Even before the forum “Challenging the Culture of Disease” began on a chilly night last November at New York City’s gay community center, something extraordinary was clearly happening. The overflow crowd of 300 had lined up for hours to weigh in on the question asked by the promotional posters, “Why are new infections increasing among gay men again?” A 60 Minutes camera crew was there, filming a segment on the evening’s moderator, playwright Harvey Fierstein—longtime gay activist, AIDS fundraiser and drag star of the Broadway smash Hairspray. “When people looked around and realized this many of us were concerned,” recalls HIV positive gay psychotherapist Michael Shernoff, a “palpable electricity” raced through the room.

What could so excite a veteran like Shernoff, who had seen many such crowded debates spark and fizzle since the days of ACT UP? Partly, it was Fierstein’s star power—in July 2003, he’d written a much-discussed New York Times op-ed, charging HIV-drug ads and the gay community itself with having normalized, even glamorized, AIDS. Still, the turnout was a surprise, particularly because the forum had been organized by two HIV negative guys with few ties to the AIDS establishment: Dan Carlson, a freelance PR man, and Bruce Kellerhouse, a psychologist.

Fierstein’s gravelly, Bea Arthur voice started the hoo-ha on a campy note: “We gotta solve the world in two hours—so fix your makeup.” But that’s where the humor ended. Panelist and community doctor David Kim, MD, reported that New York City gay men had experienced a 17 percent spike in HIV infections over the past three years—as well as a syphilis epidemic. Dennis DeLeon, longtime HIVer and head of the Latino Commission on AIDS, observed that HIV rates were even higher among gay men of color and wondered “why this city has failed us” in prevention leadership. Michael Roberson from People of Color in Crisis told the predominantly white, over-35 crowd, “I’m here because black gay men are afraid to be here.”

The open-mic session ranged from the feisty to the ridiculous. “Who started the rumor that raw sex was masculine sex?” demanded one middle-aged man, lamenting that “few people care what HIV negative people like me have done to stay sexually active—and negative.” “You don’t know what it was like to be HIV positive in the ’80s,” a longtime PWA harangued. “It was a horror.” Another man fumed that he had seen “people with KS lesions barebacking twentysomething twinks in sex clubs” and that HIV had become “a badge of honor.” A twentysomething said more of his peers would have shown up if Britney Spears had moderated. (“I’ll be sure to tell Britney tonight when I get home,” Fierstein quipped, bringing down the house.)

Amid the conflicts and contradictions, one panelist couldn’t be ignored: former ACT UP luminary Peter Staley. Staley’s confession that he was recovering from crystal-meth addiction, which had led him to unprotected sex without discussing his HIV status, stunned the crowd—and revealed the elephant in the room. “Crystal is fueling most of the unsafe, binge-style sex and multiple HIV exposures,” Staley said, adding, “GMHC should be screaming about this.” (For more on the crystal crisis, see POZ’s July/August 2002 story “Life Vs. Meth.”)

Staley’s biggest moment came toward the end of the forum, when a PWA, showing signs of wasting, expressed dismay over San Francisco’s graphic hiv is no picnic poster campaign depicting med side effects like “protease paunch” and diarrhea. “When you attack the disease,” he said, “you are attacking the people who have it.”

Staley shot back, nearly leaping from the dais: “How do we say to our HIV negative brothers that [having HIV] is hard without saying it’s bad in some way? I think we gotta live with the truth here. [HIV] is not something people should get.” The room fell silent: This was un-PC tough love from a veteran that perhaps they weren’t ready to hear.

DeLeon called the evening a “remarkable” turning point, when honest talk about responsible choices overcame gay men’s long-defended cult of sexual liberation: “Suddenly, the community is past the fear that someone is going to take away their sex.”

AIDS activism may have been born in New York City in the mid-’80s, but since the mid-’90s, Gotham’s grassroots militancy has been missing in action. Even as treatment advocates (many of them HIVers) have secured a place at the table, activism around prevention is sputtering toward extinction—just when New York City could be on the brink of another epidemic. While experts have for years cited a familiar litany of causes for the steadily rising rate of gay infections, including condom fatigue and the new view of AIDS as manageable by HAART, no one doubts the role of methamphetamine, known as crystal. In January, the gay-serving Callen-Lorde Community Health Center said two-thirds of those testing positive for HIV since June 2003 had cited crystal meth as a factor.

