, DC, AIDS service organization that recently changed the name of its AIDS Walk to “The Walk to End HIV.” The event’s ad campaign is called “The Finish Line.”

UNAIDS has since called more specifically for “ending the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat” by 2030, a goal shared and supported by the Global Fund.

All of which raises the question: What exactly is the “end of AIDS”?

“At one extreme there would be no more people with HIV in the world, and at the other extreme there would be no more people with advanced HIV disease, meaning AIDS,” says El-Sadr. “In between those two extremes there is everything in the middle.”

Tailoring the message

Ultimately, slogans are about salesmanship, whether they’re reminding us that Coke Is It or that Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires. When it comes to end-of-AIDS pitches, the slogan, however nebulous or elusive its actual meaning, is typically intended to prime the interest of those writing the checks or opening the necessary political doors (or not shutting them, as the case may be). Then, of course, there is the behavior of the general public, which, when swayed by effective messaging, can help end the epidemic (or perhaps favor a politician they perceive, accurately or not, as being proactive). This pitch also takes into account what tools the group spouting the slogan either has or can hope to have at its disposal. Consequently, each definition of “the end of AIDS” is bound by the respective entity’s particular approach to achieving that goal.

According to Kevin Frost, CEO of amfAR, reaching the end of AIDS will take “a very, very long journey, and it requires tools that frankly we don’t have yet. It requires a vaccine, it requires a cure, and it requires many things that simply don’t exist.”

Such a position dovetails with the fact that a central focus of amfAR’s efforts is the search for a cure to HIV. The nonprofit’s fundraising messaging suggests that supporting this research will lead to an end to AIDS. The strategy has paid off: While other AIDS groups around the country have seen their funding dwindle, amfAR’s has doubled during Frost’s seven-year tenure, which he attributes to how successfully such aspirational messaging resonates with amfAR supporters.

As for the definition of an end to AIDS, Frost says, “I believe the goal should be to completely eradicate this disease. And just as with smallpox, I believe it can be done.”

Meanwhile, UNAIDS, the Global Fund, and the Cuomo administration in New York are each clear in their position that we do have the tools necessary to end AIDS as an epidemic, and that such an end would see many people living long and healthy lives with HIV.

The various stakeholders helping shape the particulars of the New York state plan have two benchmarks that they hope to reach in the near future and that they say will help herald an end to the state’s AIDS epidemic.

The first goal is to reduce by 75 percent the number of new HIV infections in the state, from 3,000 in 2012 to 750 in 2020. Considering there are approximately 150,000 people in New York State living with HIV, this effort would cut the annual “transmission rate” from 2 percent to 0.5 percent and likely cause the state’s epidemic to shrink. The state plan’s other benchmark is to reduce the proportion of New Yorkers who test positive for HIV and who then receive an AIDS diagnosis within two years from 10 percent to 5 percent, also by 2020.

More goals and greater clarity on the precise meaning of an end to AIDS in New York are to emerge as details are hammered out in preparation for the governor’s budget proposal in January.

The UNAIDS plan is geared around a pair of goals for the global HIV epidemic. The first is to have 90 percent of people living with the virus know their serostatus, 90 percent of that group on ARVs and 90 percent of that group achieve an undetectable viral load—all by 2020. (Which means that 72 percent of the global HIV population would have a fully suppressed virus.) This, according to mathematical modeling, should put the world on target to achieve, by 2030, a 90 percent reduction in new infections—to 200,000 per year—and a 80 percent reduction in AIDS-related deaths, compared with 2010 figures. While Gonsalves in particular finds fault with the lack of more specific benchmarks in the UNAIDS plan, there are indeed others in the works.

Frost is critical of the UNAIDS concept of the end of AIDS, saying, “If you took the UNAIDS definition and substituted the word ‘polio’ for ‘AIDS’ you could argue that we have ended polio. And by that definition you might be right, since ‘ending an epidemic’ and ‘eradicating a disease’ are different. But with HIV, the UNAIDS definition would reflect my [position] that a definition that leaves millions living with HIV but just not dying from the disease does not reflect what a person on the street might interpret ‘ending AIDS’ to mean.”

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain

But can all these lofty goals actually be achieved, and in the promised time frame? Take the Obama administration’s AIDS-free generation goal. In Hillary Clinton’s words, the expression means that “virtually no children are born with the virus. As these children become teenagers and adults, they are at far lower risk of becoming infected than they would be today thanks to a wide range of prevention tools. And if they do acquire HIV, they have access to treatment that helps prevent them from developing AIDS and passing the virus on to others.”

