In an ongoing interview series reflecting on the mission of The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, Brooklyn-based writer, playwright, and artist Rehan Ansari, along with Sara Reisman and George Bolster, from The Foundation speak with institutions and individuals whose work centers on art and social justice. In this interview, they spoke to Esther McGowan and Alex Fialho of Visual AIDS, and Sur Rodney (Sur), independent curator, writer and archivist, former board member of Visual AIDS about the activist legacy of Visual AIDS; its importance in our current moment; the challenge of HIV criminalization; the history of AIDS activism as a white male story, now being challenged; and whether this is a more difficult time to make political art and allies.

Rehan Ansari: If I Google ‘Visual AIDS’ and ‘legacy’ what would I not find that you’d like me to find?

Esther McGowan: There are some really important early projects and a legacy of the organization in terms of the beginnings of AIDS activism and art in AIDS activism you may not find. The Visual AIDS Artist Caucus created the red ribbon to represent AIDS activism and the support and caring for people living with HIV. That ribbon became so ubiquitous, that the idea of someone creating it doesn’t always come to mind. You may also not find early activist projects that we did with prominent artists like Glenn Ligon, Barbara Kruger and John Giorno experimenting with ways to use art in broadsides, which were publicly distributed for free to encourage people to learn more about health.

Red Ribbon-making workshop (1991)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

What you WOULD find about us is a lot of our recent projects and public programs—exhibitions, activist projects, artist commissions. For example, LOVE POSITIVE WOMEN is an art-making workshop envisioned by Visual AIDS Artist Member Jessica Whitbread that helps reduce stigma for HIV-positive women.

LOVE POSITIVE WOMEN workshop (2019)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

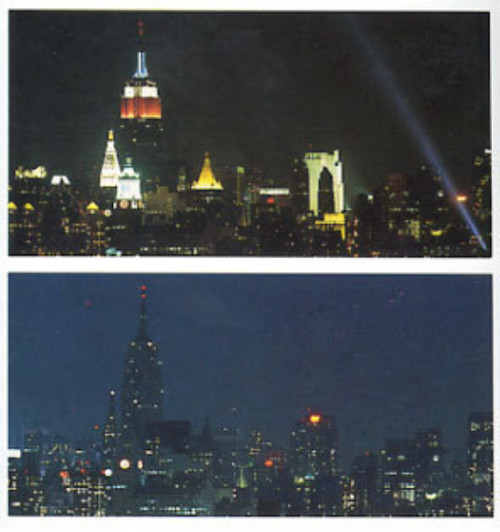

Sur Rodney (Sur): In the early stages of Visual AIDS there was a need to communicate how the epidemic was affecting the art world. On December 1, there was programming around targeting museums and galleries to cover artwork, dim lights, and curate shows that informed the public that there was something they have to acknowledge or mobilize on, for instance when people observed the Night Without Light. Now, it’s condensed itself more into programming that brings communities together inside of safe spaces rather than the broad public engagement happening all over the city simultaneously like A Day With(out) Art, A Night Without Light and Electric Blanket.

Rehan Ansari: Can you explain A Day With(out) Art, A Night Without Light?

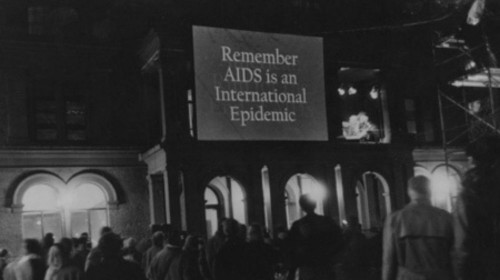

Sur Rodney (Sur): A Day With(out) Art originally started with activists asking museums to shroud artworks and dim gallery lights. Some institutions were encouraged to change the artwork in their galleries to highlight the AIDS epidemic, and some galleries turned their space over to curators to curate shows. Visual AIDS was really the organization that continually plodded along and introduced artists doing work around HIV/AIDS to a wider community.

