Introduction by Walter Armstrong:

Bearing witness to the AIDS catastrophe of the 1980s is not for sissies. Still, we survivors now recognize, in our last decades of life, that our firsthand testimony may have historical meaning or, at least, save our dead from oblivion. Thus, we record.

Some recent popular films have recorded AIDS history as the triumph of ACT UP and TAG, casting the gay community’s awesome immersion in death in an inspirational light. The community’s response has been favorable, almost giddy. Portrayed as heroes, we applaud ourselves.

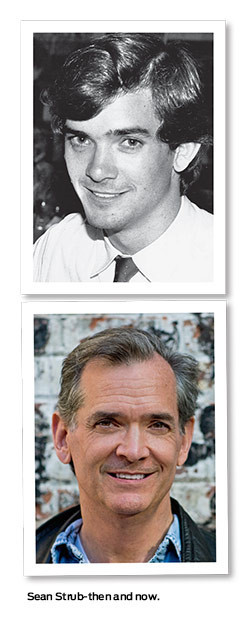

Sean Strub’s new memoir, Body Counts, is a rebuke to this self-regarding version of history. Sean has been known as a major figure in the movement for gay and PWA (people with AIDS) rights for three decades. That is a very long run and a testament to his phenomenal drive and commitment. After founding POZ in 1994, he felt duty bound to fellow PWAs to reflect deeply on the meaning of AIDS, activism and survival. Body Counts is rich with these reflections.

He grew up in Iowa City, the precociously confident and industrious son of a locally prominent family. We learn in Body Counts that at a young age he was given to understand great things were expected of him. Being gay and getting AIDS, of course, were not on the list.

The memoir opens in Washington, DC, where Sean, 17, has arrived to pursue his passion for politics. It is characteristic that he has already talked his way into the center of the action, even if he is merely operating an elevator for members of Congress in the U.S. Capitol. As for gay life, the capital may be one enormous pre-Stonewall closet, but Sean, a bright young thing with black Irish beauty, is much in demand. But realizing that no queer could have a future in national politics, he moves in 1979 to the Big Apple to live as an openly gay man. He meets as many famous people as possible—another Sean characteristic—and is soon taking acid at Studio 54, doing his college homework at the St. Marks Baths and getting infected with HIV. He is 21.

Great expectations have long motivated him to make a dollar while making a difference. In the early 1980s he created one of the first mass-market gay fundraising operations and earned large sums for the decade’s burgeoning gay and AIDS groups, including ACT UP. There he also found a home for his fury at AIDS. This once-devout Catholic’s description in Body Counts of taking mass inside St. Patrick’s Cathedral at the Stop the Church action is an exquisite rendering of the act of protest as a spiritual experience.

Every AIDS memoir is a shrine. Sean pays tender tribute to many diverse friends he has lost, but we learn that Stephen Gendin—an indescribable independent spirit—holds a special claim on Sean’s heart. Stephen was a widely celebrated treatment and prevention activist from 1987, when ACT UP started, to his death at 34 in 2000. He and Sean met selling ACT UP T-shirts for the fundraising committee. Over the next 12 years they became business partners, comrades in arms and closer than brothers. Stephen’s electrifying columns in POZ, most notably in praise of (safe) barebacking, attracted controversy and even censure. But Stephen was recording his own testimony from inside the AIDS maelstrom, mining the deep vein of radical sexual ethics in the bedrock of gay liberation.

Sean’s account of his despondence after Stephen’s death is harrowing. Fierce emotions accompanied the outrageous fortune of witnessing the destruction of almost half of our generation’s young gay men. But what may be most striking about Body Counts is Sean’s unflagging optimism and its embodiment in action. Every venture is an adventure, including his near death in 1995. Body Counts ends after Sean has launched the Sero Project, classic self-empowerment for the “viral underclass” criminalized by unjust HIV-specific laws.

How he keeps his idealism alive is this memoir’s message. But Body Counts has another message, one intended to disrupt the ACT UPism dominating the current AIDS accounting. Sean has long championed the first PWAs who came out in 1982, who sounded the alarm about promiscuity while handing out condoms at bathhouses, and who stared down stigma, defied death sentences, shared support for survival and, above all, drew up The Denver Principles, the original bill of PWA rights and responsibilities. But Sean’s case against ACT UPism is not simply that the earlier pioneers deserve more credit. He also asks whether the emergence of ACT UP may have aborted the potential birth of a more radical lifesaving activism.

His speculations are too specific to summarize here. They turn on the dramatic differences in strategy practiced by the two groups to speed drugs into bodies. ACT UP was focused externally, confronting federal agencies and pharma. By contrast, early activism was focused internally, expanding from PWA rights to prevention, treatment and research. This vision, partly spearheaded by Joseph Sonnabend, MD, depended on a self-confident gay community, with its massive number of motivated PWAs as leverage, negotiating control of the AIDS agenda. By contrast, ACT UP exploited the dominant institutions’ levers of power to win a place, for a few, at the table.