Although such West Coast cities as San Francisco, Seattle and Los Angeles sounded the alarm about the HIV-crystal connection several years ago—and their health officials and AIDS groups responded (see “Meth Traps”)—New York City’s HIV honchos have been reticent. The stalwart Gay Men’s Health Crisis has produced no groundbreaking gay prevention since such campaigns as “Staying Negative—It’s Not Automatic” nearly a decade ago. The city’s health department has done even less. November’s forum, however, triggered a chain of prevention events throughout the city’s long, cold winter of 2003–4. Staley put up $6,000 of his own money to mount eye-catching posters on Chelsea’s Eighth Avenue (the heart of the gay ghetto) picturing a shirtless hottie with a mirror-ball head beside the text huge sale! buy crystal, get hiv free! GMHC’s executive director, Ana Oliveira, answered with a crystal-meth task force and a “crystal can lead to HIV” print campaign, urging users to visit its Substance Use Counseling and Education Program. A second, larger forum in February, again hosted by Fierstein, homed in on “The Crystal Meth–HIV Connection,” featuring a rep from the city health department. In late March, gay city council members Phil Reed (who’s HIV positive), Margarita Lopez and Christine Quinn convened with Staley and other activists on the City Hall steps to protest the zero dollars earmarked for educating gay New Yorkers about crystal—that same day, assistant health commissioner for HIV/AIDS Marjorie Hill told POZ that the health department had found $300,000 for that purpose.

A flurry of boldface names—Fierstein, Staley, Oliveira, Reed—were now linked to this new wave of crystal activism, but it was Carlson and Kellerhouse who emerged as stars, two fresh faces everyone suddenly wanted to have lunch with. The mild-mannered, buttoned-down duo is as far from the shaven-headed, combat-booted, fist-in-the-air faggot (or die-hard dyke) of high-’80s ACT UP as you can imagine—the perfect facilitators for a new post-protease, post–Will and Grace, post-9/11 gay activism—and their sudden rise has raised questions aplenty. Some are admiring: Where did they get the idea for these community gabfests? How, facing paralyzing complacency, did they succeed? How did they capture an old hand like Staley—who “no longer considered [himself] an activist”—and his trademark frankness and genius for publicity? Others are skeptical: Where do these new leaders want to take us? What are they getting out of it? Already, Carlson and Kellerhouse are tangled in controversy over how much they’re pocketing to produce the forums, putting them at odds with their very own celebrity, Harvey Fierstein.

As the epidemic raged in the late ’80s and early ’90s, there was no greater hero than Staley, now 43, diagnosed with HIV in 1985. He impressed the fledgling ACT UP in 1987 as one of the first members to disclose his status not only to the floor, but to the media. It didn’t hurt that he was fiercely articulate and boyishly mediagenic. He soon became one of the prime players in getting the government to fast-track HIV-drug development and approval. Then, he and other treatment elites split to form the Treatment Action Group, which canoodled with the health honchos of the early Clinton administration.

Then came HAART, and Staley realized that he would live longer than planned: “I spent two years trying to figure out what to do with my future,” he says, “living on disability and annual gifts from Mom and Dad, and I resigned myself very quickly that what had occurred in the ACT UP years was unrepeatable.” He founded www.AIDSmeds.com, a website devoted to treatment ABCs for everyday HIVers, which he calls “very successful—we have close to 300,000 visits a month.”

Career crisis resolved, he entered a midife crisis. “I was about to become 40, wanting to feel young, attractive, sexy.” He discovered crystal meth in 2000 and “knew I was addicted after my third binge.” Attempts to control his use via therapy failed, and during binges he would have unprotected sex without discussing his or his partners’ HIV status. “I was on antivirals and undetectable, so a case could be made that I didn’t infect anybody.” He curtailed the practice when an HIVer friend told him bluntly, “That’s not good.” After that, he says, “I’d be one of the few in the crystal-meth underground that would proactively disclose,” both in his website profile and in person. To what effect? “Usually shock,” he says with a laugh. Of the men he might have exposed to HIV, he says he feels “shame—which I’ve dealt with through a lot of counseling.”

Finally, thanks to a 12-step group and intensive outpatient group therapy, he got clean and says he’s been crystal-clear since November 2002, mainly because “I talk to people every day,” he says, adding, “The urges have abated but I have a feeling I’ll never stop missing it.”

Kellerhouse knew getting a crystal-savvy AIDS veteran like Staley was “crucial” for the first HIV forum, and his timing was perfect. When he and Carlson came calling, Staley was a few months free of crystal and itching to interrupt the gay community’s silence around the drug. Though he says his “full-time activist” days are over, Staley is proud to be a part of “the birth of crystal-meth activism in New York. Making crystal the focus is a great way to allow a broader discussion so everything gets some attention.”

He adds, “Nobody’s working harder these days on HIV prevention than Dan and Bruce.”

