No matter how you look at it, HIV disproportionately affects African Americans more than any other group. However, Latinos are next in line. The media, AIDS service organizations and HIV providers—as well as the Latino community—often overlook the simple fact that the virus also heavily affects Latinos.

Latinos represent about 16 percent of the U.S. population, but they account for about 21 percent of all new HIV cases across the country. Although the overall levels of new HIV cases among Latinos have remained stable for the past decade, the details and shifting nature of the epidemic in this population give us reasons for concern.

Two examples: There’s the continuing occurrence among Latinos of “late testing”—developing AIDS within 12 months of an HIV diagnosis. And then there’s the fact that HIV rates among Latino gay and bisexual men are increasing at an alarming pace. These combined factors lead to a sobering question: Are Latinos the next wave of the epidemic?

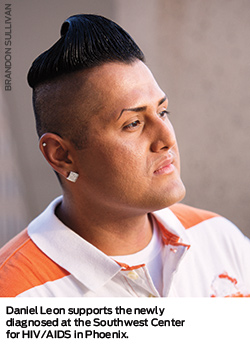

Daniel Leon’s story is a reminder of the toll that Latino culture—in most respects, something that’s a source of pride and comfort—can take on the health of its people. As a Mexican American, Leon grew up with strong women. With no father figure in the picture, his mother and three sisters were his role models. He had male cousins in his large Latino family, but he couldn’t relate to them. He knew at a young age that he was different—and it showed.

“I’ve been an outcast for as long as I can remember,” Leon says. Without intentional malice, his own family members were the first ones to taunt him. Elementary school was even more torturous than his home life. He planned his escape each day to make it home without seeing anyone who wanted to pick on him.

As Leon got older, he realized that he was attracted to men. He reached out to an openly gay student at his high school. Within a day of the two boys hanging out, he returned to school only to find out that word had spread. “I heard someone yell ‘faggot’ at me and realized people were spitting at me,” he says.

The people yelling and spitting at him were once his close male friends. “I was a sinner in their eyes,” Leon says, referencing the strong influence of religion in Latino culture. After that, he started using recreational drugs, which he says allowed him to escape and lowered his inhibitions. Days before he turned 23 years old in 2006, he went to the emergency room after having chest pains and coughing up blood.

At the ER, he tested HIV positive. “When I let out a scream and began to cry, I was quickly shamed by the doctor for doing so,” Leon says. His family didn’t provide much comfort. “I knew they were talking about me,” he says. “I felt it when their embraces weren’t as tight as they had always been.”  His neglect of his health, even before seroconverting, kept Leon in and out of the hospital for years after his HIV diagnosis. One day while he was in the hospital, a cousin told him he looked like their grandfather, who died of cancer. At that moment, Leon decided he didn’t want to be that person everyone felt sorry for.

His neglect of his health, even before seroconverting, kept Leon in and out of the hospital for years after his HIV diagnosis. One day while he was in the hospital, a cousin told him he looked like their grandfather, who died of cancer. At that moment, Leon decided he didn’t want to be that person everyone felt sorry for.

“My first step was eating a Mexican burrito I made my mom bring to me,” he says, “and those things aren’t small!” He educated himself on HIV at the Southwest Center for HIV/AIDS in Phoenix and improved his health and outlook. Today he is a spokesperson for the agency, providing much-needed support to the newly diagnosed.

Gay and bisexual Latino men account for nearly four out of five new HIV cases among Latinos nationwide—and more than a third of them in 21 major U.S. cities are unaware they have the virus. The data suggest an urgent need for HIV testing in this group, especially among the youth. About 70 percent of HIV-positive Latino gay and bisexual men between the ages of 18 and 24 don’t know their status.

These stark statistics spurred the creation of a new initiative by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Reasons/Razones” is a national, bilingual campaign to promote HIV testing among Latino gay and bisexual men. These men can help “break the cycle of HIV in their communities by getting tested and knowing their status,” says CDC spokesperson Lorrie Alvin.

The CDC isn’t alone in its concern about the rising HIV rates among Latinos, especially for gay and bisexual men. “In 2009, for the first time the number of new infections among Latino gay and bisexual men surpassed the number of new infections among African-American women,” says Daniel Montoya, deputy executive director of the National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC).

