It was November 2013 when Miguel Anaya, an immigrant from Sinaloa, Mexico, slipped and fell at one of his many day labor jobs in Birmingham, Alabama. He had been living in the United States for 13 years with no family, no health insurance and no financial back-up plan. To make matters even more desperate, while he was in the emergency room awaiting life-saving treatment, Anaya was told—in broken Spanish—that he had HIV. “My initial reaction was surprise. After that, it was depression, because I didn’t know what to do next,” he recalls. Soon after his diagnosis, the 57-year-old construction worker and painter faced homelessness, unemployment, hunger and disability, all at the same time.

Anaya’s story is the kind of “perfect storm” that many folks working to combat HIV/AIDS in the South face on a regular basis, says Kathie Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama, one of the region’s largest AIDS service organizations. Black, Latino, poor and increasingly rural populations are facets of the epidemic that are rarely reported in the mainstream news or discussed at U.S. decision-making tables.

“If you look at the South as a region, it’s by far the poorest part of the country,” says Hiers, a 30-year veteran of the region’s HIV/AIDS fight. “But now that the epidemic has shifted, nobody wants to give up a dime to help us or our clients.”

Today, the nine states comprising the traditional “Deep South”—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas—account for nearly 50 percent of new HIV cases in the country, despite making up just 28 percent of the U.S. population. The region also includes nine of the 10 states with the highest AIDS mortality rates. Specifically, 27 percent of people with AIDS die within five years of being diagnosed.

However, just one year after Anaya’s accident, he’ll tell you that he’s one of the lucky ones. The aspiring advocate is now housed, fed, educated about HIV and, literally, back on his feet—one prosthetic and one his own.

That’s where AIDS Alabama’s Living Well program comes in. “They accompanied me to all of my medical appointments, educated me about the importance of keeping my appointments, translated the instructions of every medicine,” Anaya says. He was one of the first enrollees in the brand-new pilot project, established at AIDS Alabama in 2014 through an experimental grant from AIDS United.

Living Well is a two-year study that links a dynamic team of HIV-positive health workers, or “Peer Support Specialists,” with AIDS Alabama’s newest, most at-risk clients. These peers talk clients through their struggles and walk them through everything they need to know to live healthy with HIV. The study’s end goal is to prove that this new kind of highly individualized HIV program is faster than existing health outreach models at getting people connected to care, adherent to their medications and living independently.

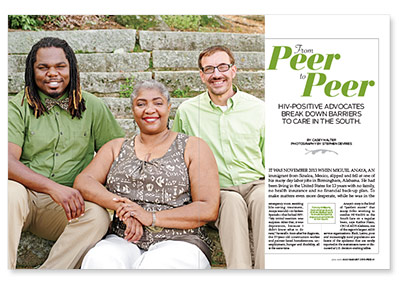

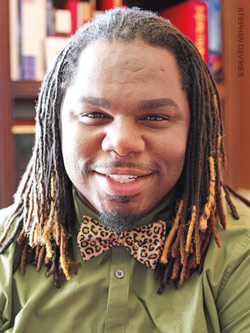

Together, peers such as Andrew Ballard, Debra Richardson and Tommy Williams, profiled in this feature, along with the help of their staff supervisors at AIDS Alabama, are revolutionizing the way people in the Deep South are able to access HIV care. Their peer retention-in-care model is helping create a blueprint for organizations in the new epicenter of the epidemic, teaching them how to use scant resources as efficiently as possible and how to help their clients overcome seemingly insurmountable barriers to enjoying healthy and independent lives with HIV/AIDS.

|

| Debra Richardson |

“I often say that HIV is a symptom of the problems our at-risk communities are facing. It comes from racism, social injustice, a lack of access to education, and these broken health systems we have in the South,” says Dafina Ward, the chief prevention officer at AIDS Alabama, who works with Kathie Hiers to stem the tide of new HIV cases in the state. Ward, who originally wrote the proposal to get AIDS Alabama’s Living Well program off the ground, reaches out to more than 10,000 people living with and at risk for HIV across the state every year.

Currently, none of the nine states in the Deep South has expanded its Medicaid program under the Affordable Care Act, leaving thousands without access to health insurance. The gap in coverage leaves Alabama alone with an estimated 1,900 of its lowest-income HIV-positive residents completely uninsured. State health department statistics show that as much as 40 percent of its Latino population and 15 percent of its African-American population are living without access to affordable health care.

The South is also an epicenter of abstinence-only sex education. Despite this—or because of it—the region also leads the national ranks in terms of teen pregnancy, with 75 percent of Southern high school seniors reporting being sexually active. Add in extensive inequality issues regarding poverty and racism—a black man today is 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than a white man in Alabama; a Latino man is five times more likely—and it becomes a perfect storm for infection and proliferation among at-risk communities.

All of these combine to create what the Living Well program defines as “barriers”—things that stand in the way of people taking charge of their health and staying in care after an HIV diagnosis, explains Ward.