Esther McGowan: In the early ’90’s, for A Night Without Light, they worked with real estate developers all over the city who simultaneously turned off the lights on sky-scrapers to darken the city as a symbol of loss and the AIDS crisis. The person who spearheaded that as a partner to Visual AIDS was Robert Durst the real estate developer. We found a stamp of his signature in our archives; we would send letters out from him to all the other real estate developers saying, “I’m supporting this. We hope you’ll support it.” It worked: a large number of buildings turned their lights off all at the same time.

A Night Without Light (1990)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

Rehan Ansari: And what was Electric Blanket? And then RADIANT PRESENCE, which is something you did recently.

Alex Fialho: Electric Blanket originated in 1990 by Allen Frame, Frank Franca, Nan Goldin and others. They selected hundreds of images around three themes—Memorial, Action and Document—and projected them onto the building of Cooper Union for World AIDS Day, Day With(out) Art. This idea caught on and projections occurred for more than a decade all over the world. When we approached Allen, Frank and Nan about the possibility of showing it again, they were tied to the idea of a projection via slide carousels because that is how it was done initially. That wasn’t a project that could be distributed widely, so we did a re-make as RADIANT PRESENCE and chose artworks from our Artist+ Registry to show at nearly 100 locations, including the facades of the Guggenheim, the Metropolitan Museum, the former site of Saint Vincent’s Hospital in New York, the Castro Theater and the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and more.

Electric Blanket (1990)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

Esther McGowan: For RADIANT PRESENCE in 2015 we could not get permission from the city to project onto the outside of buildings. We actually ended up doing it guerrilla-style working with an artist collective called The Illuminator who specializes in this. The New York City administration considers all images with words as advertising.

Kay Rosen’s “AIDS ON GOING GOING ON” (2013) projected on the Metropolitan Museum by The Illuminator for RADIANT PRESENCE, Day With(out) Art 2015.Courtesy of Visual AIDS/Elliot Luscombe (lvscombe.com

Sara Reisman: That idea of words in public space being advertising started during the Bloomberg Administration.

Esther McGowan: That is why the city has changed. Certain types of activism are obstructed because it’s all about pay to play. So an artist has no option but to intervene. The outdoor projections of RADIANT PRESENCE were some of the first activist interventions we had done in a while.

Alex Fialho: Regarding legacy: a major responsibility of Visual AIDS is to represent or preserve the legacies of artists who have passed from AIDS-related complications. Our website has links to artists who otherwise don’t have representation on the Internet. It feels very important that we are an organization that, when an artist passed from AIDS, people could point to as having the archive of that artist’s material. All the work, of digitizing photography, slide archiving, feels like an important thing to acknowledge in terms of preservation.

Esther McGowan: The idea came from the artist Frank Moore who was involved with Visual AIDS and wanted to create an archive to preserve images of artwork by people who were dying that would otherwise be lost. At the height of the AIDS crisis, many people were ostracized from their families and neighbors, and their art would be thrown out. Frank and David Hirsh came up with the idea of creating an archive of images. People now are living long-term with HIV, so it’s not just the legacy of people who passed away, but also of those living with HIV who continue to make work. The online Artist+ Registry is something that allows visibility for artists that don’t have representation, who make art at home from a place of personal love or the need to make art as healing.

Sur Rodney (Sur): Early on, David Hirsh was doing most of the fieldwork for the Archive Project; he was finding the work. We began photographing the work because many artists didn’t, or were diagnosed with HIV and had no time to think about what to do with the artwork. Frank and David along with Geoffrey Hendricks and myself approached the board of Visual AIDS to initiate the project as a a part of Visual AIDS.

Rehan Ansari: So how does one access it?

Esther McGowan: The Artist+ Registry is available online on our website. It’s organized alphabetically and famous artist are alongside artists you’ve never heard of. Artists have up to 100 images on their page and can be contacted. We have an ongoing web gallery project that Alex puts together—every month we bring an outside curator in to curate specifically from the registry. You can also make an appointment to come into our office and look at the slides. That was the way that it was done from 1994 until new forms of media became popular.

Rehan Ansari: What is Visual AIDS planning because of where the AIDS pandemic and crisis is currently, for example with the criminalization of HIV?