Unsettling insights are the reward for exploring this alternate reading of history. As a PWA, Sean has always rejected the label of victim. Now, as a survivor bearing witness, he rejects what he views as the equally offensive label of hero. For those survivors who wish to add their firsthand testimony to the growing record, Body Counts leaves no doubt that this is the necessary point of departure.

—Walter Armstrong was arrested 14 times with ACT UP and did almost 10 years at POZ, including eight as editor-in-chief.

Excerpt from Body Counts by Sean Strub:

Most of my life, I have been interested in both business and activism, even when it has been morally and financially tricky navigating between them. The middle space I straddled sometimes left others unsure if I was fish or fowl, activist or capitalist.

Business partners occasionally questioned whether my decisions were in the interest of business or to advance my political agenda. Some activists resented a for-profit business within the movement, and when I was raising money for GMHC and ACT UP I was criticized—generally behind my back—for “exploiting,” even “getting rich on,” activists and people with AIDS. Even though that criticism rarely came from PWAs, I was sensitive to it. I tried to take pride in what our work made possible, rather than feel the pain of personal criticism.

It was my mortality that gave me the freedom to take financial risks and invest in the LGBT and HIV/AIDS communities. Vito Russo used to tell me that to be a successful lifelong activist, I needed to have some financial security; he said he regretted not having focused more on that goal when he was young.

I’ve also had friends, including some who are affluent, who have supported the causes and projects I’ve been involved with over the years, as both donors and investors. In retrospect, I think “campaigning”—whether for myself, others or a greater good—is my natural mode of being.

I’m proud that many people with HIV and gay men learned practical, detailed information they needed to stay alive from the 12 million fundraising letters that my firm produced for AIDS-related clients in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Those fundraising letters reached more gay men than any gay community publication at the time; for some who didn’t read LGBT media, or live in big cities, our fundraising letters were an important connection to a community.

With the fundraising business, the card packs, producing the play The Night Larry Kramer Kissed Me, as well as POZ and other enterprises, I used for-profit endeavors to pursue a political agenda. My life had become consumed with a mission rather than a quest for a career, always shadowed by the likelihood that I would die of AIDS.

Once the epidemic had been around me, but not of me. Then it became of—and in—me, though I fought to keep it from defining me. By the early ’90s, it was impossible to separate any part of my life from HIV. There were few distinctions between my personal and professional lives. It is no surprise some found that concerning.

The epidemic, and specter of my own death, was a constant presence, precluding any long-term plans beyond the next demonstration, fundraiser or funeral, but at the same time it also energized me with purpose and projects. Ironically, as my health was starting to fail, I was still starting new businesses.

AIDS spawned a “viatical settlement” industry that speculated with the life insurance policies of those who were defined as terminally ill and expected to die soon. Instead of the policy’s death benefit going to a designated beneficiary of the deceased’s estate, the policyholder could sell it while he or she was alive, at a discount calculated based on expected longevity, and receive the cash to use as they pleased.

I had two policies, one from Chubb and another issued by New York Life, with a combined death benefit of $450,000. The viatical company required my medical records for a doctor to analyze, an extensive questionnaire, and a visit to its doctor before it made me an offer. I sold the policies for $345,000 and used the proceeds, along with my savings and credit card advances, to launch POZ. Not everyone close to me thought it was such a great idea; there was concern from friends and family I was suffering AIDS-related dementia.

The idea of a glossy lifestyle magazine for people with AIDS was not universally well received. But I was sure that as soon as we produced it, the doubters and naysayers would understand. Before he read the first issue, Leonard Goldstein, a gay neocon political columnist for the New York Native, said that people with AIDS starting a magazine called POZ was like Holocaust victims starting a magazine called GAZ. A joke making the ACT UP rounds was that POZ would feature fashion spreads of what to wear at your own funeral.

I initially titled the magazine Life Plus, but when I got a letter from an attorney for Time-Life claiming it violated their trademark, we went back to the drawing board. One day I was talking with my friend Matt Levine about someone we’d both recently met; he inquired about the person’s HIV status, asking, “Is he a pozzie?” “That’s it: POZ!” I said. “We’ll call the magazine POZ!”

Initially, the name required explanation, as people didn’t understand that it was a less clinical way of saying “HIV positive,” as well as a double entendre for thinking or acting positively, which was a big part of the magazine’s message. The word “poz” has since entered the vernacular.

Our initial business model relied on a mix of subscriptions and advertising; this, too, raised doubts. One trade publication made a crack about readers not living long enough to renew subscriptions. Sam Watters, owner of The Advocate, told Ad Age that he doubted the prospects for POZ: “What advertiser would want to advertise in a magazine on such a grim topic?”