These barriers include a lack of regular transportation to get to doctor’s appointments in a region where public transit systems are few and far between. Another issue is providing housing for an HIV-positive population where, according to a 2006 Columbia University survey, 60 percent of those diagnosed with the virus report being homeless or having unstable housing at some point in their lives.

“The program grew out of a need that we found while talking to our colleagues at local clinics,” Ward explains. “At the time we wrote the grant for Living Well, one clinic we were working with had about 1,000 clients living with HIV and had a 50 percent no-show rate for their appointments. We realized we could do things with patients that the clinics didn’t have the time or resources to do.”

As of now, Birmingham as a city ranks 17th in the nation in terms of the number of new HIV cases. In 2012 (the latest year comprehensive health data was documented in the state), 61 percent of the state’s more than 12,000 HIV-positive people were not connected to care.

Debra Richardson, one of three HIV-positive members of the program’s peer support team, explains further: “The purpose of peer mentoring is ‘I was where you are: When I was diagnosed, I had questions and I didn’t know who to ask. Then, when I got to the person who had the answers, I was asking them the wrong questions.’”

Richardson has been with AIDS Alabama since 2006. She started out as a client, in long-term recovery from substance abuse after being diagnosed with HIV in 1995. When she came to the organization, Richardson was homeless and unemployed and she needed help from AIDS Alabama to pay the bills, get back on her feet and take care of her children. By 2011, the mother of five, grandmother of 10, great-grandmother of one and survivor of open heart surgery had bought her own house and begun advocating for other HIV-positive people. By 2014, she was hired as a peer mentor at Living Well.

Every day, Richardson and the other peer mentors work with about three to five AIDS Alabama clients, supporting about 30 to 40 clients each throughout the course of a month.

Most of what they do, explains Richardson, is transport other HIV-positive people to and from their doctor’s appointments, often with their own cars, driving hours to some of the region’s most rural areas. Sometimes peers pick up HIV prescriptions and deliver them to clients’ houses. Other times, AIDS Alabama peers are simply there to lend a supportive ear to those in need.

“When I was diagnosed, I really didn’t have anybody to talk to,” says Andrew Ballard, who joined the Living Well team in 2014 after attempting to navigate the difficulties of an HIV diagnosis in the South, as a gay man, for over 10 years on his own. “It was very lonely. I felt very isolated and didn’t want other people to go through that same experience.”

Sometimes, Ballard says, all it takes to get a client on track is to have a little bit of help filling out medical forms or housing assistance applications. Other times, it’s about calling clients daily to remind them about their medical appointments to get them on course with their treatment.

Ballard was diagnosed with HIV in 2003, while living in North Carolina. Despite all the recent treatment advances and advocacy going on up North, he was completely misinformed by the medical team who diagnosed him. “The doctor basically just walked into the room and told me to get my affairs in order,” Ballard says. “My mom and I were actually discussing suicide because we were under the impression that it was still a death sentence.”

Only after he moved back to Alabama and enrolled in care at the 1917 Clinic did Ballard realize how far HIV treatment advances had come. After starting meds, going through therapy and becoming interested in advocacy, Ballard got the job at Living Well.

“Some of my clients actually said, ‘I was missing my appointments because I just really didn’t care,’” says Ballard, who prides himself on being able to talk people into taking charge of their health. “I know that there is a lot of stigma, especially in the South, and until we get people educated, it’s going to remain.”

Another peer, Tommy Williams, who started working at AIDS Alabama in 2012, says the Living Well program also pivots on reaching out to at-risk communities wherever they are. “I am often paired with clients who identify as LGBT and those who do not conform to labels,” he says. “Before my diagnosis, I played a huge role in discussing HIV issues with anyone who would listen. Now, my disclosure presents a shock factor to all who know me.”

Williams joined the organization through its ELITE Project, which reaches out exclusively to young men who have sex with men (MSM). He’s been living with HIV since 2006. Thanks to his already extensive connections in Alabama’s LGBT community, Williams was able to seek out the help he needed to overcome his own barriers to living with HIV by himself. For that reason, Williams was considered an all-star advocate at the organization. When AIDS Alabama launched Living Well, his staff supervisors thought he would be the perfect fit for the program.

Sherron Wilkes, the retention-in-care coordinator and immediate supervisor of the peers at Living Well, lays out the criteria she put in place for recruiting her inspiring team: “No. 1 is being fully disclosed, not ashamed and not stigmatized. Two is having been able to matriculate through life and overcome their own personal barriers. And three, knowing where all those resources are in the community and knowing how to navigate through the clinic.”

AIDS Alabama partners with eight health clinics throughout the state. The organization is there to take on clients and fill in the care constituency where the state health department social workers cannot. “Our end goal,” Wilkes says, “is to get people to become self-sufficient and independent.”