Esther McGowan: Activism is our legacy. At the height of the pandemic there was a sense of urgency so there was a lot more physical activism. Over the years we have backed away from the activation of public spaces and have produced more exhibitions, books, public programs, but we’re looking now at ways to be more activist. Recently, we marched in the Pride Parade with a contingent that was educating people about HIV criminalization. We worked to create an iconic image with Avram Finkelstein, who was a member of Gran Fury and the Silence = Death Collective. During the march we handed out a broadside that folds out to a poster, and includes information about the laws and what people can do, and resources where they can learn more. A recent exhibition, Cell Count, was also about HIV criminalization.

Visual AIDS Criminalization broadsideCourtesy of Visual AID S

Rehan Ansari: Can you talk about these laws and the activism needed to change them?

Esther McGowan: It’s important to note that Visual AIDS is not spearheading the activist work around this issue. We are influenced by The SERO Project, the Institute for HIV Law and Policy, and others who have been working at the frontlines of this issue.

Alex Fialho: One issue is that the law criminalizes non-disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners. These laws were created on a state-by-state basis, which makes them difficult to shift on a federal level. Many were conceived in the ’80’s and ’90’s, and don’t take into account current research and treatments. Actual risk of transmission has no bearing on whether or not one can be incarcerated for HIV criminalization. HIV-specific laws have led to sentences of over 30 years. People have even been incarcerated for spitting and biting despite the fact that HIV cannot be transmitted through saliva. HIV status can also be used to heighten sentences for crimes related to sex work.

We coordinated a panel during Cell Count, with Kyle Croft and Asher Mones, titled Dismantling HIV Criminalization, with Kate Boulton, a lawyer from the Center for HIV Law and Policy and Robert Suttle from the SERO Project, along with other activists spearheading the issue. Decriminalizing HIV is a nation-wide effort that Visual AIDS is now involved in. There has been some impact. Recently in California, the law was shifted to require an intent to harm to be established and it was reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Sur Rodney (Sur): The message is that if you are living with HIV, you’re a deadly weapon and if you engage in sex with anyone, whether you use a condom or have an undetectable viral load, it doesn’t matter. You are considered to be putting another person at risk. There’s no onus on the accuser to prove that they did not know. It’s also creating a problem with testing, because if someone doesn’t know their status they can have as much sex as they want, right?

Alex Fialho: It prevents prevention.

Esther McGowan: And the laws were made at a time when the understanding of HIV and AIDS and medical interventions were very different. Our work in this area is about educating people and changing the law.

Alex Fialho: Two artists included in Cell Count, Chad Clarke and Brian Carmichael, have been incarcerated. Brian made sculptures out of materials he could access during his prison sentence. Chad makes sculptures as a way to process his past experience of being incarcerated due to HIV criminalization. We invited him for an artist talk, but he lives in Canada and is technically registered as a sex offender there—because of HIV criminalization—and he couldn’t cross the border.

The curators extended the history of criminalization to the larger context of medical and state surveillance, in part by including Doreen Garner whose work looks at the insidious gynecological experiments on Black women by Dr. Marion Sims, and Dr. Muhjah Shakir who makes provocative quilts with women in Tuskegee around the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiments conducted on Black men. There is a long history of state-sanctioned medical violence against marginalized communities and Cell Count contended with these issues.

Rehan Ansari: And most of these laws are from the ’80’s? Or are they earlier than that?

Esther McGowan: The earliest is maybe from ’86. The laws started to come about at the time when states were talking about interning people living with HIV. That was something that was actually discussed and almost passed in several states. This idea of containment and punishment was something that was and remains very real.

Sur Rodney (Sur): In the early demonstrations law enforcement wore rubber gloves because of the fear of contamination. It was the same in the hospitals. Many doctors and nurses would not treat patients. There was an article in the New York Times in ’86 about how it was mandated that doctors had to go and deal with these people, but there was no oversight or control so there was a lot of fear and chaos, and people being over-medicated.

Alex Fialho: There was the Ryan White CARE Act, which was the first time federal funding was given to states for HIV services, but in order to receive funding each state had to prove it could prosecute any individual with HIV who knowingly exposed another to the virus.

Rehan Ansari: What is happening now with this administration and with the community that you serve?