I envisioned POZ as a general-interest magazine reflecting the way we lived our lives with AIDS—pursuing careers, falling in love, raising our children, everything life entails—not just the death and dying that defined us in mainstream media. POZ would look at the entire world—politics, economics, culture, fashion and arts—through the prism of the epidemic. We weren’t afraid of humor, either.

We would skip the insider jargon of treatment wonks and the stereotypical victimization of people with HIV. Activist rhetoric had created a vocabulary that mapped out the political dimensions of the epidemic as a function of homophobia and created a language for people with HIV to identify with community, empowerment, resistance and pride. The urgency of the epidemic had forced an unprecedented level of honesty when talking about sex, within the LGBT community and society at large, which was reflected in POZ.

POZ also translated complicated science and factors that affected treatment decision-making into messages our readers could understand, even while that science was changing rapidly. In 1994, the year POZ started, the Food and Drug Administration was still approving HIV medications for monotherapy (a single drug treatment), but within two years, triple-combination therapy (three different antiretroviral drugs) was the gold standard and monotherapy was considered dangerous.

We tried to tell the story of the epidemic in all its complexities, through the experience of those with HIV. And we would do so in an attractive, engaging and hopeful format—on glossy paper.

To launch POZ, I knew I needed help. I scoured my Rolodex and reached out to a wide-ranging roster of contributors, especially those who had articulated or depicted the rich and sophisticated discourse the AIDS community had created in the culture to deal with the epidemic.

We encouraged them to write about what interested them the most. Some were well established, even famous; others were unknown, and we provided their first byline in a national outlet. Writers such as David Feinberg, Kiki Mason, Scott O’Hara and others took uncommon risks and expressed powerful emotions, as they knew they were approaching the end of their lives.

[My then-partner] Xavier Morales had moved in with me early in 1993, and he was integral to the magazine’s launch in 1994, creating and maintaining the initial database of subscribers and contributing to editorial and marketing discussions. Calls to the magazine rang on our bedside phone after hours, so we took subscription calls late at night, but often there were calls from people newly diagnosed, concerned parents or frightened partners wanting information or someone to talk to.

We sometimes went to bed while staff members were working late into the night. As the company grew, we took over the entire building—three floors plus the sleeping loft—as well as part of an adjacent building and a small space around the corner on 14th Street [in Manhattan].

There was little division in those days between the private lives Xavier and I led and our work with the magazine; the same was true for many of our staff members. There was never any concern about people showing up late or leaving early. For the next several years, nothing else in our lives matched the urgency and importance of what we believed we were doing with POZ.

When the first issue of POZ hit newsstands and mailboxes around the country in April 1994, I was sick with a mild case of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The stress leading up to the launch caught up with me, and I was confined to my bed. But that didn’t lessen my excitement and pride in our first issue.

Kevin Sessums, Vanity Fair’s top celebrity interviewer at the time, wrote the cover story, profiling Ty Ross, a fetching young gay man with HIV. What made Ty a cover candidate was his famous grandfather Barry Goldwater, the conservative 1964 Republican nominee for U.S. president.

We flew Kevin to Los Angeles to spend several days with Ty, and they hit it off so well that they became intimate with each other. Sessums, who was HIV negative, wrote beautifully about the encounter, using it to explore the common but mostly irrational fear of having sex with people with HIV.

Kevin was already well known, and Ty’s famously conservative Republican grandfather was as far removed from the popular impression of AIDS as he could be. That, combined with Kevin’s writing and the peculiarity of a magazine for people with a “terminal illness,” made for a perfect media storm. Sexy photos of Ty, taken by Hollywood photographer Greg Gorman, only added to the news appeal.

Kevin was criticized from some quarters for sleeping with his interview subject, but the profile was a masterful first-person account that I was proud to present. I wanted POZ to directly confront the popular notion that people with HIV should never have sex again after their diagnosis; a profile of someone attractive and detailing his encounter with someone who did not have HIV was perfect.

We also profiled [activist] Tom Keane in that first issue, reflecting on his role at the St. Patrick’s Cathedral demonstration when he “snapped the cracker.” Donna Minkowitz interviewed [Clinton aide] Bob Hattoy about the White House. David Feinberg wrote the first sex column, and David Drake contributed a tribute to [activist] Michael Callen, who had died a few months earlier. Mark Schoofs contributed a media column about coverage of AIDS in The New York Times; he went on to win a Pulitzer Prize for his AIDS coverage in the Village Voice and subsequently covered the epidemic for The Wall Street Journal.

Our first editor, Richard Perez-Feria, was up-and-coming in the industry and recommended to me by Sessums. Perez-Feria enlisted veteran magazine designer J.C. Suares, who created a striking visual identity for the magazine, with lush photography and illustration.