So far, Living Well has enrolled 127 HIV-positive people into the program, and it hopes to have 200 people in the study cohort by the end of 2016.

|

| Tommy Williams |

“We’re all hanging our hats on the treatment cascade,” says AIDS Alabama’s Kathie Hiers. “No. 1, making sure people know their status. No. 2, that they get into care. No. 3, that they get on ART [antiretroviral treatment]. And No. 4, that they stay adherent to their HIV medication.”

The “cascade” refers to the ever-diminishing percentage of people who make it through the steps of the care continuum Hiers describes. Current Alabama stats (from 2012) show that only about 55 percent of HIV-positive people in the state are linked to care.

Of those, 39 percent are retained in care (meaning keeping up with their medical appointments on a regular basis) and only 29 percent of those retained in care report having a suppressed viral load.

Addressing the continuum shortcomings is a common goal of modern-day HIV/AIDS advocates across the country, and it’s a challenge to achieve—especially for those in the South.

The crux of the HIV care continuum is actually prevention, say the staff members at Living Well. When HIV-positive people are aware of their status, they are far less likely to pass the virus on to others. With a suppressed viral load, their likelihood of transmitting HIV goes down even further.

It’s a theory known in the AIDS industry as “secondary prevention” —targeting people living with HIV, rather than HIV-negative people—and it has proved to help stem the tide of new cases.

“We try to bridge the gap between the care providers and us,” says Richardson. “Yes, you can take our blood, you can put it on the slide, but you also have to treat the person with the blood. Being that we are the ones living with HIV, we try to let the clinics know what we need so we can receive better care.”

Ultimately, the Living Well pilot project hopes to show that the “peer model” can help drastically improve Birmingham’s care continuum stats. Already, they’ve had several clients, including Richardson, “graduate” from AIDS Alabama’s services and move on to a wholly independent life with HIV.

“Our doctors might be great, our social workers might be great, but there is nothing more powerful than an HIV-positive person talking,” says CEO Hiers. “Having gatekeepers into the community makes all the difference in the world.”

It’s also important that gatekeepers reflect the community. Sixty-four percent of new HIV infections in Alabama are among African Americans, despite the fact that they make up just 26 percent of the population. Young, gay African-American men, like Williams, are 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than any other Alabaman. And African-American women, like Richardson, are 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than white women in the state.

There are an estimated 12,000 to 14,000 people living with HIV in Alabama, with up to 2,600 people still currently unaware of their infection. Hiers says the state gets nearly 900 new HIV infections every year, a population Living Well is hoping to seek out and get enrolled into life-saving care and on treatment as quickly as possible.

|

| Andrew Ballard |

In just one year, Living Well has already found 144 of what HIV/AIDS groups consider to be the “hardest-to-find people” living with the virus and got them back into care, says Dafina Ward, AIDS Alabama’s prevention chief. The program did so through advocacy networks and creative collaborations among a multitude of other social service organizations in the region.

AIDS Alabama finds clients for its Living Well program in a variety of places: domestic violence shelters, correctional facilities, substance abuse organizations, the YWCA, youth outreach programs, schools, mental health providers and urgent care clinics, as well as all the other AIDS service organizations in the state, through a tightly knit coalition called ASONA, the AIDS Service Organization Network of Alabama.

Through these collaborations, AIDS Alabama manages to provide an array of services. Whether clients need housing, help with rent or utilities, transportation, GED or vocational training, mental health services, or a link-up to a support group, the peers at Living Well have the connections to a growing community of people who are working hard with tight resources to make ends meet for others. They all share clients, and they all share the ultimate goal of getting people living with HIV back on their feet.

“I wish more states would go toward that kind of model, but everyone’s too damn busy fighting over their money,” Hiers says. “We don’t really have the same level of access to foundations or movie stars, so in addition to the federal funding being less, and the state funding being less, it’s hugely inequitable.” Through the ASONA coalition, AIDS Alabama, along with more than 100 staff members, has managed to establish some sort of HIV outreach in all of Alabama’s 67 counties.

The Living Well program will continue through 2016, until the grant money from AIDS United runs out. However, the staff at AIDS Alabama say they are already saving money and putting forth plans to continue on long after that deadline.

“Things are changing; we are in the New South, and there is a new wind blowing,” says Ward. She hopes that with the support of peers, as well as the social justice and LGBT movements they’re so deeply involved with, AIDS Alabama can help expand the program’s goal even further.

“We need a united front in fighting for justice for everybody. We are all in the same boat, and we won’t end HIV without addressing all of that,” she adds.

In fact, AIDS Alabama recently got a big grant from pharmaceutical giant Gilead Sciences to begin a seven-month program to certify their peers as licensed social work professionals. The grant will also train others to do their job across the South. Richardson, Williams and Ballard are all enrolled in the new mentoring program, as is Living Well client Miguel Anaya.

“I want to be able to help others like me in the Latino community to overcome barriers and discrimination,” says Anaya, inspired by the work of his friends at Living Well. “My only family is AIDS Alabama, and my peer mentors and I will never forget what they did for me.”

3 Comments

3 Comments