Four years after the plan was announced, that vision is already proving elusive. One of the administration’s initial goals was to reach zero mother-to-child transmissions globally by 2015. But while 2001 to 2013 saw a 60 percent drop in annual MTCT incidence, from about 500,000 to 200,000, the trend puts the figure a far cry from reaching zero by next year. Furthermore, U.S. investment in battling the global epidemic has largely stagnated since 2011. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief’s budget, which includes contributions to the Global Fund, stood at $6.725 billion four years ago and is an estimated $6.756 billion today. The proposed 2015 budget is $6.403 billion.

The Obama administration is also guilty of flat-out lapses of logic when making promises about AIDS’s demise. During a 2013 World AIDS Day speech, Secretary of State John Kerry proclaimed that an AIDS-free generation was “within sight.” But according to the very definitions laid out by his predecessor, the AIDS-free generation won’t even be born until MTCT is virtually eliminated, and for good; and two more decades will need to pass for those children to grow up and make it past all the other benchmarks.

“You must have really good vision to see” the AIDS-free generation, quips Mitchell Warren, AVAC’s executive director.

Referring to the UNAIDS HIV treatment goals for 2020, Warren says, “I’m all for being bold and audacious, but to be beyond aspirational, to say that we’re at 72 percent viral suppression globally in less than a decade is, I think, not a realistic target. I want something that is feasible but ambitious.”

By comparison, only 28 percent of Americans living with HIV have complete viral suppression. In El-Sadr’s Science editorial, she and her coauthors point out that, in low- and middle-income countries, just 34 percent of women and 17 percent of men with HIV have access to treatment.

Warren worries about accountability for these promises. “As I said to [UNAIDS executive director] Michel Sidibé and others [at the International AIDS Conference] in Melbourne, ‘None of you are going to be around in 2030 in your jobs,’” he recalls. “‘That’s 16 years from now. Who do I hold accountable when you don’t reach the target?’”

Put on a happy face

According to Kent Buse, PhD, senior advisor to the executive director and chief of strategic policy directions at UNAIDS, the organization’s decision to adopt such a lofty end-AIDS campaign strategy occurred in the context of countervailing forces that sought to stop disease-specific UN programs and funding. Additionally, given the economically austere environment, critics said UNAIDS should be folded into the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, the public’s interest in HIV has of course waned, with fewer seeing the disease as a pressing issue. So, in an ironic turn, convincing the world that AIDS isn’t over has required speaking of how it could be over, thus reminding everyday people of the ever-present threat.

“AIDS needs to struggle to retain and maintain some visibility,” Buse says. “And even in the health sector we see AIDS to some extent being pushed off by non-communicable diseases and universal health coverage. And that’s not to say that we think this is a zero-sum game.

“We think if we don’t deploy this sort of language that we will be ignored,” he says of end-of-AIDS slogans. “I think the AIDS response has been quite unprecedented in the way that it has approached issues and it’s been quite unprecedented in terms of the progress that it’s achieved. And we need to be telling that story so we can continue to attract investment.”

Global Fund executive director Mark Dybul, MD, says that attracting investment from nations requires a finesse that is informed by epidemiological trends and mathematical modeling and is indeed buttressed by the organization’s track record in fighting the disease.

“If you’re saying, ‘AIDS is over and we can walk away,’ that’s a problem,” Dybul says. “If you’re saying we’re on the trajectory now, that we’re really at a historical tipping point where we have the ability to get to the end of the epidemic—as an epidemic, not to eliminate HIV, but to get to low-level endemnicity—that’s pretty attractive to donors. Saying we’re going to be paying for this for the next 75, 100 years and there’s no way out isn’t a very attractive thing for resource mobilization.”

As for what “low-level endemnicity” means where HIV is concerned, Dybul says the global scientific community is still ironing out those details.

And concerning the tipping point, Dybul and Buse point to modeling that says an immediate accelerated attack on the disease can drive trends downward. Wait even a few years to scale up efforts, and the amount of time, money and effort required to achieve the same result will be much greater.

Meanwhile, the New York faction is feeling especially confident that end-of-AIDS messaging will resonate with people and that the effort will ultimately prove successful.

“I think that this conversation [about ending AIDS] actually energizes people,” says Dan O’Connell, director of the AIDS Institute at the New York State Department of Health. “If you do it in a certain context where it’s a pie in the sky and not realistic, you’re definitely going to get some pushback and people worried that you are trying to oversell something. But I think where we are in New York it is perfectly feasible to do what we say we’re going to do.”

“I do see this as a defining moment,” says Housing Works’ Charles King, “and I feel a tremendous sense of responsibility. Because the truth of the matter is, I honestly believe that if New York State actually implements a plan that really bends the curve toward zero, that we will pave the way for other states to follow. And if we fail to do it and it’s just a slogan and everybody doesn’t get harnessed on it, we will be probably be setting back the movement in the United States at least a decade. And it will be a long time before another governor steps forward and says, ‘Oh, yes, we can.’”

4 Comments

4 Comments