When I got sick as the first issue was coming off-press it marked a new phase in my relationship with [my friend] Stephen Gendin. He was taking an ever-growing amount of responsibility in my company, but we had never specifically addressed what would happen in the event that I was incapacitated or died and whether Stephen was a candidate to take over.

When I got PCP, he wrote me an uncharacteristically emotional letter. “I feel as though I’ve been in shock for the last two hours, and my hands haven’t stopped shaking,” he began. “I’m very concerned about you and, although I don’t often express it, I care for you very much…. I want to let you know how happy I’ve been working with you over the last four years. I just can’t imagine working anywhere else.” His letter meant a lot to me, especially hearing that he was there for the long haul. As his commitment became clear, the dynamic between us became more like a partnership.

I got over the PCP in a few weeks and, by early summer, was again working long hours. I thought it unlikely that I would live to see the magazine to profitability, but I was determined to be around long enough to see it earn respect. I was looking for respect as well: I wanted my work and role as an activist to be as widely recognized as my work as an entrepreneur.

The media response to the launch was overwhelmingly positive. Frank Rich, in his New York Times column, said POZ was “easily as plush as Vanity Fair” and “against all odds, the only new magazine of the year that leaves me looking forward to the next issue.” POZ became a player in the national discourse on AIDS, often as a watchdog but sometimes as a provocateur.

With our skeptical treatment philosophy, we broke news about drug side effects, the emergence of resistant viruses, and the suppression of those developments by drug companies. With our ear to the ground in the gay community, we were the first national media to use the word and report on the “barebacking” phenomenon, cover prevention strategies beyond condoms, and write about the crystal-meth addiction that was fueling a rise in HIV infections. We exposed the public health message that women could easily pass the virus to men as a myth.

Also, by giving visibility to individuals with “star” potential—people with HIV doing groundbreaking work—we helped advance careers in activism, health policy and the arts, and create a new generation of AIDS leadership.

Some critics argued that POZ presented people with HIV in such a positive light—and in such a visually appealing format—that we were “glamorizing” having the disease. Some even accused us of making HIV seem desirable. Others accused us of making the use of condoms less urgent, or leading readers to become less compassionate about people with HIV or less generous in their charitable support.

There was admittedly an inherent dichotomy between empowering people with HIV—letting them know they had full lives to lead—and fear-based HIV-prevention messaging, which heightened stigma and depicted HIV as the worst thing that could possibly happen to a person. Every time we profiled someone with HIV who was good-looking, successful, happy or optimistic, some saw it as undercutting that dire message. But that criticism seldom came from people with HIV.

Editorial meetings were the most rewarding part of running the magazine. I wanted to hear different opinions—to learn about the other side of any issue—and I enjoyed the vigorous back-and-forth as we debated editorial priorities.

Walter Armstrong, our editor-in-chief from 1998 to 2005, had been a member of ACT UP and a veteran of Outweek and QW, two New York gay newsweekly magazines, and had co-founded AIDS Prevention Action League (APAL) with Stephen. He brought an irreverent yet critical style to the magazine that reflected the rich language that had developed in the culture to cope with AIDS.

Walter and I didn’t know each other in ACT UP. We met initially through Stephen, who had hired him as a writer. We shared similar backgrounds, which strengthened our connection, especially when we discovered that his Haverford college roommate was a childhood friend of mine from Iowa. But it was our differences that created a complementary balance.

My monthly “S.O.S.” columns [a play on my full name: Sean O’Brien Strub] were made more eloquent and meaningful with Walter’s editing and, in the process, he inspired me to think more critically about the epidemic, the magazine’s responsibility, and our readers’ wants and needs. He has sometimes characterized me as a mentor to him, which I find flattering, but the truth is we had—and continue to have—a mutual mentorship.

He rarely has gotten the credit he deserved for the magazine’s successes, partly because of his innate modesty and distaste for the spotlight, but also because of his HIV-negative status.

Understanding the relationship between people who had HIV and those who did not was at the core of what many found so meaningful, inspiring and even disturbing about POZ. Suares and a number of the editors—Richard Perez-Feria, Esther Kaplan, Laura Whitehorn, Lauren Hauptman, Sally Chew, Bob Lederer and others—and business staff central to the magazine’s success, including my sister Megan, were all HIV negative but profoundly affected by AIDS.

POZ was a way for people with HIV to get together, in its pages, every month. We did our best to facilitate that magic.

An excerpt from Body Counts: A Memoir of Politics, Sex, AIDS and Survival by Sean Strub. Copyright 2014 by Sean Strub. Reprinted with permission of Simon and Schuster, New York, NY. All rights reserved. Click here to purchase the book.

4 Comments

4 Comments