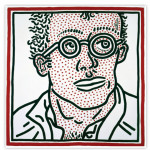

Double Trouble: Staley shattered New York complacency last winter--and nearly two decades ago, as one of ACT UP’s first public HIVers.Dean Kaufman

“I had no idea that at 50 I’d become an AIDS activist,” says soft-spoken psychologist Bruce Kellerhouse, PhD, who has run therapy groups for HIV positive and negative men. Such a career also seems unlikely for his friend of nine years, Daniel Carlson, 34, who has done PR for HIV meds like Fuzeon—and whose blond, blue-eyed good looks belie a tenacity that has made these two synonymous with HIV Forum, a name they conceived for that Sunday-night summit.

Any self-respecting handcuffs-loving ACT UPer listening in as Carlson and Kellerhouse spoke to POZ at a diner in Chelsea—the heart of the hard-partying crystal lifestyle—would likely be put off by their measured therapy-speak and Banana Republic blandness. But the two men’s friendship embodies the communication and caring—passing survival skills from one generation to the next—that they hope to inspire in other gay men. Raised in upstate New York, Kellerhouse moved to New York City after college in 1976, what he calls a “fantastic” time for gays in the city—“being free, being part of a community. We were total discophiles.” But fantastic morphed into the “horrific” AIDS era, killing his lover and 20 to 30 friends. He remained HIV negative (“I may have had sex with 25 people”), but by 1989, with so many missing peers, “I didn’t feel I was part of the gay community anymore”—ironically, the moment others were filling the streets to rage against AIDS. He quit a high-paying job to pursue his doctorate in psychology at New York University, in part because he’d had a “powerful therapy experience” working through his losses. Kellerhouse says his Forum work springs from his experience designing “health and wellness programs.”

At NYU, he met Carlson, a South Dakota native getting his masters in media ecology and getting in touch with his gay self. “I went to Bruce and said, ‘I may be gay,’” Carlson says. “He was like an angel to me.” Kellerhouse remembers “a freshness, an unspoiledness about Dan”; he helped Carlson cope with his anxieties about HIV and sex, including ways to ask sex partners about their HIV status.

Despite his caring mentor, Carlson drifted into the usual byways of urban gay life—drinking, drugging, unsafe-sex slipups. A self-described alcoholic, Carlson, like Staley, joined a 12-step program and says he has been clean and sober for the past 15 months and recently tested negative. He adds that once he had kicked booze and drugs, he noticed with new clarity “that more guys wanted to have unsafe sex with me. They’d say things like, ‘Well, you can blow me or I can come down your throat.’ Some, but not all, were high. I had safe sex high on crystal myself.” Over discussions with Kellerhouse, Carlson realized that he wanted support from the gay community for his desire to stay negative, but got none. This desire, more than anything else, may be why the forums exist. Asked to elaborate, Carlson hesitates, glancing at his friend. “It’s the fear,” he says. “Not just of potential health consequences—but on a personal level, I would feel a sense of failure. I would feel anger. I don’t generally pursue relations with positive people because I have a lot of fear—I would feel a lot shame if I got it. I have people’s voices in my head: ‘With everything you know—you should know better.’”

“HIV is scary to talk about,” Kellerhouse breaks in. “It’s loaded—with shame, rejection, guilt. Negative guys are so afraid of hurting positive guys. And for positive guys, the main fear is rejection. We need to work through the shame of HIV and other barriers we have to telling the truth.” They hoped to begin to smash those barriers when they conceived their first event. “Finally, we said, ‘Nobody’s talking about it. Let’s try to organize a public forum,’” says Carlson. The two had admired Fierstein’s Times op-ed and convinced him to moderate; then, with a signed letter from the star in hand, they went up and down Chelsea’s Eighth Avenue asking the gay-serving, often gay-owned shops and cafés for money to foot the event. Only one—Gerry’s Menswear—kicked in, but a mass e-mail plea to friends and a donation from Astor Medical Group brought the $1,900 they say they needed to produce the event.

Their reaction to the chain of events that followed the first forum is typically low-key. “We upset the apple cart a little bit [that night],” Kellerhouse says. What they didn’t intend was to upset Fierstein.

While Fierstein’s face will forever be associated with the first two forums, many people don’t know that Broadway’s beloved drag artist parted with Carlson and Kellerhouse after their second event, in early February. Fierstein told POZ that he’d learned that the duo had received not only $15,000 from Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS to operate the forums but an undisclosed sum from gay philanthropist Henry van Ameringen to pay themselves a stipend. Fierstein says that when he asked them how much money they got, “I was basically told to mind my own business. I asked, ‘Are you thinking of creating another [AIDS] organization’ which in my mind the world doesn’t need, and they said, ‘Not now, but we may.’”

Fierstein also questions the accountability of these newly minted community leaders—an issue he was the first to raise but one that seems inevitable. “All of a sudden Dan Carlson is putting himself out there as an AIDS expert? Bruce’s speech at the [crystal] forum was so boring, I was shocked he opened his mouth,” Fierstein says. “If you’re going to use my name, face and reputation to raise money and then pay yourself without even telling me, something is really wrong,” he says.

