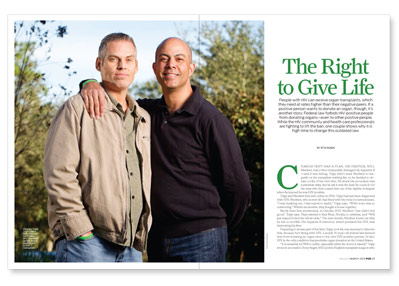

Charles Tripp had a plan. His partner, Will Sherbert, had a liver irreparably damaged by hepatitis B —and it was failing. Tripp didn’t want Sherbert to languish on the transplant waiting list, so he decided to donate a lobe of his own liver. He knew the procedure was somewhat risky, but he felt it was the least he could do for the man who had coaxed him out of the depths of despair when he learned he was HIV positive.

Tripp and Sherbert first met online in 2006. Tripp had just been diagnosed with HIV; Sherbert, who is now 45, had lived with the virus for several years. “I was freaking out. I was scared to death,” Tripp says. “Will’s voice was so comforting.” Within six months, they bought a house together.

But by their first anniversary, in October 2007, Sherbert “just didn’t feel good,” Tripp says. They traveled to Key West, Florida, to celebrate, and “Will just stayed in bed the whole time.” The next month, Sherbert found out why he felt so terrible: His hepatitis B infection, which predated his HIV, was destroying his liver.

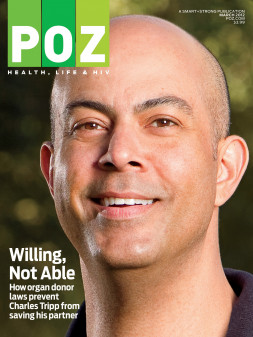

Preparing to donate part of his liver, Tripp, now 44, was stunned to discover that, because he’s living with HIV, a nearly 30-year-old federal law banned him from donating an organ even to his own HIV-positive partner. In fact, HIV is the only condition that precludes organ donation in the United States. “It is senseless for Will to suffer, especially when the donor is myself,” Tripp wrote in an email to Dorry Segev, MD, a Johns Hopkins transplant surgeon who has spearheaded a campaign to overturn the ban—a move supported by the American Medical Association, the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) and a number of other prominent medical groups. “We both understand the risks,” Tripp wrote, “but the outcome could be so promising—and it’s just out of reach.”

“It is senseless for Will to suffer, especially when the donor is myself,” Tripp wrote in an email to Dorry Segev, MD, a Johns Hopkins transplant surgeon who has spearheaded a campaign to overturn the ban—a move supported by the American Medical Association, the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) and a number of other prominent medical groups. “We both understand the risks,” Tripp wrote, “but the outcome could be so promising—and it’s just out of reach.”

If Congress lifts the embargo, organs from HIV-positive donors could be transplanted into HIV-positive recipients. “There are hundreds if not thousands of these organs thrown away every year,” Segev says. He estimates that there are currently 500 potential HIV-positive organ donors in the United States—enough to benefit nearly 1,000 people with HIV in need of a new liver or kidney. And, he adds, transplanting HIV-positive people with organs from HIV-positive donors would free up other livers and kidneys, from HIV-negative donors, for people who aren’t living with HIV.

The ban went into effect with passage of the Federal National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, according to the HIVMA. Back then, no transplant program would accept HIV-positive individuals as organ recipients, let alone donors (though there was never a formal prohibition on recipients). Because HIV infection was considered a death sentence in those years, transplanting an organ to a person living with the virus was regarded as a waste of the organ.

“At the time [the Transplant Act] was written, it was appropriate,” Segev says of the ban. “Now, it’s incredibly antiquated. This law is about as modern as making copies of music for somebody on an audio tape.”

Even as antiretroviral drugs began extending the lives of people with HIV, few transplant centers would accept them to receive new organs. That’s because transplant recipients must take immune-suppressing medication to prevent their immune system from rejecting the donated organ; doctors feared these drugs (which in some cases must be taken for life) could accelerate the recipients’ HIV and leave them susceptible to opportunistic infections.

But the only way transplant centers could know for sure whether anti-rejection drugs would worsen people’s HIV was to test the theory by actually transplanting some positive recipients (with organs from negative donors), a step some centers took in the late 1990s, believing it could be done safely. They chose carefully, focusing on recipients whose HIV was well controlled with medication.