Esther McGowan: There are a lot of issues happening to the trans community with the rolling back of rights. The HIV and AIDS Commission was completely disbanded and Trump couldn’t care less. One of the biggest issues is the mess this country’s health care system is in. We have always said that health care is a human right and we want to be more activist.

Sur Rodney (Sur): There’s a lot of pushback by marginalized communities of color who feel their voices have been compromised or not represented because there’s this whole re-visitation of AIDS. The history of AIDS and how it began is a story of white, gay men who owned everything. It’s rising to the surface as this question: “Why isn’t anyone talking about us?” There is also the question around women and HIV. Through researching ACT UP I’ve learned that a lot of the organizing around events were coordinated by women in the group. The infrastructure that supported ACT UP was provided by women and women’s collectives. The projects these collectives did independently were much bigger than anything that’s happened with ACT UP. The women’s collective organized a demonstration at Yankee Stadium during the World Series, they bought blocks of seats all over the stadium and had people stand up holding signs with AIDS messaging. That’s big when you consider it was at Shea Stadium on May 4, 1988, “Women’s Day,” and being televised to millions of people. They also managed to get AIDS messaging onto the electronic sign boards. People were handing out AIDS literature. Why is that not known?

Esther McGowan: A film project we created for Day With(out) Art a few years ago called COMPULSIVE PRACTICE has some great examples on video of women doing amazing activism at the time.

COMPULSIVE PRACTICE (2016)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

Sur Rodney (Sur): Holly Hughes said to me once, “You know, if all the men who are writing about this cultural stuff and AIDS were to shut up for 10 years and only women and people of color wrote about this it would shift things so much. Let these other voices come out because white men have completely dominated the field!”

Esther McGowan: This is a moment where people are looking back at the history of HIV and AIDS. Students and members of the public come to research our archive and are seeing it through a lens of history that suggests that somehow it is over. One of our mandates is to remind people there is still an ongoing AIDS crisis. We celebrate the history of AIDS activism as an incredibly powerful thing. It is probably the most successful activist movement because they created real change. They got drugs into bodies. They were able to get what they demanded in ways that other activist movements haven’t.

Sur Rodney (Sur): Back then when someone had AIDS and was sick they would have Kaposi’s sarcoma all over their body. Anyone that was wasting away, even if they didn’t have AIDS, was seen as having it. Now, everyone looks fairly healthy. Also, we live in New York and it’s a bubble. But when you leave it’s a very different story, particularly in the South. Those communities are isolated and the media in general isn’t really interested in that story. Other than magazines like POZ, A&U and what Visual AIDS is doing, you don’t really hear about it

Rehan Ansari: Is this a difficult time or an easier time to do political art and make allies?

Esther McGowan: It’s an interesting moment, and social media has changed things in a good and a bad way. The way information is shared now, people know in five minutes that a new law has been passed. They get out in the street or show up at the airport to help undocumented immigrants. But at the same time there’s a certain false quality to the idea of activism because if you are sharing information, posting a picture, liking someone’s picture, are you really having an impact, an activist impact? Social media is so much about the visual, that it’s actually a way that art can be shared and used in a more impactful way. We want to encourage people not to engage in superficial forms of activism but think about a balance between using social media and getting out in the street.

Alex Fialho: Our program ALTERNATE ENDINGS features seven minute video commissions from six community-based organizations and collectives that are doing really important on-the-ground work around HIV/AIDS. We are taking this particular direction around activist-focused work at Visual AIDS. We’ve commissioned ACT UP New York; the SERO Project; Positive Women’s Network; The SPOT; Voices of Contemporary Activists and Leaders, (VOCAL); and the Tacoma Action Collective. We’ll compile the films by these groups into one program and distribute.

ALTERNATE ENDINGS, ACTIVIST RISINGS (2018)Courtesy of Visual AIDS

Esther McGowan: We have some legendary artists who worked in activism and who are in our community. Gregg Bordowitz, Avram Finkelstein, Marlene McCarty are people we can approach to seek their advice or collaborate and work with them on a project, as we’re doing with Avram.