As a result, Latino gay and bisexual men are the third most heavily affected population and black women are now the fourth. White and black gay and bisexual men remain first and second. Between 2009 and 2010, the estimated new HIV cases among Latino gay and bisexual men increased by more than 10 percent.

Another cause for concern is late testing. More than a third—36 percent—of Latinos living with HIV were diagnosed with AIDS within a year of testing positive. By comparison, 32 percent of whites and 31 percent of blacks tested late.

“Looking across the spectrum from HIV diagnosis to viral suppression—the point at which the virus is under control and a person can remain healthy and reduce the risk of transmission—reveals missed opportunities for reaching Latinos,” says Jorge Zepeda, manager of Latino programs at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation (SFAF).

The reasons for such a high rate of late testing vary. “Latinos may be particularly difficult to reach due to language and sociocultural specifications not often addressed in HIV prevention, in linkage to HIV care and in supportive services to increase retention in HIV prevention programs and care,” says Zepeda.

The Latino programs at SFAF try to bridge these gaps by providing culturally appropriate services for nearly 300 people living with HIV/AIDS and their families. Facilitated by bilingual staff, SFAF provides Latinos with a range of support, including treatment education, health literacy, client advocacy, case management, systems navigation, linkage coordination and peer support groups.

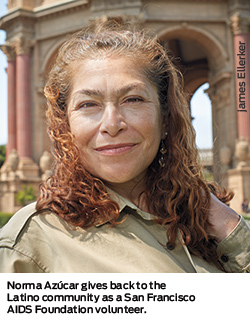

Gay and bisexual men are certainly not the only Latinos affected by the virus. In recognition of that fact, in addition to its Reasons/Razones initiative, the CDC is developing a new HIV testing campaign for all Latinos as part of its Act Against AIDS multi-year awareness program. Norma Azúcar’s story is a case in point. After her husband died in 1994, she sank into a depression and started using injection drugs. It wasn’t until 1998 that she voluntarily admitted herself into a rehabilitation facility.

Norma Azúcar’s story is a case in point. After her husband died in 1994, she sank into a depression and started using injection drugs. It wasn’t until 1998 that she voluntarily admitted herself into a rehabilitation facility.

It was in rehab that Azúcar learned that she was coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C. “I shared syringes while injecting heroin,” she says. “Although I thought I had cleaned them well enough, I still got infected.”

After 15 years of being HIV positive, the 56-year-old Salvadorian has significantly changed her life. Using her degrees in contemporary Latin American literature from Columbia University and in business administration from San Francisco State University, Azúcar is giving back to the Latino community as an SFAF volunteer.

“There is so much ignorance, shame and stigma among Latinos regarding HIV,” she says. Azúcar believes in empowering youth with HIV education and the skills to come out to their parents. As a health promoter, she encourages all Latinos to get tested for HIV.

There remain many concerns when it comes to Latinos and HIV, but a major change in U.S. health care has the potential to alleviate some of those concerns, especially access to care. The Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. the health care reform law, or ACA) begins full implementation as of January 1, 2014.

The expansion of Medicaid nationwide, although not uniformly because some states have chosen not to participate, will help millions of Latinos, many living with and at risk for HIV. Despite this improvement, undocumented immigrants remain ineligible for expanded coverage. That means millions of undocumented Latinos—again, many living with and at risk for HIV—will continue without access to health care.

“Providing legal status and access to the coverage systems created through the Affordable Care Act would go far in bringing these individuals, whose legal limbo leaves them especially vulnerable to HIV, out of the shadows and link them to critical preventive services,” says Moises Agosto, director of Treatment Education, Adherence and Mobilization (TEAM) at NMAC.

The ACA is a big piece of the puzzle, but it will take much more to stem the tide of HIV/AIDS among Latinos. All of the challenges faced by other groups—a lack of AIDS education, HIV testing and access to care, for starters—certainly need to be addressed. However, as given witness by Leon and Azúcar, stigma remains powerful.

The data are inconclusive on whether Latinos are the next wave of the epidemic. Regardless, the epidemic is clearly taking its toll on this population. In the spirit of the Latino Commission on AIDS slogan—“Unidos Podemos / Together We Can”—perhaps stigma and the epidemic can be defeated if Latinos and their allies work together to do so.

Comments

Comments