Carlson initially refused to quantify their stipend for POZ, saying only that it was offered, not asked for; modest by New York living standards; and that they couldn’t continue their forum work and support themselves without assistance. “It takes a ton of time to pull this stuff together,” Carlson says. “As far as forming an organization, we have no application pending for nonprofit status; we’re [financially] accountable to Callen-Lorde [where HIV Forum has an office]; and we have no plan past October. We only wanted to do one forum, but the response was so incredible. Bruce and I do not take a day off.”

But after van Ameringen told POZ he’d given the men a lump sum of $45,000, they broke it down: $30,000 from January to June 2004 for Carlson, who works on the project full time, and $15,000 for Kellerhouse, who maintains his therapy practice. In a written statement, Kellerhouse said they withheld the amount from Fierstein because they found his inquiry “surprising,” because “his request for such intimate details…implied greater collaboration than what actually existed.” By phone, Kellerhouse said he and Carlson would “always be grateful to [Fierstein] for the important role he played” but that Carlson was “saddened…that [Fierstein] feels the need to devalue and sully something that is so…beneficial to the community.”

The funders stand by Carlson. “I’m so discouraged about AIDS prevention I’m willing to give anyone a hearing and money,” van Ameringen says. “I think what they’re doing is worth a try.” Tom Viola, head of Broadway Cares, calls the first forum “terrific” and hints at giving more money: “I understand the altruistic idea that all this work should be done for nothing, but [in my own experience as a fundraiser] it costs money to raise money.”

Staley agrees: “When I left Wall Street and became a full-time AIDS activist, I relied on my family [financially]. Dan and Bruce need to pay their rent as much as anyone.” He calls Fierstein’s defection a “non-story,” noting “the [AIDS activist] movement has an unfortunate history of infighting.” And a well-known prevention researcher who declined to be named sent this message to Fierstein: “Fucking grow up.”

Carlson and Kellerhouse’s agenda for the HIV Forum remains as ambiguous as their financial accountability (learn more about the group at www.hivforumnyc.org). “Our intention was to have one forum, to get people talking,” says Carlson. He adds that they “didn’t intend” their HIV Forum to outgrow the shingle they hung to hawk the event. Despite their success, the two haven’t stated formal positions on how to promote prevention, how to control crystal or any other of the knotty issues central to the crisis. For now, they’re content to force issues with expert-guided talk, and whatever action results is gravy, beyond their control. Of the immediate future Kellerhouse says only, “We need to sit down and make a plan within the next 30 days.” He won’t rule out going nonprofit, but insists that “the important thing for us is to maintain our grassroots nature, which permits us to be quick to respond to the community’s needs.”

The Fierstein flap suggests that the duo should tread carefully. “They play it very close to the chest, and if they’re doing that with me, it’s not very good,” says van Ameringen. Viola says, “I’m not interested in funding a nonprofit for what can very easily be done” through the infrastructure of another group, such as Callen-Lorde, the duo’s current custodian.

Community leaders must endure all kinds of criticism, valid or not. Besides the Fierstein affair, myriad other critiques of HIV Forum have arisen. Some say the first event’s freewheeling community fervor vanished in the second one, a dry panel of medical and public-health experts, somewhat relieved by more confessions from Staley and a younger recovering crystal addict, newly diagnosed with HIV. The third forum, “Crystal Meth and the Law,” included, rather incongruously, a self-described “enraged” Allan Clear from the robustly anti-narc squad Harm Reduction Coalition. The new moderator, the editor of Gay City News, held a looser rein on the crowd, making for a lively evening of hostile volleys aimed at the increasingly defensive law-and-order brass. But many people left baffled by the event’s purpose.

What’s more, HIV Forum events have attracted primarily the white and the over-35. Roberson, of People of Color in Crisis, wishes Carlson and Kellerhouse “had reached out to us a little earlier, asking other community-based organizations to bring folks. A lot of black people perceive [the gay community center] as a white agency.” Carlson and Kellerhouse are considering working with Harlem ASOs to host a forum there in the fall, though Carlson says, “I don’t even know if I’m the right messenger—a blond, blue-eyed white guy.”

And a busy one. He and Kellerhouse are organizing another major forum slated for mid-May (likely a “Can We Talk?”–style face-off for negative and positive gay men); a fall event targeting gay men under 30; and perhaps one or two smaller, more quickly arranged events, because “we do like to be nimble.” Can such big-scale talk therapy produce a community breakthrough powerful enough to halt rising infections in an age of Internet hookups, crystal binges and the belief that HIV is just another STD? DeLeon, who for two decades has survived HIV and the challenges of being a community leader, says the forums have made it “chic to be responsible now, and I hope it continues, because these moments have a shelf life.”

Comments

Comments