Alex Fialho: The backbone of our organization is the Artist+ Registry so programming is centered on artists living with HIV or the legacies of those passed from AIDS. Most of these organizations that we’ve commissioned for a Day With(out) Art, for example, are led by artists or activists living with HIV and those perspectives.

Rehan Ansari: Could you give some examples of what you have learned from an older generation of artists?

Esther McGowan: When I became Executive Director I was trying to think through what my impact could be and my thought was needing to be more activist. So I spoke to Avram about doing YOU CARE ABOUT CRIMINALIZATION (YOU JUST DON’T KNOW IT YET) and we talked about what is effective. Avram co-created SILENCE=DEATH in the ’80s and has amazing strategies from years of experience around how you activate a public space. First you have to make the art, you have to figure out how the art shares the message in different ways. Is there a visual that that resonates? Then how do you activate it? In this instance, we decided it was the Pride march. We make a a broadside around a contemporary topic annually.

Rehan Ansari: And what about an example of where where someone older says, ‘Oh, I’ve learned something from the new generation’?

Esther McGowan:The obvious example is how to use social media. Through having their work online a lot of Artist+ Members, who are long-term survivors, are actually learning how to share through social media.

We talk about ways that the younger generation of people living with HIV, and the long-term survivors of the older generation, can come together to understand each other around issues of different types of medication or prophylaxis, like PrEP. PrEP has created a big disconnect between the generations because a younger generation now knows there’s a pill they can take which changes how you think about HIV, whereas the older generation that has lived through the AIDS crisis, want to educate the younger generation about what HIV and AIDS is and what it can mean.

Sur Rodney (Sur): The younger generation have a very different environment they can work in because they have this PrEP pill and nothing is so terrible, they don’t see people wasting away anymore. The older generation feels that the younger generation doesn’t really understand the pain that we’ve been through.

Alex Fialho: I’m from a younger generation and I’ve been impacted immensely by the conversations that I’ve had with people who were working, living, dying and having sex during the ’80’s and ’90’s. I think an engagement and an interest in people’s histories is really important. Pain and sacrifice are overlooked and holding space for conversation involving emotions is important for me. I think that the older generation is conscious that a younger generation, is going to be what’s here when they’re not here, and we can steward legacies moving forward.

Sur Rodney (Sur): In the ’80’s gay artists were very much a vibrant part of the arts community whether dance or music and anything else. When AIDS happened the pandemic was associated with homosexuality so gay artists became pariahs because of the fear of them as carriers of infection and shame, their work was pushed to the background. The generations that came afterwards don’t know anything about the existence of this work. There was a whole period of de-queering in the ’90’s. I was writing captions for artworks in collections then and I was asked not mention anything about AIDS because the message was “We don’t want to hear that and would you talk about it in some other more general way without mentioning AIDS?”

Sara Reisman: Universalize it?

Sur Rodney (Sur): Yes. They’re doing that with Felix Gonzalez-Torres. They will not include him in anything that has to do with AIDS. The estate feels that if you talk about him and AIDS then he’s getting thrown into this one thing and you’re missing the message of his larger work. What will that mean for the future when historians will only defer to what’s evident in the discourse dominated by the estate and his history around HIV/AIDS is erased. There was a fracture with people not wanting to talk about AIDS and fear of gay people and the feeling they shouldn’t be a part of our cultural history and this fracture is being repaired now.

The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation believes in art as a cornerstone of cohesive, resilient communities and greater participation in civic life. In its mission to make art available to the broader public, in particular to underserved communities, the Foundation provides direct support to, and facilitates partnerships between, cultural organizations and advocates of social justice across the public and private sectors. Through grantmaking, the Foundation supports cross-disciplinary work connecting art with social justice via experimental collaborations, as well as extending cultural resources to organizations and areas of New York City in need.

Founded in 1988, Visual AIDS is the only contemporary arts organization fully committed to raising AIDS awareness and creating dialogue around HIV issues today, by producing and presenting visual art projects, exhibitions, public forums and publications—while assisting artists living with HIV/AIDS. Visual AIDS is committed to preserving and honoring the work of artists with HIV/AIDS and the artistic contributions of the AIDS movement.

Comments

Comments