Their gamble paid off. “It’s been shown repeatedly that we don’t really have a big problem with HIV [viral load erupting] after transplant,” says Christopher Hughes, MD, surgical director of liver transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh’s Starzl Transplant Institute. Not only did people’s viral loads stay stable, but their immune systems did too: HIV-positive transplant recipients didn’t come down with dramatic opportunistic infections as had been feared.

Today, at least 21 transplant centers in the United States provide transplants of organs from HIV-negative donors to HIV-positive recipients, although the ban on positive donors means there is no experience of transplanting from one positive person to another. In South Africa, however, surgeons have transplanted several organs from HIV-positive donors, with excellent results.

Once the ban against HIV-positive donors is lifted, surgeons will need to proceed just as cautiously as they did with HIV-positive recipients, says Hughes, who has transplanted about 14 such recipients over the years. “One concern is that the donor might have a more aggressive HIV subtype than the recipient,” he says. “I think we need to make as sure as we can that the donors’ HIV was treatable during their lifetime.”

And, Hughes says, strict safeguards are needed to ensure that an organ from an HIV-positive donor isn’t transplanted into a recipient who doesn’t have HIV.

Segev calls such mislabeling “probably a very minor concern.” After all, he says, rapid tests are available, and “we use hepatitis C–infected organs all the time.” To his knowledge, he says, there have been very few cases in which one of them was transplanted into someone who wasn’t living with that virus. He adds some context: “Death rates for people on the [organ transplant] waiting list can be anywhere from 5 percent to 50 percent a year.”

Given that an estimated 30 percent of people living with HIV have hepatitis C and that 10 percent of positive people have hepatitis B, it seems likely that HIV-positive people will continue to crowd waiting lists for liver transplants. And as people with HIV keep growing older, they could require transplants of other organs as well—especially kidneys, because of HIV-related kidney disease.

Meanwhile, Tripp and Sherbert are forced to await the call that a liver from an HIV-negative donor has become available. They moved last September from California to Jacksonville, Florida, where the Mayo Clinic’s transplant program promised a shorter wait than others—a detail Tripp picked up from searching the United Network for Organ Sharing website, UNOS.org. In his experience in Jacksonville, Tripp says, most transplant-seekers on the list wait from three to six months.

When the couple arrived in Florida, Sherbert was in a wheelchair and “constantly sick,” Tripp says. But his health has since stabilized. Significantly, his CD4 count has risen to the high 120s—clearing the level required for liver transplant recipients: 100 CD4s. (Kidney recipients must top 200 CD4 cells.)

“The transplant should have been done years ago,” Tripp says, “and we could both have been back to work leading productive lives. Instead, we must rely on government systems to support us. It is just unnecessary.”

Sherbert agrees, calling the ban the only obstacle. “I have no problem accepting an HIV-positive liver,” he says. “I would love to be transplanted and start the healing process and go back to work and have a normal life again.”

Get Involved

Help get the ban on HIV-positive organ donation lifted

To help convince Congress to abolish the prohibition, the HIV Medicine Association is collecting examples of people who would benefit if the ban on transplanting organs from HIV-positive donors were lifted. If you or someone you know is HIV positive and waiting for an organ transplant, email your story and your contact information to the HIVMA’s Kimberly Crump at policy@hivma.org. Even if you don’t know anyone who’s affected by the ban, you can contact your congressional representatives and urge them to repeal it.

You can find how to reach your U.S. senators and representatives at contactingthecongress.org.

Sign up to be an organ donor

If you have HIV, signing up to be an organ donor would be “a brilliant demonstration” that you’re truly committed to becoming one, says Johns Hopkins transplant surgeon Dorry Segev, MD.

To sign up online, visit organdonor.gov/becomingdonor/stateregistries.html and click on your state on the map. That will take you to a page with sign-up forms for your state—some can be submitted online; others must be downloaded, signed and mailed in.

Also, next time you renew your driver’s license, you can indicate you’d like to be an organ donor. Tell family and friends of your wishes and include that information in your advance directives, will and living will. And don’t stop there: Ask others to sign up too.

Find more information on organ transplants for positive people at hivtransplant.com.

3 Comments

3 Comments